|

|

|

Entertainment | April 2006 Entertainment | April 2006

With Movie Due, 'Da Vinci' Debate Persists

Richard N. Ostling - Associated Press Richard N. Ostling - Associated Press

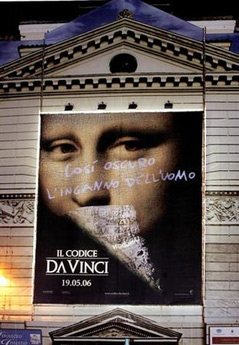

| | Advertising for the upcoming film 'The Da Vinci Code' appears on the scaffolding of St. Pantaleo church in Rome, April 25, 2006. The Italian government said on Tuesday it would remove the massive advertisement after complaints from clergy. (Franceschi-Gisone/Reuters) |

A line from Dan Brown's "The Da Vinci Code" tells you why it's easily the most disputed religious novel of all time: "Almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false."

With 46 million copies in print, "Da Vinci" has long been a headache for Christian scholars and historians, who are worried about the influence on the faith from a single source they regard as wrong-headed.

Now the controversy seems headed for a crescendo with the release of the movie version of "Da Vinci" May 17-19 around the world. Believers have released an extraordinary flood of material criticizing the story books, tracts, lectures and Internet sites among them. The conservative Roman Catholic group Opus Dei, portrayed as villainous in the story, is among those asking Sony Corp. to issue a disclaimer with the film.

Bart Ehrman, religion chair at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, likens the phenomenon to the excitement in the 19th century when deluded masses thought Jesus would return in 1844.

The novel's impact on religious ideas in popular culture, he says, is "quite unlike anything we've experienced in our lifetimes."

To give just one example, Ben Witherington III of Asbury Theological Seminary is following up the criticisms of the novel in "The Gospel Code" with lectures in Singapore, Turkey and 30 U.S. cities. He's given 55 broadcast interviews.

Assaults on "Da Vinci" don't just come from evangelicals like Witherington, or from Roman Catholic leaders such as Chicago's Cardinal Francis George, who says Brown is waging "an attack on the Catholic Church" through preposterous historical claims.

Among more liberal thinkers, Harold Attridge, dean of Yale's Divinity School, says Brown has "wildly misinterpreted" early Christianity. Ehrman details Brown's "numerous mistakes" in "Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code" and asks: "Why didn't he simply get his facts straight?"

The problem is that "Da Vinci" is billed as more than mere fiction.

Brown's opening page begins with the word "FACT" and asserts that all descriptions of documents "are accurate."

"It's a book about big ideas, you can love them or you can hate them," Brown said in a speech last week. "But we're all talking about them, and that's really the point."

Brown told National Public Radio's "Weekend Edition" during a 2003 publicity tour he declines interviews now that his characters and action are fictional but "the ancient history, the secret documents, the rituals, all of this is factual." Around the same time, on CNN he said that "the background is all true."

Christian scholars beg to differ. Among the key issues:

Jesus' divinity.

Brown's version in "Da Vinci": Christians viewed Jesus as a mere mortal until A.D. 325 when the Emperor Constantine "turned Jesus into a deity" by getting the Council of Nicaea to endorse divine status by "a relatively close vote."

His critics' version: Larry Hurtado of Scotland's University of Edinburgh, whose "Lord Jesus Christ" examines first century belief in Jesus' divinity, says that "on chronology, issues, developments, and all the matters asserted, Brown strikes out; he doesn't even get on base."

He and others cite the worship of Jesus in epistles that Paul wrote in the 50s A.D. One passage teaches that Jesus, "though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped" and became a man (Philippians 2:6).

Historians also say the bishops summoned to Nicaea by Constantine never questioned the long-held belief in Jesus' divinity. Rather, they debated technicalities of how he could be both divine and human and approved a new formulation by a lopsided vote, not a close one.

The New Testament.

Brown's version: "More than 80 gospels were considered for the New Testament" but Constantine chose only four. His new Bible "omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ's human traits and embellished those gospels that made him godlike. The earlier gospels were outlawed, gathered up and burned." The Dead Sea Scrolls and manuscripts from Nag Hammadi, Egypt, were "the earliest Christian records," not the four Gospels.

Critics: Historians say Christians reached consensus on the authority of the first century's four Gospels and letters of Paul during the second century. But some of the 27 New Testament books weren't universally accepted until after Constantine's day. Constantine himself had nothing to do with these decisions.

Some rejected writings are called gospels, though they lack the narrative histories that characterize the New Testament's four. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were earlier and won wide consensus as memories and beliefs from Jesus' apostles and their successors.

The rejected books often portrayed an ethereal Jesus lacking the human qualities depicted in the New Testament Gospels the exact opposite of Brown's scenario. Gnostic gospels purported to contain secret spiritual knowledge from Jesus as the means by which an elite could escape the material world, which they saw as corrupt. They often spurned Judaism's creator God and the Old Testament.

On the question of mass burning of texts deemed heretical, Ehrman of North Carolina says there's little evidence to support that claim. Rejected books simply disappeared because people stopped using them, and nobody bothered to make new copies in an age long before the printing press.

The Dead Sea Scrolls? These were Jewish documents, not Christian ones. The Nag Hammadi manuscripts? With one possible exception, these came considerably later than the New Testament Gospels.

Jesus as married.

Brown's version: Jesus must have wed because Jewish decorum would "virtually forbid" an unmarried man. His spouse was Mary Magdalene and their daughter inaugurated a royal bloodline in France.

Critics: First century Jewish historian Josephus said most Jews married but Essene holy men did not. The Magdalene myth only emerged in medieval times.

Brown cites the Nag Hammadi "Gospel of Philip" as evidence of a marriage, but words are missing from a critical passage in the tattered manuscript: "Mary Magdalene (missing) her more than (missing) the disciples (missing) kiss her (missing) on her (missing)."

Did Jesus kiss Mary on the lips, or cheek or forehead? Whatever, Gnostics would have seen the relationship as platonic and spiritual, scholars say.

James M. Robinson of Claremont (Calif.) Graduate School, a leading specialist, thinks the current popularity of Mary Magdalene "says more about the sex life (or lack of same) of those who participate in this fantasy than it does about Mary Magdalene or Jesus."

The whole "Da Vinci" hubbub, Witherington says, shows "we are a Jesus-haunted culture that's biblically illiterate" and harbors general "disaffection from traditional answers."

But he and others also see a chance to inform people about the beliefs of Christianity through the "Da Vinci" controversy.

"If people are intrigued by the historical questions, there are plenty of materials out there," Yale's Attridge says.

British Justice Peter Smith, who recently backed Brown against plagiarism charges, perhaps best summed up the situation in his decision:

"Merely because an author describes matters as being factually correct does not mean that they are factually correct. It is a way of blending fact and fiction together to create that well known model 'faction.' The lure of apparent genuineness makes the books and the films more receptive to the readers/audiences. The danger of course is that the faction is all that large parts of the audience read, and they accept it as truth."

"Da Vinci" publicity: http://www.davincicode.com

Catholic site: http://www.jesusdecoded.com

Evangelical site: http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/special/davincicode.html |

| |

|