|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | November 2005 Entertainment | Books | November 2005

Jesus Wept

Melvin Jules Bukiet - Washington Post Melvin Jules Bukiet - Washington Post

| | After years interviewing her vampires, Anne Rice sticks her neck out for the Lord. |

God - in the singular or plural, as deity or idea - has always been a great subject. From the Bible onward, a host of serious writers including Dante, Milton and Dostoyevsky has wrestled with divinity. More recently, there are so many examples that, in the words of St. John, "I suppose that even the world itself could not contain them."

God has figured in a modern version of midrash (a Jewish term for tale-spinning extrapolated from biblical text) by Jenny Diski, who retold the story of Abraham and Sarah in Only Human, and by David Maine, who retold the story of Noah last year in The Preservationist and that of Adam and Eve in this season's Fallen . Among the renderings of Jesus have been Jim Crace's sensuous isolate in Quarantine and Norman Mailer's ecstatic bombaster in The Gospel According to the Son.

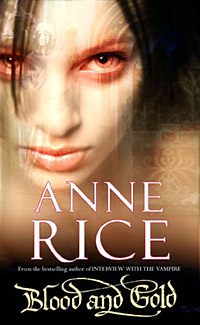

Now, say you had to guess the living writer least likely to feel compelled to enter this quest. How about Anne Rice? Known for multi-volume sagas of vampire lore and quasi-literary erotica, Rice has found religion in her new novel, Christ the Lord . On the surface ridiculous, this odd pairing actually makes sense if you consider the vampire Lestat and Jesus as flip sides of the same coin. Both are suffering young men who exist eternally, one by taking life, the other by giving it. And blood figures prominently in their stories.

The notion of Jesus a la Rice has a lot of appeal, especially after reading the first page of her previous book, Blood Canticle , which promises the lures she has reliably provided throughout her career: "a full-dress story . . . with a beginning, middle and end . . . plot, character, suspense, the works." Well, she may deliver elsewhere but not here; these niceties of narrative are uniformly missing from Christ the Lord .

As for the plot, it's a year in the life of a rather plodding 7-year-old boy. As for suspense, he discovers that several mysterious events attended his birth, but we already know that, and so do all the other characters, who are made entirely of cardboard. Mary is innocent; Joseph steadfast; Mary's brother Cleopas laughs so continuously that he might as well be at a vaudeville show; and James, the savior's older brother, glowers throughout the book with big-time sibling rivalry.

Perhaps we could tolerate a one-dimensional cast as long as the narrator/protagonist came alive on the page, but Rice's childhood Jesus is a cipher at the center of the book. Of course, he's also a cipher in Scripture. Interpretations of his nature differ among the four canonical Gospels - priest, prophet, king or God - and his early years are virtually a blank slate except for a few tantalizing legends that tell how the young Jesus breathed life into clay birds and, more shocking, killed a local bully. Rice aims to explore this apocryphal domain, but her Jesus is like no other child, not merely because he's begotten by the Creator of the universe but because he shows hardly an ounce of spunk or curiosity. He never burns as either a child or an incipient deity.

Nor do the surroundings of this fabulous tale provide any greater reward. At the beginning of the book, Jesus's family leaves a sojourn in Egypt to enter into a tumultuous Judea. King Herod the elder has just died, and the population is stuck between contending Roman soldiers, rebels and pillaging bandits. But this potentially dynamic setting remains inert. Aiming for scrupulousness based on her self-described extensive research, Rice takes no imaginative leaps and refuses to offer any but the scantest of detail. For example, she describes Jerusalem's Holy Temple as "a building so big and so grand and so solid . . . a building stretching to the right and to the left" so that the reader sees effectively nothing. In fact, real research would have provided abundant imagery, from the billowing purple curtains that veiled the Holy of Holies to the zodiac symbols embroidered upon them.

Worse still, clumsy and outright ungrammatical prose infects every page. For instance, we're told, "Joseph and Mary were cousins themselves of each other, that meant happiness for both of them." Presumably aiming for the resounding echoes of biblical syntax, Rice is merely redundant, so much so that the 300-plus pages of this book feel infinitely longer. Here's a sample of dialogue. Mary says, "Think of all the signs. . . . Think of the night when the men from the East came." Then Joseph says, "Do you think anybody there has forgotten that? Do you think they've forgotten anything. . . . They'll remember the star. . . . They'll remember the men from the East," to which Mary replies, "Don't say it, please. . . . Please don't say those words."

Likewise, the consciousness of the Jesus who narrates is repetitive as well as uninformative. Meeting cousin Elizabeth for the first time, Jesus notes, "I thought her face pleasing in a way I couldn't put into words to myself." Then he describes himself as having "the mind of a child who had grown up sleeping in a room with men and women in that same room and in other rooms open to it, and sleeping in the open courtyard with the men and women in the heat of summer, and living always close with them, and hearing and seeing many things," none of which he shares with us.

Stunned into earnestness by a personal tragedy that she refers to in an afterword, Rice cannot summon any of the literary blood that throbbed through her multiple neck-biters. She strives diligently, but she's so respectful that no messy humanity whatsoever comes from her deity. Christ the Lord is more of an act of personal devotion than the fulfillment of an acknowledgedly audacious fictional concept. It will neither offend believers the way author Nikos Kazantzakis and director Martin Scorsese did in "The Last Temptation of Christ" nor satisfy evangelicals as did Mel Gibson's "The Passion of the Christ." Instead, both audiences are likely to be bored.

Whether Jesus was the soul of mercy or, as some historians have claimed, a political rabble-rouser, the one quality he must have had in order to live through the millennia was spirit. It's the one great quality the Bible has in abundance, as revealed by either the chiseled spareness of Everett Fox's translation of Genesis or the luscious oratory of King James. Rice has sucked the life out of the greatest story ever told.

Melvin Jules Bukiet's most recent book is the collection "A Faker's Dozen." He teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. |

| |

|