Mexico's True Colors

Susan Harb - Washington Post Susan Harb - Washington Post

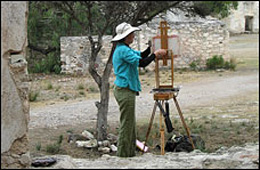

| | Eight Virginia-based artists traveled to the Mexican town of San Miguel, a 16th century town that draws artists from around the world intent on capturing its light, landscape and architecture. |

Tangerine. Pumpkin. Butternut squash. Dreamsicle. Apricot. Mango.

We were walking single-file down the narrow sidewalk of Calle de San Francisco in the heart of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico - eight Virginia artists, each weighing in on the precise color of the adobe walls of the colonial buildings that skirt the cobblestone thoroughfare.

Sweet potato puree. Cantaloupe. Peach chutney.

Not an orange in the bunch.

For two weeks last February, our small band of plein-air (open-air) painters skipped out on cold fingers and frozen tubes of acrylics for the vibrant warmth and visual charm of the 16th-century town, an established haven for American and Canadian expatriates about 170 miles north of Mexico City. We ranged in age from 42 to 70, and most of us lived in the Charlottesville area; some had met in art classes, some on other painting excursions. Our merry cortege joined the Sunday painters, degree-seeking students and established artists who pour into San Miguel for its luminous light - often compared to that of Tuscany and the Hamptons - and its plethora of art classes, tours and exhibitions.

"Somebody pinch me," said Anne War ren Holland, 60, from St. George, Va. The morning after our midnight arrival, she woke up in a 300-year-old villa, stepped out on the rooftop terrace and was nearly nose-to-nose with the baroque steeple of the Parroquia, the grand pink sandstone church that anchors El Jardin, San Miguel's main square.

Moments of elation occurred throughout our visit as we let the colors, textures and architecture of old Mexico embrace us. We were ourselves the blank canvases eager to be filled.

"I want to see it all, taste it all, paint it all," said Gray Dodson, 66, a landscape artist from Lovingston, Va., overwhelmed after her first walk to the market. "Where to start?"

We started early, getting up before 7 each day to peer at the sky and gulp coffee. Grabbing easels, paints, cameras, hats, water bottles, sunscreen and street maps, we headed out to catch the sun the moment it broke through the morning cloud cover and cast its rosy glow. Make that a midrange magenta glow.

We went back to the villa for breakfast at midmorning, then set out again, sometimes painting through lunch and siesta if the scene were seductive enough. If not, brushes were set aside for shopping and sightseeing.

We were major buyers in the artisan market that meanders for blocks - pantry-size booths spilling over with tinware, piñatas, pottery, bark paintings, weavings, crude handmade toys and fancy leather tooling. We were mainly browsers in the chichi Santa Fe-style clothing and home furnishings boutiques that proliferate behind handsome wooden doors and fashionably faded facades throughout the historic area.

By 5, it was back to business. Backpacks on wheels rolled down the street in a convoy, strategic viewpoints were established, paints uncapped, brushes poised before the azure, indigo, sapphire, denim, lapis, cobalt sky turned into a crimson sunset.

It was enough to make a serious painter swoon.

El Centro of Art

San Miguel has an authenticity that belies its large gringo presence. Founded on a hillside in 1542, designated a national monument in 1926 and now a city of nearly 100,000, its intimate, historic El Centro seems to be caught in a time warp. There are no stoplights, fire hydrants, neon, billboards, skateboarders or condos.

Mexican culture seeps from the old stone and terra cotta buildings. A former convent is an arts center; an ancestral villa houses the Instituto Allende, which cleverly opened its doors in the 1950s to students studying on the GI Bill and thus initiated the artistic pilgrimage that exists today.

The city smells old - earthy and dusty with a hint of burro dung, sweetened by the scent of geraniums or jasmine wafting over a garden wall. It sounds ancient. There are more than 20 Catholic churches, many with active bell towers that fill the air - morning, noon and all night - with a joyful, ancient cacophony.

