|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | April 2006 Travel & Outdoors | April 2006

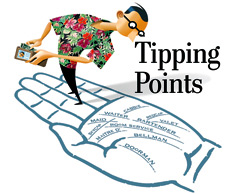

Tipping and Travel: It's No Easy Equation

Cindy Loose - Washington Post Cindy Loose - Washington Post

| | Knowing when to tip and how much to give can confuse any traveler, regardless of the destination. We help you do the math. (Steve McCracken/Washington Post) |

If ever there was a good time to show off, it was then.

Joe Feldman of the District had just walked into a South Beach restaurant to celebrate a friend's 40th birthday, and in the height of coincidence, who should be at a nearby table but his soon-to-be-ex-wife and her soon-to-be-next husband. Feldman made what he thought was an important point by buying his party a magnum of Dom Perignon.

"I was still okay with it until the check came, and then I suddenly felt horrified by the thought of a $75 or $100 tip merely to open a bottle and pour. What is an appropriate tip at that point?"

Ah, the angst of tipping. When we invited readers to tell us their tipping dilemmas and stories, in they poured.

Okay, so most people know that 15 to 20 percent of the bill before tax is the accepted standard in the United States for tipping a waiter. But what about a sommelier who only uncorks and pours your wine? The question takes on more urgency the more expensive the beverage.

And what about the free breakfast buffet included in a hotel charge? Or the free shuttle service? Or the guy who delivers a free toothbrush to your room? And what if both food and service are awful but it's clearly the kitchen's fault, not the waiter's?

Complications and ethical concerns simply multiply overseas. Customs vary not only by country, but more recently, by city. Even if you know the customary percentage, figuring out a foreign currency on the fly can be maddening.

Take Romania, for example, which is in the process of converting to a new currency but still has the old one floating around. One new leu (it's also called lei) equals about 34 cents in U.S. currency, and equals 10,000 old leu. So quickly: your cab fare is 16 new leu. You're tipping in old leu. How much do you give?

For Dragos Mandruleanu of Reston, a miscalculation resulted, he later realized, in his giving a $55 tip for a $5.50 cab ride.

We also heard from people who had been chased down the street because they'd tipped too little -- or even across the desert, in the case of a woman who apparently gave too little to an Egyptian boy on a donkey who'd posed for a picture.

Travelers who have forgotten much of an overseas trip still remember their tipping debacles. Lee Austin of Chapel Hill, N.C., recalls guessing at the appropriate tip in a Paris cafe shortly after arriving in France as a foreign student in 1947. She can still visualize the haughty look on the face of the waiter who returned her tip, saying, "You must need this, Mademoiselle, more than I do."

How much to tip is just the start -- what about the "who?"

"How safety-conscious he is," Kevin Wolf of Arlington thought to himself when an Italian boatsman repeatedly told him to be careful as he transferred from the man's tiny boat to an oceangoing vessel on open water. The man kept warning, "tip," "tip."

"I used my only two words of Italian -- grazie and prego -- many times and got out safely, gesturing the whole time that I was being careful," Wolf says. "Once on the larger boat, I looked back and noticed that all the other tourists in the other little boats were giving their drivers a tip. Oops."

Everyone wants to avoid the "oops" factor. Our clip-and-save cheat sheet (on Page 6) will help in many cases. But given the lack of worldwide standardization, first consider some global tipping tips and philosophies:

· Check the bill. In much of Europe and South America, it's common for a restaurant to put a service charge on the bill, and in fact the obligatory tip can show up anywhere. Unless you like double tipping, it's always wise to see whether you've already been assessed. Then again, the presence of a service charge on a bill isn't a guarantee that the staff's expectations have been met. In Brazil, for example, restaurants typically add a 10 percent service charge, but it's customary to add an extra 5 percent. In France, a service charge is usually included, but if you want to make it clear you're saying thank you, spare change means "merci."

· Do some prep before traveling abroad. Customs change at nearly every national border, and there are even variations within countries. In China, for example, you'll find workers who have never heard of tips, but service workers in larger cities have discovered the joys of tipping, and a gratuity can now be expected. In fact, some restaurants in much-visited places such as Shanghai even add a gratuity to the bill.

In Egypt, it sometimes seems that everyone wants a tip. Then again, a tip could be considered an insult in Japan, Nepal and Taiwan, to name a few countries. In Cuba, it's considered polite to hand the server the tip.

No way around it: You need to investigate tipping customs before you go. Most guidebooks offer a rundown, and a handful of countries are covered at the Original Tipping Page Web site, http://www.tipping.org/ (you'll also find links there that lead to, among other things, a Cornell University study of dozens of other countries). The book "The Itty Bitty Guide to Tipping" by Stacie Krajchir and Carrie Rosten (Chronicle Books, $6.95) gives a detailed report on the United States and a rough rundown of a few dozen countries.

