|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | August 2005 Entertainment | Books | August 2005

Anthology Captures Indigenous Voices

El Universal El Universal

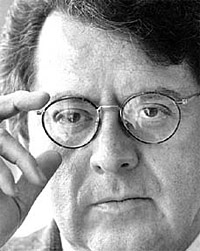

| | "Palabras de los Seres Verdaderos" is co-authored by award-winning Mexican writer Carlos Montemayor. |

In celebration of an ongoing resurgence of indigenous literature comes a monumental new, three-volume anthology that brings together a leading generation of its authors.

Entitled "Palabras de los Seres Verdaderos" ("Words of the True Peoples"), the anthology aims to give a broader audience to indigenous authors now seeking to reclaim their non-Hispanic cultural heritage. The volumes include works ranging from poems to theater, and each remains in its original language, along with Spanish and English translations.

More than a dozen languages including Maya, Zapotec, Nahuatl, Tojolabal and Huichol are included, and the anthology features biographies and photos of its authors by renowned cultural photographer George O. Jackson Jr. Co-authored by award-winning Mexican writer Carlos Montemayor and Donald Frischmann, a professor of Spanish and Latin American Studies at Texas Christian University, it also contains footnotes, glossaries and appendices consisting of essays on the cultural, religious and symbolic references found in the texts.

"With these new writers," Montemayor explains in the introduction to the first volume, "we have the possibility for the first time of discovering, through the indigenous groups' own representatives, the natural, intimate, and profound face of a Mexico that is still unknown to us."

And while there are not many overt political references in the stories, "the fact that these writers are writing in their maternal language and seeking publication in their maternal language," said Frischmann, "is an intensely political act in today's Mexico, in which there is great pressure to assimilate and almost exclusively adopt Spanish."

Though the anthology arrives in the midst of a resurgence of indigenous writing, he adds, unless there is "broad access to that literature, through linguistic bridges, such as the ones we've built, then the rest of the world only has an academic, or theoretical knowledge, of the existence of those writers and their works."

In fact, when he and Montemayor set out to gather writers for the anthology five years ago, they were struck with an overabundance of material. Since the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' voyage in 1992, explains Frischmann, there had been a debate among Latin American intellectuals and indigenous people over whether to celebrate the introduction of the Spanish language to Mexico.

This mood gave way to increased literary production, as well as a heightened awareness of the value of indigenous languages. (At the time of the Spanish Conquest there were an estimated 120 languages in Mexico. Today there are about 62, many of which have less than 5,000 speakers.)

Indigenous people, teachers in particular, said Frischmann, were "taking up the pen themselves in order to pioneer a movement of writing, and this happened many times independently in different parts of the country."

Frischmann and Montemayor decided to present writers who had decades of experience as educators, as well as a commitment to promoting their language and culture. Many of the authors included have appeared in print, on the local, regional or national level yet very few are women.

"We tried to include as many women writers as possible but there really weren't very many," said Frischmann, who is also a researcher at the Universidad de las Américas-Puebla. Although, with many fledgling indigenous women writers today, he added, "in a future work of this kind, there certainly will be a larger number of women writers available."

Published by the University of Texas Press, the recently issued first volume brings together 15 authors of stories and essays. The second volume, devoted to poems, is expected in October, and the third, covering theater, is expected in the fall of 2006. Throughout the works, the writers employ similar ideas and styles.

For example, there are a number of socalled guardians of nature, which assume different identities and names in different cultures, and who can be positive or negative forces depending on human behavior. Also, many of the stories read like folk tales, with characters that undergo trials resulting in a moral or lesson. And often, children are employed as narrators.

In one of the stories, a young boy reflects on his vision of the world.

As he relates ideas of the earth, his ancestors, and the deities of nature, the boy often returns to the phrase, "My grandfather tells me…" This narrative use of repetition in the story by Huichol writer Gabriel Pacheco mirrors a device used by traditional priests, explains Frischmann.

"Within the Huichol culture, it corresponds to the cultural repetition that would take place during religious ceremonies as carried out by traditional Huichol priests," he said. So, "the literary structure of the story is actually influenced directly by native, ritual discourse structures."

Perhaps the greatest personal lesson to be gained from the authors, said Frischmann, is their strong regard for nature.

"For the indigenous language writer the world is a living thing" in which "earth itself as a mother allows us to use her to produce food" and "mountains tower over and protect villages and towns below."

In a story by Tojolabal writer María Roselia Jiménez once president of the Mayas-Zoques Writers Group, Inc. and now coordinator of the Tojolabal Cultural Center in Chiapas she tells of a group of elder men who stop working in a field to visit a mountain.

They soon return with an abundance of cold fruit, which they share with their fellow laborers. Wanting to know where the elders found the fruit, the others one day follow the elders to a mountain called Ixk'inib, but find nothing. Later, they learn that the fruit came from their grandfathers, who live inside the mountain and are constantly playing music and dancing. "The mountain is there, keeping the Tojolabal town of Lomantam company, and preserving the memory of our grandfathers deep inside," writes Jiménez, who is pictured with the mountain in the anthology. "It takes just two hours to climb to the peak … Along the way, the hiker encounters exuberant vegetation and a cool flowing stream."

Unlike Western civilization, said Frischmann, the indigenous people have been faithful guardians of nature. "If we were to rectify our behavior to the world around us," he warns, "we just might be able to survive."

mahabir_karen@yahoo.com |

| |

|