Fireworks, festivals and parades are commonplace, as there is always something to celebrate - a saint's day, a wedding, a national holiday. The hurly-burly Mercado Ignacio Ramirez anchors the community's commerce, dispensing everyday essentials: fresh nopales paddles (edible cactus), pomegranate seeds, calla lilies, free-range chickens, garlic braids, sombreros.

The Jardin, shaded by flat-topped laurel trees and scrubbed every morning by a crew wielding buckets of soapy water and brooms, is San Miguel's outdoor theater and senior social center. Missing are the young waif jewelry-makers and dreadlocked musicians you see selling their wares and talents in other well-trafficked destinations. It's an older crowd.

Iron benches and lampposts give the park a European feel. You can get your shoes shined here, sign up for a walking tour, buy a bag of popcorn or the International Herald Tribune. On weekends, there are bands, and canoodling sweethearts and children can take a horsy ride . . . on a real horse.

And on every street corner, behind the many garden walls, in fountain-dancing courtyards, secluded alleys, jostling markets and terraced rooftops, there is an easel or a sketchbook or a camera and an artist absorbed in recording this storybook scene.

"Our task," said portrait artist Amy Varner, 49, of Charlottesville, painting in the Jardin early one morning, "is to put it all together and make these paintings images that are compelling universally, not postcard paintings."

Those cliche images attract an estimated 10,000 visitors to San Miguel annually; 5,000 North Americans live there full time. "It seems everyone in San Miguel is an artist," said Dawn Gaskill, a painter who moved there four years ago from Dallas and recently had an opening at the Dallas Museum of Art. "I would say that even if they don't personally have a creative endeavor, they choose to live their life creatively by moving here."

"The beauty of San Miguel alone is enough to awaken any dormant muses," said Patrice Wynne, a photographer from Berkeley who moved to San Miguel several years ago and is now a full-time resident.

It was hard to plant an easel on a street corner and not get a tourist in the picture.

On our forays about town, we met members of an art league from Savannah; a teacher from Ohio who came with a friend who took cooking classes while she took drawing classes - they were both going to take tango lessons; and an artist from Texas who was staying for a month-long workshop. A young woman who grew up in Virginia Beach and now lives in San Miguel runs a summer art camp for teenagers. A photographer who had studied with the Santa Fe Workshop, now in its sixth year offering classes in San Miguel, had returned on his own to photograph wrought iron and hacienda chapels, where the ranches' extended families and ranch hands worshiped. And the ex-husband of a friend has spent three years building a luxurious "ruin" with a studio where he lives and paints and entertains. He invited all eight of us for dinner. The male-female ratio in San Miguel is about 20 women to every man.

Communing With Painters

Our accommodations certainly didn't fit the image of the struggling artist's garret. We lived like Spanish royalty in our lavish rented casa , which was on the market for $1.2 million. In colonial fashion, all rooms faced a garden patio. There were five bedrooms with baths on three levels and a large rooftop terrace, with space for wet canvases to dry undisturbed.

We had ample room to set up our easels on the roof and paint the steeple-studded skyline, or we could sketch the fountain in the courtyard.

Elizabeth, the villa's cook, took our shopping list to the market; Lupita, the laundress, washed every sock that hit the floor and changed the linens daily until we told her that wasn't necessary. The tariff for such luxury: $2,000 a week, or less than $300 per person.

We went to art openings, house tours, a hot spring, a ghost town and the nearby towns of Guanajuato - a pastel-hued architectural gem and the birthplace of the painter Diego Rivera - and Delores Hildago, devoid of physical charm but well endowed with pottery factories and the best tiles in all of Mexico.

We went club dancing and horseback riding on a sprawling hacienda. We got manicures, pedicures and massages. We enjoyed street performances of mariachi bands and traditional folk dancing.

Come nightfall, we stampeded to our bright, Talavera-tiled kitchen and the Rite of Eventide: pitchers of margaritas and deep bowls of guacamole, made from avocados and limes and served with homemade chips purchased just hours before in the market. Now came the time for art talk: Who painted where, did you like so-and-so, did you see such-and-such exhibit, who wants to go back to the springs. Someone would compliment another's work, another would offer to share a certain shade of paint.

