|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | February 2006 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | February 2006

Exploring the Art of Mexico's 'Third Root'

Kevin Nance - The Sun-Times Kevin Nance - The Sun-Times

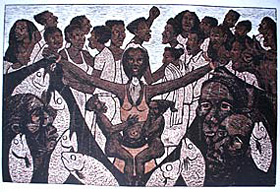

| | "Encuentro de Pueblos Negros" ("The Meeting of Black People") by Mario Guzman Oliveres is part of "The African Presence in Mexico" at the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. |

When Mexican President Vicente Fox made his famously boneheaded remark last year that Mexican immigrants in the United States take jobs "that not even blacks want to do," he unwittingly revealed far more than an insensitivity to African Americans. The remark suggested that Fox was ignorant about the 500-year history of people of African descent in his own country.

But Fox was hardly alone. Many Mexicans, and certainly most Americans, have virtually no inkling about the role of Africans in Mexico: as slaves brought over by the Spanish in the 16th century, as components of the cruel caste system that followed, as heroes in the struggle for independence and as crucial contributors to Mexican culture along with its European and indigenous populations. The existence of Afro-Mexicans, as they've only recently begun to be called, was officially affirmed only in the 1990s, when the Mexican government acknowledged Africa as Mexico's "Third Root."

This epic and largely overlooked history is the grand subject of "The African Presence in Mexico," the sweeping new collection of three exhibits that opened simultaneously last weekend and continue through Sept. 3 at Chicago's Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. It's a landmark undertaking for this Pilsen institution, dwarfing the ambition of its previously best-known project - a handsome retrospective of Frida Kahlo - by at least a factor of 10.

'THE AFRICAN PRESENCE IN MEXICO'

"It's the most important thing we've ever done," museum president Carlos Tortolero told me last week, and I agree. Unlike most major exhibitions of, say, Impressionist painters, which mostly tell us things we already know, "The African Presence in Mexico" tells a virtually unknown and still-unfolding story.

And it tells it well, in what you might call three chapters. The first and largest, "From Yanga to the Present," traces Afro-Mexicans from the founding of the town of Yanga in 1519 as the first free African settlement in the Americas, to their suffering and integration during colonial Mexico in the 18th century and, finally, to their participation in the Mexican Revolution.

The second chapter, "Who Are We Now? Roots, Resistance, and Recognition," charts historic and political collaborations between Mexicans and African Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries. Here we learn about the Underground Railroad to Mexico, which delivered about 100,000 American slaves into freedom between 1829 and 1865, and about the solidarity between a range of Mexican politicians and artists and their African-American counterparts, including Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, whose 1983 campaign was successful in part because of his ability to forge alliances with Mexican Americans.

The final chapter, "Common Goals, Common Struggles, Common Ground," uses video interviews to kick off a dialogue between Chicago's Mexican-American and black communities, which historically have had little direct communication about emerging issues of concern to both, such as gentrification in Pilsen as well as the Bronzeville and Maxwell Street neighborhoods.

"We're not friends, we're not enemies, although there could be problems on the way," Tortolero says. "There's a sense that African Americans today are getting the message that 'Your time is over, it's all about the Mexicans now' - you know, a divide-and-conquer stragegy from the mainstream. The problem is that we just don't talk to each other much, and that's a large part of what this project is meant to address."

Rediscovering history

If all this sounds didactic, perhaps a bit too directly "educational" for an art exhibit, let me assure art lovers that there's plenty of aesthetic value to go along with the history lessons. If you choose to - though I don't recommend it - you can simply wander the galleries in search of beauty.

You'll find plenty. In "From Yanga to the Present," curators Sagrario Cruz-Carretero and Cesareo Moreno have assembled a stunning group of paintings, photographs and sculpture, from anonymous 18th century colonial paintings that show the complexities of the caste system - with its calibration of personal worth in relation to skin color and its tensions between the various societal strata - to the often moving portraits of the Afro-American heroes of the revolution, some by contemporary Afro-Mexican artists belatedly discovering their heritage.

There is, for example, Rufino Tamayo's heroic 1984 oil portrait of Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon, a great military general of African descent who was a major figure in the struggle against Spain (he was captured and executed by the Spaniards in 1815); Morelos is as powerful and dignified as any image of George Washington.

Even more affecting is Agustin Casasola's "Portrait of a Woman Soldier of Michoacan" (1910), a startling sepia-toned photograph of a delicately boned but rough-and-ready revolutionary soldier, her pistol tucked neatly in her waistband, her African face determined and stoic beneath a classic Mexican straw hat.

Ethnic blending in works

Similarly arresting faces - in which African and Spanish qualities mix and meld, reflecting an ethnic integration and intermarriage far more advanced than that of the United States - abound in the exhibit, as in Romualdo Garcia's suite of photographic portraits (circa 1910) and in Mario Guzman Oliveres' "The Meeting of Black People" (2004), a magnificent woodcut print that captures some of the majesty of the best Mexican historical murals.

Also well-represented in the exhibit are works by Elizabeth Catlett, the African-American sculptor and printmaker who spent portions of her career in Mexico, absorbing and expanding on its woodcut and linocut traditions. Among the best of these is "I Have Given the World My Songs" (1948), in which an ageless black woman calmly strums a guitar against a background of violence.

Examining all these images, it's easy to imagine how hurtful Fox's ill-considered comment must have been to many, and how welcome it was when he publicly regretted it. Perhaps he should come to Chicago and see for himself. Beat him to it.

A full range of lectures, guided tours, performances and other educational events accompanies "The African Presence in Mexico" at the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. For more information, call (312) 738-1503 or visit www.mfacmchicago.org. |

| |

|