|

|

|

Entertainment | Restaurants & Dining | December 2005 Entertainment | Restaurants & Dining | December 2005

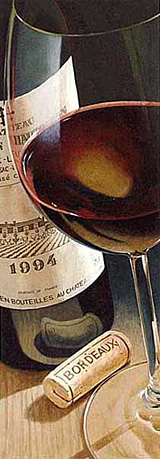

Message in a Bottle

Tom Standage - NYTimes Tom Standage - NYTimes

| | The Romans were the first to use wine as a finely calibrated social yardstick - and thus inaugurated centuries of wine snobbery. |

The question is simple enough: which wine will you serve on Christmas Day? But the answer is far from straightforward, for your choice of wine is laden with meaning. Is it from the Old or New World? Does it emphasize fruit over terroir? Did you have to put your name down on a boutique winery's exclusive waiting list to get hold of it? And, of greatest importance to many wine buffs, what score did Robert Parker, the world's most influential wine critic, give your chosen bottle on his famed 100-point scale?

Most of us don't worry like this about our choice of beer or coffee. But wine is the king of drinks and the drink of kings, unique in its association with status. A wine's rank is expected to correspond to both drinker and occasion: an inappropriate choice of wine reflects badly upon the host, and an apparently straightforward choice thus becomes a social minefield.

But do not blame Robert Parker; blame the Romans. The contemporary obsession with obscure California cabernets, arcane vocabulary and suspiciously precise numerical scales is merely the latest incarnation of a tradition with deep historical roots. Millenniums ago, in beer-drinking Egypt and Mesopotamia, scarcity and high cost limited the consumption of wine to the elite and made it a status symbol. But by the Roman period, production of wine had so increased that even slaves could drink it. That meant that simply drinking wine was no longer a sign of status, so distinctions among wines became far more important.

The Romans were the first to use wine as a finely calibrated social yardstick - and thus inaugurated centuries of wine snobbery. Drinkers at a Roman banquet might be served different wines depending on their positions in society. Pliny the Younger, writing in the late first century A.D., described a dinner at which the host and his friends were served fine wine, second-rate wine was served to other guests, and third-rate wine was served to former slaves.

Falernian, a wine grown in the Italian region of Campania, was generally agreed to be the finest wine of the Roman period. Mr. Parker's Roman predecessors decreed that its best vintage was that of 121 B.C.; it was served to the emperor Caligula in A.D. 39, though by then it was probably undrinkable. In the second century A.D., Galen of Pergamum, personal doctor to Emperor Marcus Aurelius, prescribed Falernian for medicinal use, on the ground that the finer the wine, the greater its curative properties. Descending into the imperial cellars, Galen tasted dozens of vintages to find the best. Which vintage he chose, and whether he rated the wines using a 100-point scale are, alas, not recorded.

Just how seriously the Romans took the business of wine classification can be seen from the story of Marcus Antonius, a Roman politician who in 87 B.C. found himself on the wrong side of a power struggle. He sought refuge in the house of an ally of much lower social rank. But his host unwittingly gave him away by sending his servant out to buy wine worthy of such a distinguished guest. When the servant asked for a far more expensive wine than usual, the wine merchant became suspicious and informed the authorities. Marcus Antonius was discovered and beheaded.

The close association between wine and sophistication in the ancient world contributed to its rejection by Muslims. With the rise of Islam in the seventh century, Mohammed's followers expressed their disdain for the previous ruling elites by replacing wheeled vehicles with camels, chairs and tables with cushions and by banning the consumption of wine. Being devout, they signaled, was more important than seeming sophisticated.

In Europe, however, the idea of a hierarchy of wines survived into the medieval period. In the "Battle of the Wines," a fictitious wine-tasting competition described in poems written in the 13th and 14th centuries, European wines were ranked by a priest. The top wine, from Cyprus, was declared the pope of wines; the second best was made a cardinal; lesser wines were declared kings, counts and peers. (Eight wines were deemed so bad that they were excommunicated.) It is but a small step to the five categories of the Bordeaux classification of 1855, and ultimately to the 100-point scale of today.

Yet the idea that wines can be ranked with scientific precision is absurd. Wine is not consumed in a vacuum. Try to recall your most memorable bottles, and you may find, as my wife and I did, that they were the humble bottles drunk while cooking on lazy holiday evenings, or the reliable glugging wines shared with friends and food. Wines brought back from vacation frequently taste revolting out of context; blockbuster wines put aside for a special occasion can fail to live up to expectations. Context matters just as much as the contents of the bottle.

So put not your faith in wine rankings imposed from on high by god-like critics. There are no right or wrong answers when it comes to wine; the only score that matters is your own taste. And the best bottles are often those served in a convivial atmosphere among family and friends - something that no ranking system, ancient or modern, can quantify.

Tom Standage, the technology editor of The Economist, is the author of "A History of the World in Six Glasses." |

| |

|