It was a pause in the day when we got to know each other. There was talk of family, tales of the road and a second round of margaritas.

It had been a risky venture. No one on the trip knew everyone, but everyone knew someone. It could have been disastrous, but we clicked - our glasses and as a group.

"Painting is a solitary pursuit," observed Dodson. "Balancing social activity with art is not always easy. You should choose who you travel with carefully. I am here to paint, but the camaraderie is nice."

"I am inspired by how and what other painters see," added Betsy Dalgliesh, 54, a member of our group from Earlysville, Va. "I love the challenge of going to a new place and discovering its own particular charm and then discussing that with others who have a common focus - art - and sharing viewpoints."

Inspirational Sights

Chartreuse. Kiwi. Salsa verde. Lightning bug. Grasshopper. Lime rickey.

We were sharing viewpoints on the color of a shawl someone had bought in the market and was wearing to dinner - the major event of every day, second only to painting. This night the menu included chiles en nogada , a regional favorite representing the colors of the Mexican flag and a work of culinary art. Poblano chilies are stuffed with ground beef or pork, walnuts, fruit and spices and often topped with white sour cream, red pomegranate seeds and green parsley. They earned my salute.

There are more restaurants in San Miguel than galleries and churches combined, and many cater to international tastes. Dinner another night was Asian fusion, fresh salmon in a honey, ginger and smoked chili sauce with an eggplant, mushroom and bell pepper terrine, and lemon curd charlotte for dessert. Bagels were an alternative to huevos con frijoles at breakfast.

Our painting options were also plentiful.

We went twice to the Charco del Ingenio Botanical Garden on the outskirts of town, which includes a canyon, small lake, ancient dam and miles of hiking trails. "It was a religious experience," said Priscilla Whitlock, 56, of Charlottesville. "That's the only way I can describe it."

"It was so gentle and quiet, wonderful birds . . . and after the rains, the cacti burst into bloom. It was my favorite place," said Dalgliesh.

We worked alongside students in the spacious Belles Artes courtyard near the Jardin, enclosed by a two-story stone-and-stucco arcade with tropical vines reaching all the way to the roof. The central fountain was festooned with flowers in an arrangement so fastidious it could have been a cover shot for Architectural Digest. A piano sonata drifted down from a second-floor studio where a music student was practicing, providing a romantic score to silent brush strokes.

Another day, we were mere specks on the vast desolate landscape surrounding an abandoned silver mining company outside of Pozos, a ghost town 45 minutes from San Miguel, where we spent a morning rendering endless shades of white. It was another one of those "pinch me" moments, so spectacular were the ruined building and abandoned mine shafts and barren rocky hills in the background.

Whitlock made a painting, rubbed it out and then began collecting stones to take home. "For the color," she said. "I want to get the color right."

At the Instituto Allende, we shared shaded walkways and an unpretentious, comfortable garden with language students, all old enough to have AARP memberships, who huddled at tucked-away tables working one-on-one with their Spanish-speaking tutors.

It was impossible to resist the churches, beckoning with graceful age and elegance. From the Cinderella Castle-like Parroquia de San Miguel Arcangel to the small mission-style Capilla de San Miguel Viejo, they called to us.

"I felt prayerful," said Holland, describing her emotions as she painted La Iglesia de San Francisco across from our villa, its 1799 facade adorned with saints, cherubs, virgins and vines. I felt a tinge of loss for manners of days gone by when I watched old men remove their hats when passing by the open church doors.

Our blessings in San Miguel were many, but clear morning skies was not one. Most days began in a filmy haze, failing to produce the sharp shadows and contrasts that provide so much of the definition and dimension in art.

But we were given a departing gift. On the last two days, the morning dawned radiantly clear. We went to work like contestants on "Beat the Clock," in a race against the sun to capture that moment of brilliance.

Colors intensified. And so did ours. It was time to pack up and head home.

I guess you could say we were blue. A deep navy blue. And for once, everyone agreed on the color. |