|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | April 2005 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | April 2005

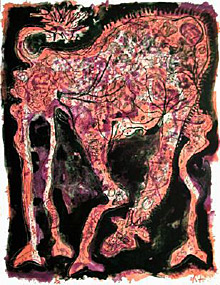

The Mad Menagerie of Rodolfo Nieto

John Maxim - The Herald Mexico John Maxim - The Herald Mexico

| | An exhibition of the drawings and graphic art of Oaxacan artist, Rodolfo Nieto, celebrating the 20th anniversary of his death, is on show at the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City. |

Outstanding Mexican painter Rodolfo Nieto was born in Oaxaca July 14, 1936, and spent the first dozen years of his life there, until his family moved to Mexico City in 1949. His artistic vocation led him to enter the Esmeralda School of Art in 1953 at the age of 17. During the 1950s, painter Juan Soriano became his artistic mentor and introduced him to various painting media. More importantly, he instilled in the young artist an appreciation for European art.

Nieto was particularly drawn to German expressionism, according to author Alberto Blanco, and although they were not formally his teachers, Jesus Reyes Ferreira and Manuel Rodríguez Lozano guided Nieto during his formative years in the direction his art would eventually take when he matured. His first oneman show was in 1959 at the San Carlos Academy and was called "Steel, Blood and Killing," reflecting one of the brief occasions when Nieto's socio-political themes took precedence over his whimsey.

After that first exhibition, Nieto went to Europe and settled in Paris in 1959 to join the search for his particular path in modern art and to enter the ranks of great artistic searchers, from Picasso to Jean Debuffet and Paul Klee, whom he greatly admired. He made friends with authors, including Octavio Paz, and many painters, and travelled all over Europe absorbing the latest artistic trends while studying the great old masters in museums. He attended the lithograph workshop of Michel Casse and studied metal engraving with William Hayter.

By 1961, Nieto was exhibiting his works at the Modern Museum of Art in Oslo, Norway, home of the great expressionist, Munch, whose "The Scream" is one of the world's best-known works of expressionist art. At that exhibition, he shared the walls with another painter from Oaxaca who was just starting to be known, Francisco Toledo. Another great Oaxacan painter, Rodolfo Morales, a master of magic mytho-realism, was also just beginning his career. In 1963 and 1968, Nieto won top prizes at the Paris Biennial. He spent the entire decade of the 1960s in Europe, producing what would become the major and most important part of his prolific lifetime of works.

By the time he returned to Mexico and Oaxaca in 1972, he was famous. He began experimenting in various new media and techniques, including collages and lacquers, and began creating his bestiary, a series of playful, brilliant works of animals both real and mythological, which are among the most successful of his works. They contain a great sense of ironic humor, which he considered essential to artistic creation. He had many more exhibitions and won many more awards before his death in 1985 at 49 in Oaxaca.

This tribute to a fine Mexican artist, sponsored by the National Institute of Fine Arts and the National Council for Culture and the Arts, and curated and coordinated by Marina Vázquez Ramos, is presented chronologically, starting with pencil drawings from 1954 in which Nieto's originality and imagination are already evident.

There are crude figurative and abstract drawings with crayons, inks and gouaches on paper and lots of odd faces in which the beginning of a painterly style can be seen emerging. The first figurative drawings in pencil and ink on paper such as "El Carmen" are amusing, ugly little cartoons, while his little black cats in ink on paper are full of the artist's striking sense of observation. So are his untitled representational vultures, turkeys and birds, that we can see evolving into totally abstract versions of them.

His series of animals are especially good. "Horse" (1958) is full of bright blues, yellows and shocking pinks that show the influence of Picasso's horse in the "Guernica" mural, but that does not fall into typical Mexican folkloricism. On the contrary, it both expresses and makes fun of it. His colored inks on paper are particularly vivid with demented visions that raise all sorts of questions as to what Nieto was trying to express in his painterly trances. One suspects that tequila or mezcal may have been instrumental to his inspiration, although his intuition and subconscious are always under artistic control.

His 1966 "Spirographs," all in colored pencil, his 1967 series of "Serpents" and his frog-like "Basileo" use geometric forms bent to serve his purposes, and his mandrills, giraffes, cobras and endlessly fascinating and fabulous invented abstract creatures are dynamic and unleash subconscious reactions in viewers. They become rather like Rorschach tests that one must take to convince oneself that it's not one, but the painter, who was mad.

Controlled madness, as Kafka, Joyce and Nabokov proved in literature, has its own logic. But there is nothing wrong with being rather mad, especially via artistic creation, in this insane world, is there? Most people hide their madness; hugely talented and courageous Nieto just let it all hang out as he tread the tightrope between sanity and insanity. Walking through this exciting exhibition is a bit exhausting, because Nieto takes us on a tour of his tormented inner life. It's like walking through a minefield. Explosions occur.

His richly hued and elegantly drawn camels, elephants, toucans and zebras are really gorgeous, clever and compelling works in serigraphs, collages and mixed media techniques that show the artist's never-ending ability to reinvent himself. He even used a bit of Jackson Pollock's drip-drop-slop technique with great restraint and enjoyment, but it's so cleanly integrated into certain works that it's almost impossible to notice. The joy and the drama they contain are universal and contagious, because his painterly language speaks directly to each of us in different ways. He gets us at the gut reaction level.

This rare exhibition of the drawings and graphic works, including engravings and lithographs, of Rodolfo Nieto was made possible through the courtesy of his family, particularly Martha Guillermoprieto and Ignacio Saucedo Labastida and his wife.

UNESCO Lifetime Achievement award winning journalist John Maxim writes regularly on Mexico’s cultural scene for The Herald. |

| |

|