· Learn the currency, or take a crib sheet. Most mistakes, judging from reader reports, aren't because a traveler didn't know the customs. They happened because the traveler didn't know the currency or couldn't do the math quickly enough.

There are bellmen in Zimbabwe who no doubt are still talking about the outrageously generous tips handed out when Thomas Worthington of Cascade, Md., first arrived and hastily converted way in their favor.

On the other hand, Howard Smith of Westminster, Md., meant to tip a Beijing pedicab driver $3 for a long ride and is still feeling bad about realizing too late that he "gave the poor, hardworking man 35 cents."

Memorizing the value of a dollar, a five and a ten in yuan or shekels before you hit a new border could save you either embarrassment, or lots of yuan and shekels. If the translation isn't sticking in your head, don't be too proud to make a cheat sheet ( http://www.oanda.com/ has a good one you can print out; under Currency Tools, click FXCheatSheet). Changing some dollars before leaving home guarantees you'll be ready for the first tip-deserving worker you meet.

· Don't unload U.S. coins. Sam Peach of Ijamsville, Md., woke up in a Mexican hotel and discovered a couple of dollars in U.S. change in the planter outside his door. It was the same change he'd given the bellman the night before, when he'd arrived without pesos or small U.S. bills.

Peach is just one of several readers who wrote to tell us how under-appreciated quarters are abroad: U.S. coins are worthless, since currency exchange agencies won't turn them into local money.

Dollar bills, on the other hand, will do the trick in developing countries. They do mean that the receiver has to convert them at a bank or currency exchange company. On the other hand, in places where the black market is paying more than the official exchange rate, dollars might be appreciated. In such cases, bring a roll of singles.

· Be kind when service is bad. Tipping nothing to workers whose incomes depend on it is unfair, even if you are dissatisfied with the service, numerous experts agreed.

"You could leave maybe 10 percent, but also complain to the manager on the assumption he cares and will try to improve service for someone else, if not for you," said Tim Zagat, founder and chief executive of Zagat Survey.

Etiquette specialist and author Letitia Baldrige also endorses this approach if service is particularly bad. "You don't know," she said. "Maybe the person who gave you bad service has a wife in the throes of cancer or is losing his house that day."

"Tipping is a morally dubious practice to begin with: People should be paid for what they do and not have to rely on the kindness of strangers," said Arthur Dobrin, a professor of humanities and ethics at Hofstra University. "But leaving no tip is doubly immoral. Where else can you get away with that? If I don't like my doctor, I don't go back. You don't like the service, complain to management."

Besides, he noted, bad service is often not the fault of the server. A hotel worker may respond slowly because there aren't enough employees. The food might be late in arriving because the chef is acting up.

Moreover, the person you deal with directly might be sharing his tips with people behind the scenes who are doing an exemplary job, so why punish everyone?

If someone is rude and obnoxious, that's a different matter, said Dobrin, but he added, "Most complaints I suspect are things like they wanted their steak rare and it came out medium, or they didn't want their potatoes touching their meat."

· Err on the side of generosity. Glen Stassen, an ethics professor at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif., argues that as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, "I feel an ethical obligation to tip more than most people do; I don't go by the rules of what is usual."

Zagat believes that degree of generosity is over the top, but even he agrees that if you feel happy and grateful, no arbitrary tipping rule should stop you from being magnanimous. When traveling in the developing world, even a 20 percent tip on a meal in a little local restaurant might amount to no more than small change. Some readers worried that giving a larger percentage than is customary might seem arrogant or create unfair expectations for the next traveler.

Not to worry, experts agreed.

"On a $3 meal at a local restaurant in a poor country, I'd probably leave a dollar," said ethicist Dobrin. "That's not spoiling anyone. And if that person expects a dollar from the next rich person who comes along, what's the harm?" In such situations, Zagat continues to follow his theory that a tip should be given out of gratitude, not guilt. But that doesn't mean he wouldn't tip generously.

"At Newton Circus in Singapore, where they have about 50 little booths each serving a small dish, I was getting things for $1 and tipping $2. Normally I try to stay within the customs of a country, but I'm not sitting there thinking, 'Oh my God, I'm going to break the rules and look like an ugly American'," Zagat said. "If I'm happy and in wonderment, I may make a big gesture of thanks."

As for Joe Feldman: Experts agreed he didn't need to come up with an extra $100 for the guy who uncorked his Dom Perignon. A sommelier who recommends a great bottle of wine at a good price deserves at least a 10 percent tip, Zagat said. But for simply uncorking an over-the-top expensive bottle you've chosen, 20 bucks or so should do the trick. |

| |

|