|

|

|

Entertainment | Restaurants & Dining | February 2006 Entertainment | Restaurants & Dining | February 2006

Some See a Wine Loved Not Wisely, but Too Well

Eric Asimov - NYTimes Eric Asimov - NYTimes

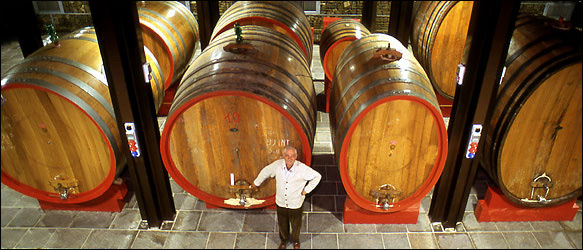

| | Gianfranco Soldera barrel-ages wine in a cellar made with crushed rock, not concrete, which he says destroys wine. (Chester Higgins Jr./NYTimes) |

Montalcino, Italy - You need to have your museum legs for a visit to Il Greppo, the historic estate just south of this hillside town, where the Biondi Santi family virtually invented the wine now prized around the world as brunello di Montalcino. Within minutes of my arrival, Franco Biondi Santi, the family's 84-year-old patriarch, was opening a glass display case and showing me a rifle carried by his grandfather, Ferruccio, when fighting under Garibaldi against Austria in 1866.

It was Ferruccio who, at a time in the 1880's when his fellow Tuscans preferred light, fizzy, semisweet wines, experimented with different strains of the sangiovese grape, locally called the brunello, and created a dry, forceful red wine with the intensity to age and improve for decades. As he has with many visitors before, Franco Biondi Santi took me into his cellar to show me his three remaining bottles of the 1888 Biondi Santi, the first great vintage of brunello. He pointed out the huge fermentation and aging barrels, or botti, made of Slavonian oak, some of which have been in continuous use since the late 19th century. After a lunch that included three vintages of Biondi Santi brunello, he poured out glasses of 1969 moscatello di Montalcino, a delicate, gloriously fragrant and fresh sweet wine that was among the last produced by his father, Tancredi, himself a celebrated viticulturist, before he died in 1970.

"This is the original wine of Montalcino," he said, citing references that go back to the 1500's.

With such a family legacy, it is no wonder that Mr. Biondi Santi is troubled with the state of brunello di Montalcino. Though the 2001 vintage of brunello, which has just been released, may be one of the best ever, questions abound in Montalcino over what kind of wine brunello ought to be, how the wine should be made and where the grapes should be planted.

Since the first half of the 20th century, when Il Greppo's hillside vineyard, 1,600 feet above sea level, was the sole source of brunello di Montalcino, the appellation has grown explosively. Nowadays, vineyards cover hillsides and flatlands all over the Montalcino zone, in all sorts of soils and at many different altitudes, and producers employ almost as many different techniques for making the wine as there are sausages in a salumeria.

Strict traditionalists like Mr. Biondi Santi and his ally, Gianfranco Soldera, whose Case Basse di Soldera wines may be the greatest brunellos of all, scorn much of what passes for brunello di Montalcino today. They say the wine too often is fruity, round and rich, without any semblance of the classic angular, austere sangiovese character of old. Brunellos aged in barriques, or small barrels of new French oak, rather than in botti, they say, might as well be coming from California or Australia for all the distinctiveness they possess.

"If a producer puts wines in barriques, it's because he has bad wine, without tannins," Mr. Soldera said. "He must replace the tannins and aromas with what is gained from the barriques."

Others, however, assert that brunello di Montalcino has never been better, and point to the high demand around the world as evidence of brunello's success. They applauded the relaxing of rules that used to require that wines be aged in barrels for four years before being released. Now, although Montalcino still has the longest aging requirement in Italy, only two of those four years must be in wood, unless it is a riserva, which must be aged for five years, half the time in wood.

"As new producers came on the scene, I would say the average quality has stayed pretty high, and the changes they have made to the laws have been quite beneficial," said Leonardo Lo Cascio, president of Winebow, an Italian wine importer for more than 25 years.

Many traditionally minded producers accuse others of wanting an even more drastic change: eliminating the rule requiring that brunello be made only from the sangiovese grape. Indeed, they insist that some producers are already adding wine made from grapes other than sangiovese to darken the color and to make the wine easier to drink at an early age. They point to recent allegations of fraud in the neighboring Chianti Classico region and say it is only a matter of time before such cases surface in Montalcino.

"I think what has happened in the last few months in Chianti is only the tip of the iceberg," said Francesco Cinzano, chairman of Col d'Orcia, which makes Poggio al Vento, a fine, traditional style riserva brunello.

Filippo Fanti, a brunello producer and head of the Consorzio del Vino Brunello di Montalcino, the local trade association, said most producers supported the sangiovese rule and that any discussion of changing it was "theoretical."

