|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | May 2006 Entertainment | Books | May 2006

Coming to America

Tamar Jacoby - Newswire Tamar Jacoby - Newswire

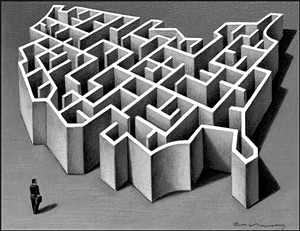

| LOCKOUT - Why America Keeps Getting Immigration Wrong When Our Prosperity Depends On Getting It Right

Michele Wucker

PublicAffairs. 288 pp. $25.95 |

A timely new book argues that barring U.S. doors to immigrants is folly.

About halfway through Michele Wucker's timely book Lockout, she spends a few days with the 40 finalists competing in the 2005 Intel Science Talent Search. These are formidably bright high school seniors already doing scientific research not just a notch or two above their peers' work but well beyond the understanding of most adults. And, as at most science and math competitions in the United States today, the Intel finalists are disproportionately immigrants or the children of immigrants.

As Wucker mingles among these foreign-born best and brightest, exploring their personal stories, it's hard to miss her point: We need this talent. And any policy that helps us take advantage of it will be good not only for the immigrants and the United States but also for the world, which will eventually reap the benefits of what these new Americans produce.

In a season when the country has been caught up in a national conversation about immigration, Wucker, a fellow at the World Policy Institute, has come out with a forcefully argued and informative book. It's far from comprehensive, and some parts of her case are stronger than others. But the overarching argument - that, as her subtitle puts it, "America Keeps Getting Immigration Wrong When Our Prosperity Depends on Getting It Right" - is both correct and important.

The stakes could hardly be higher. Some 1.5 million foreigners enter and settle in the United States each year, the overwhelming majority of them to search for work. This is a historic high point: the largest absolute number of immigrants in our history (though not the largest percentage of the U.S. population). Unlike at the turn of the 20th century, when the majority of the newcomers came from Europe, today more than half come from Latin America and a quarter from Asia. The problem is that U.S. immigration quotas accommodate only about two-thirds of this influx, and the spillover - a half-million illegal immigrants each year - is creating problems from coast to coast, undermining the rule of law, endangering U.S. security and souring native-born Americans' attitudes toward all newcomers. With the White House and Congress deep in debate about the issue, Wucker usefully lays out what's wrong with the current system and summarizes the key arguments for the package of changes being discussed by lawmakers.

The book's most vivid and informative chapters deal with a subject not much highlighted in the media in recent months: the highly educated, highly skilled immigrants who account for, by my calculations, perhaps 10 to 15 percent of the current annual influx. It's not just our top math and science students who are immigrants; it's also a quarter of our PhDs, a quarter of our doctors and nurses, some 40 percent of our science and engineering doctorates and a corresponding four in 10 of our top scientists and engineers. Without them, Silicon Valley would not have happened, America's growing shortage of doctors and nurses would be a national emergency, and the U.S. R&D engine that has been driving globalization around the world would be sputtering ominously, if not petering out. Wucker introduces readers to these newcomers and underscores the importance of the contributions they make, scolding us fervently and urgently for taking them for granted.

Her concern is that our ambivalent attitudes toward foreigners and globalization, combined with our broken immigration bureaucracy, are going to deprive us of this talent. Her case is somewhat exaggerated. In one chapter, for instance, she imagines a day without not just Mexicans but without any immigrants, skilled or unskilled. This is downright silly; no one is thinking of sealing America's borders to top-level scientists. But she's on the money when she argues that we let in too few of these people, that our immigration bureaucracy handles their cases poorly and that, as a result, more and more prospective Americans would now rather immigrate to other countries.

Wucker frames her brief about the importance of welcoming skilled newcomers with a broader case about immigration generally. Americans, she argues, have always been ambivalent about foreigners, and we made a critical wrong turn at the start of the 20th century when the "Americanization" movement, which initially focused on helping immigrants adapt to life in the United States, turned coercive and xenophobic. Our post-Sept. 11 fears of jihadist infiltration have made a bad situation worse. We need to change course now, Wucker writes, and bring our immigration policy more into line with our labor needs, even as we rethink our wider approach to ethnicity and assimilation. She's right on all points, and she argues them passionately.

Things begin to go wrong when she moves beyond broad brush strokes to look more closely at American attitudes and immigration policy. Part of the problem is the fervor of her beliefs, which often seems to get the better of her writing. While she recognizes in her more sober moments that Americans have mixed feelings about immigrants - at once welcoming, fearful and resentful - too frequently she sounds as if the United States were one step away from xenophobic meltdown, or, as she puts it, a "lockout."

Her opening description of American attitudes is "us-versus-them . . . isolationism." Her picture of the 20th-century reaction to immigration is a litany of horrors: persecution, hate crimes, lynchings and internments. All these abuses happened on occasion, to our great shame, and from 1924 to 1965 the United States sharply restricted the number of immigrants we admitted. But Wucker's portrait of a nation violently hostile to all things foreign is misleading, and her unrelentingly alarmist tone works, if anything, to undermine her case.

When she gets to the present, she paints a vivid, damning picture of the excesses that occurred in the wake of 9/11: Middle Eastern men were required to register with the government, several hundred were detained under unusually harsh circumstances, and several thousand were eventually ordered to leave the country, often for technical legal violations. Meanwhile, heightened security checks made for long delays and growing backlogs. But here, too, Wucker seems to miss the forest for the trees. After all, for all the discrimination and inconveniences (and the skilled immigrants who decided to go elsewhere as a result), even in the wake of the attacks, we have not tightened our immigration policy - the criteria for whom and how many immigrants we admit remain unchanged. Indeed, on Thursday, the Senate passed landmark, liberalizing legislation that would bring U.S. immigration quotas more into line with our labor needs and legalize some 12 million illegal immigrants.

Wucker endorses these changes in her last chapter, although, strangely enough, with few hints that anyone else is discussing them. Her recommendations also seem somewhat muddled, if not contradictory. She argues, quite rightly, for "a system that allows the people our economy needs to come here legally." But in the very same chapter, she proposes that we reduce the number we admit - a change that would have the effect of strangling large parts of the economy. What Wucker seems to be saying is that we need more skilled workers and fewer unskilled. But this is far from true: We also need a great many more unskilled laborers than we now admit legally - something she does not seem to recognize.

When it comes to assimilation - that mysterious alchemy by which immigrants become Americans - Wucker would like to strike a middle course between those who feel that the process must mean a renunciation of ethnicity and those who glorify difference at any cost, including the cost of a common mainstream culture. Once again, she makes an appealing, broad-brush case but never goes deeper - never tells us how Americans might balance what she calls "symbolic" ethnicity with shared civic values and patriotism. Not only is it unclear what she means by "symbolic," but when she writes about immigrants' attachments to their home countries - arguing, for example, that people should be able to vote in two nations - she seems to endorse something far more than symbolism.

Are today's immigrants - and their American-born children - likely to get the immigrant bargain right? Can we find a way to admit the robust influx that's in our interest and all but inevitable in a globalizing world while maintaining our civic values and sense of ourselves as a nation? At the end of Lockout (somewhat surprisingly, given her emphasis on American xenophobia), Wucker predicts hopefully that we are just a step or two from striking that balance. She's plainly right that we need to do so - and, indeed, in urging that we forge a more realistic policy, she helps sketch the road map. If only the dire rest of her book had not painted the destination as so hopelessly far away.

Tamar Jacoby, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, is the editor of "Reinventing the Melting Pot: The New Immigrants and What It Means To Be American." |

| |

|