|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | September 2006 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | September 2006

Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere

John Noble Wilford - NYTimes John Noble Wilford - NYTimes

|

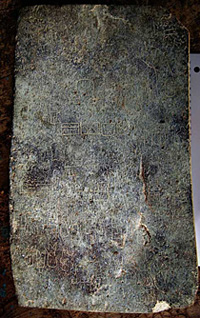

Click image to enlarge. | | Sixty-two distinct signs are inscribed on the stone slab, which was discovered in the state of Veracruz in Mexico. (Stephen Houston) |

A stone slab bearing 3,000-year-old writing previously unknown to scholars has been found in the Mexican state of Veracruz, and archaeologists say it is an example of the oldest script ever discovered in the Western Hemisphere.

The Mexican discoverers and their colleagues from the United States reported yesterday that the order and pattern of carved symbols appeared to be that of a true writing system and that it had characteristics strikingly similar to imagery of the Olmec civilization, considered the earliest in the Americas.

Finding a heretofore unknown writing system is rare. One of the last major ones to come to light, scholars say, was the Indus Valley script, recognized from excavations in 1924.

Now, scholars are tantalized by a message in stone in a script unlike any other and a text they cannot read. They are excited by the prospect of finding more of this writing, and eventually deciphering it, to crack open a window on one of the most enigmatic ancient civilizations.

The inscription on the Mexican stone, with 28 distinct signs, some of which are repeated, for a total of 62, has been tentatively dated from at least 900 B.C., possibly earlier. That is 400 or more years before writing was known to have existed in Mesoamerica, the region from central Mexico through much of Central America, and by extension, anywhere in the hemisphere.

Previously, no script had been associated unambiguously with the Olmec culture, which flourished along the Gulf of Mexico in Veracruz and Tabasco well before the Zapotec and Maya people rose to prominence elsewhere in the region. Until now, the Olmec were known mainly for the colossal stone heads they sculptured and displayed at monumental buildings in their ruling cities.

The stone was discovered by María del Carmen Rodríguez of the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico and Ponciano Ortíz of Veracruz University. The archaeologists, a married couple, are the lead authors of the report of the discovery, which is being published today in the journal Science.

The signs incised on the 26-pound stone, the researchers said in the report, “link the Olmec to literacy, document an unsuspected writing system and reveal a new complexity to this civilization.”

Noting that the text “conforms to all expectations of writing,” the researchers wrote that the sequences of signs reflected “patterns of language, with the probable presence of syntax and language-dependent word orders.”

Several paired sequences of signs, scholars said, have even prompted speculation that the text contained poetic couplets.

Experts who have examined the Olmec symbols said they would need many more examples before they could hope to read what is written on the stone. They said it appeared that the symbols in the inscription were unrelated to later Mesoamerican scripts, suggesting that this Olmec writing might have been practiced for only a few generations and never spread to surrounding cultures.

Stephen D. Houston of Brown University, a co-author of the report and an authority on ancient writings, acknowledged that the apparent singularity of the script was a puzzle and would probably be emphasized by some scholars who question the influence of the Olmec on the course of later Mesoamerican cultures.

But Dr. Houston said the discovery “could be the beginning of a new era of focus on the Olmec civilization.”

Other participants in the research include Michael D. Coe of Yale; Richard A. Diehl of the University of Alabama; Karl A. Taube of the University of California, Riverside; and Alfredo Delgado Calderón, also of the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Mesoamerican researchers not involved in the discovery agreed that the signs appeared to represent a true script and that their appearance could be expected to inspire more intensive exploration of the Olmec past. The civilization emerged about 1200 B.C. and virtually disappeared around 400 B.C.

In an accompanying article in Science, Mary Pohl, an anthropologist at Florida State University who has excavated Olmec ruins, was quoted as saying, “This is an exciting discovery of great significance.”

A few other researchers were skeptical of the inscription’s date because the stone was uncovered in a gravel quarry where it and other artifacts were jumbled and possibly out of their original context.

The discovery team said that ceramic shards, clay figurines and other broken artifacts accompanying the stone appeared to be from a phase of Olmec culture ending about 900 B.C. They conceded, though, that the disarray at the site made it impossible to determine if the stone was in a place relating to the governing elite or a religious ceremony.

Dr. Diehl, a specialist in Olmec research, said, “My colleagues and I are absolutely convinced the stone is authentic.”

Road builders digging gravel came across the stone in debris from an ancient mound at Cascajal, a place the discoverers said was in the “Olmec heartland.” The village is on an island in southern Veracruz and about a mile from the ruins of San Lorenzo, the site of the dominant Olmec city from 1200 B.C. to 900 B.C.

That was in 1999, and Dr. Rodríguez and Dr. Ortíz were called in, and they quickly recognized the potential importance of the find.

Only after years of further excavations, in which they hoped to find more writing specimens, and comparative analysis with Olmec iconography did the two invite other Mesoamerican scholars to join the study. After a few reports in recent years of Olmec “writing” that failed to hold up, the team decided earlier this year that the Cascajal stone, as it is being called, was the real thing.

The tiny, delicate signs are incised on a block of soft serpentine stone 14 inches long, 8 inches wide and 5 inches thick. The inscription is on the stone’s concave top surface.

Dr. Houston, who was a leader in the decipherment of Maya writing, examined the stone with an eye to clues that this was true writing and not just iconography unrelated to a language. He said in an interview that he had detected regular patterns and order suggesting “a text segmented into what almost look like sentences, with clear beginnings and clear endings.”

Some pictographic signs were frequently repeated, Dr. Houston said, particularly ones that looked like an insect or a lizard. He suspected that these were signs alerting the reader to the use of words that sound alike but have different meanings — as in the difference in English of “I” and “eye.”

All in all, Dr. Houston concluded, “the linear sequencing, the regularity of signs, the clear patterns of ordering, they tell me this is writing, but we don’t know what it says.” |

| |

|