Stylistic conflict, of course, is as much a part of winemaking as corks and barrels. Whether in California, Bordeaux, Burgundy or Barolo, those who adhere to winemaking tradition are always scandalized by those who do not feel bound by it. But the conflict has special resonance in Montalcino, a rare wine region where the origin of the style is still fresh in memory and where the inventor has a direct line to the present in the Biondi Santis. Indeed, the Biondi Santi family might have been quite content back in the 1960's if nobody but themselves had been permitted to call their wine brunello di Montalcino, and they continue to feel a special sense of guardianship for the wine.

Contrary to the popular perception that European winemaking traditions have been honed over centuries of trial and error, brunello di Montalcino is a relatively recent phenomenon. Through the first half of the 20th century, only the Biondi Santis made brunello di Montalcino, and in 1960, only 11 producers were bottling their wine, with about 157 acres planted with sangiovese grosso, the brunello grape.

But by 1990, more than 3,000 acres were planted, with 87 producers making brunello, and today, according to the Consorzio del Vino Brunello di Montalcino, the trade association, nearly 4,700 acres are planted, with 183 producers.

With such growth, the brunello style evolved in different directions. While it is hazardous to speak too generally about styles, wines in the more traditional mode are usually characterized by a ruby color and a lean, spare texture, with good acidity, structure that comes from tannins in the grapes rather than from tannins imparted by oak barrels, and flavors of bitter cherry and smoke. Producers include Il Poggione, Cerbaiona, Poggio di Sotto, Il Palazzone, Col d'Orcia and Lisini.

Wines in the more modern mode tend to be darker, plusher and less acidic, with tannins derived from oak barrels and opulent flavors of fruit and chocolate. Producers in this style include Uccelliera, Camigliano, Fanti, Casanova di Neri and La Poderina. And many producers, like Caparzo, Castelgiocondo, Mastrojanni and Ciacci Piccolomini d'Aragona toe a middle line.

To taste a traditionally made brunello like Biondi Santi or Soldera is to wonder why anybody would ever want to make a different sort of wine. The Biondi Santis today are often criticized as too lean and austere and are said to require too much aging, but to my taste they are like precisely cut gems, offering clearly delineated flavors that, even in a relatively young 1999, are simultaneously graceful and intense rather than lush and rich.

Mr. Soldera takes just as extreme an approach to winemaking as the Biondi Santis, perhaps even more so. He keeps his wine in large botti well beyond the required two years. While most producers are releasing their 2001 brunellos, his 2000 is still in wood "whatever the wine needs," he said. He is a decidedly opinionated man who recently constructed a new cellar with walls of crushed rock rather than cement, which he says destroys wine. On a visit to his cellar he laid down the ground rules: "I don't allow spitting."

Not that I would want to spit this wine. Even in barrels, it has an unusual purity and grace, tannic perhaps, but with a lacy delicacy as well. Though you may drain a glass, you can't say the glass is empty. The aroma lingers.

Mr. Soldera points to the wine, the color of polished rubies, and assails those who assess a wine by the depth of color. "Judging wine by a dark color is for stupid people," he said. "This is the color of sangiovese. You should be able to look through the wine and see your fingernail on the other side."

Unlike Biondi Santi, Soldera wines have maintained their critical reputation and can command up to $200 or $300 a bottle. But traditional brunellos are still available at more modest prices, though they are hardly inexpensive. A subtle, stylish brunello from a producer like Il Poggione can run $50, while a more intense, though equally elegant, riserva might be $75.

Fabrizio Bindocci, the director of Il Poggione, is suspicious of those who stray from traditional methods. He believes that brunello ought to be a long-aged wine and says that proposals to relax the aging requirements even further come from producers with deficient wine.

"Some brunellos on the market should age only two years because they're so thin," he said. "But ours have such structure they need the time."

Iano de Grazia, a partner with his brother in Marc de Grazia Selections, a wine brokerage in Florence, counts himself as favoring traditional brunello, but says the aging rules are too restrictive, and are especially harmful in weak vintages.

"Maybe there should be some limit, but each vintage will tell you," he said. "It shouldn't be a stone recipe. That's crazy."

Not all changes have been so controversial. Few would dispute that viticulture has improved dramatically in the last 35 years, or that replacing rustic chestnut barrels with oak has been a good thing.

For his part, Mr. Biondi Santi has a proposal of his own. He would like to see the Montalcino zone divided into a series of subzones, each with its own character, rather than having so many contrasting styles lumped together as Montalcino. He points to the communes that make up the Cτte d'Or in Burgundy as the perfect example, but acknowledges that this is unlikely to happen as it would not be in most producers' interests.

What else would he like to see happen? He answers quickly.

"No more vineyards in clay soil, or below 1,000 feet. Return to Slavonian oak. Return to three years in wood. Abolish barriques."

"That would be sufficient." |

| |

|