|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | October 2006 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | October 2006

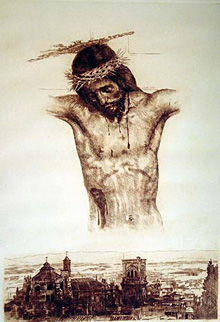

In Mexico, What's Sacred Isn't Safe

Elisabeth Malkin - NYTimes Elisabeth Malkin - NYTimes

| | The Mexican government is now setting in motion a vast project to register sacred art, hoping to enlist parish priests and local congregations to photograph, measure and describe objects. |

San Agustín Zapotlan, Mexico - Only the new iron grille over the entrance of the stone country church here suggests that anything is amiss. One night this summer, thieves forced open a side door, removed an 18th-century painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe from an alcove on the north side of the transept and sliced the painting out of its frame.

They also took 17th-century wooden figures of St. Augustine and St. John the Baptist, leaving the vestments that had adorned them in a heap on the floor.

"We were all trusting," lamented Esteban Cruz, the retired railroad worker who guards the only set of keys to the church, in this village less than two hours northeast of Mexico City. "We knew that they had been robbing the churches. There were rumors that they had stolen in this or that village. But we just trusted that nobody had ever gotten in here."

Thefts from churches have become routine here in the colonial heartland of Mexico, spurred by collectors' demand, a dwindling number of legitimate pieces and what appears to be a remote chance of prosecution.

Looters have picked through Latin America's archaeological sites for centuries. These church robberies are newer, arising as the taste for colonial religious art has grown in the international art market.

Every country in the region has experienced thefts, but the scale is larger in Mexico because of the country's wealth of colonial art.

Since 1999 about 1,000 colonial pieces have been stolen, according to the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico, the government agency that oversees the country's antiquities and colonial heritage. "I think that more than half the pieces end up outside Mexico," said Magdalena Morales, the institute's official in charge of its theft-prevention efforts.

Most of the work is lost forever.

"Cultural patrimony is a nonrenewable resource," warned Clara Bargellini, an art historian at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. "We are suffering losses, partly because we still do not have an accurate count of what exists and where."

The Mexican government is now setting in motion a vast project to register sacred art, hoping to enlist parish priests and local congregations to photograph, measure and describe objects.

Estimated in the millions, they are tucked away in churches, chapels and former monasteries. About 600,000 items have been inventoried so far.

The institute is also preparing its own Web site of stolen art, to counter claims by dealers and collectors that there was no record of a theft. This site will be an improvement, cultural officials suggest, over international databases that are difficult to navigate and incomplete for Mexican pieces.

Sometimes there is a break. In August, the San Diego Museum of Art in California returned an 18th- century painting that had been stolen in 2000 from a church near here. The museum bought the painting, "Expulsion From the Garden of Eden," from a Mexico City dealer.

Because the work was unusual and known to experts, when curators began checking its provenance in 2002, they discovered it had been stolen.

But when there is no record that a piece was ever in a church, there is little hope of recovery. At the church of Santiago Tepeyahualco, also near here, a statue of the infant Jesus was plucked from its glass case in July. The empty case is still there, roped off as a crime scene. But nobody had ever photographed the figure or even jotted down a brief description in a notebook.

"The best news I have heard is that Mexico is embarking on a program of going into the boonies and photographing," said Marion Oettinger, director of the San Antonio Museum of Art in Texas and an expert on Mexican colonial art. "Virtually every village in Mexico has works of art. They are just magnificent."

In theory, the task of registering items in small parish churches should be relatively simple, sped by the Internet and digital photography. In practice, it is more complicated. The separation of church and state has left relationships prickly.

Historical objects in churches, chapels and monasteries belong to the state. So, "the priests ask, 'How can I do an inventory if they are going to take it and send it to a museum?'" said the Reverend José de Jesús Águilar, a director of sacred art for the Mexican Bishops' Conference. Father Águilar estimates that only about 35 percent of parishes have the computers, Internet access and digital cameras needed to download the government's registry sheet, fill it out and send it back.

Even in cases where it was clear that a piece was smuggled out of Mexico, there are no known prosecutions on either side of the border. This was the case with "Expulsion From the Garden of Eden," although the U.S. authorities say they are still investigating. Another such example was the relief of St. Francis stolen from a chapel in the state of Puebla in 2001, which turned up in a gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2002.

Dealers say they are tricked by forged papers. But since 1972 Mexico has forbidden the export of colonial art, even from private collections, with rare exceptions. So, almost by definition, any such work that leaves Mexico has been smuggled.

With virtually no legal exports from Mexico, the supply of legitimate pieces for the international market is shrinking, said Valery Taylor, who runs a New York gallery that used to specialize in this area. "When you see a dealer with a nice big stock of Spanish colonial art," she said, "you'd better be afraid."

SAN AGUSTÍN ZAPOTLAN, Mexico Only the new iron grille over the entrance of the stone country church here suggests that anything is amiss. One night this summer, thieves forced open a side door, removed an 18th-century painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe from an alcove on the north side of the transept and sliced the painting out of its frame.

They also took 17th-century wooden figures of St. Augustine and St. John the Baptist, leaving the vestments that had adorned them in a heap on the floor.

"We were all trusting," lamented Esteban Cruz, the retired railroad worker who guards the only set of keys to the church, in this village less than two hours northeast of Mexico City. "We knew that they had been robbing the churches. There were rumors that they had stolen in this or that village. But we just trusted that nobody had ever gotten in here."

Thefts from churches have become routine here in the colonial heartland of Mexico, spurred by collectors' demand, a dwindling number of legitimate pieces and what appears to be a remote chance of prosecution.

Looters have picked through Latin America's archaeological sites for centuries. These church robberies are newer, arising as the taste for colonial religious art has grown in the international art market.

Every country in the region has experienced thefts, but the scale is larger in Mexico because of the country's wealth of colonial art.

Since 1999 about 1,000 colonial pieces have been stolen, according to the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico, the government agency that oversees the country's antiquities and colonial heritage. "I think that more than half the pieces end up outside Mexico," said Magdalena Morales, the institute's official in charge of its theft-prevention efforts.

Most of the work is lost forever.

"Cultural patrimony is a nonrenewable resource," warned Clara Bargellini, an art historian at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. "We are suffering losses, partly because we still do not have an accurate count of what exists and where."

The Mexican government is now setting in motion a vast project to register sacred art, hoping to enlist parish priests and local congregations to photograph, measure and describe objects.

Estimated in the millions, they are tucked away in churches, chapels and former monasteries. About 600,000 items have been inventoried so far.

The institute is also preparing its own Web site of stolen art, to counter claims by dealers and collectors that there was no record of a theft. This site will be an improvement, cultural officials suggest, over international databases that are difficult to navigate and incomplete for Mexican pieces.

Sometimes there is a break. In August, the San Diego Museum of Art in California returned an 18th- century painting that had been stolen in 2000 from a church near here. The museum bought the painting, "Expulsion From the Garden of Eden," from a Mexico City dealer.

Because the work was unusual and known to experts, when curators began checking its provenance in 2002, they discovered it had been stolen.

But when there is no record that a piece was ever in a church, there is little hope of recovery. At the church of Santiago Tepeyahualco, also near here, a statue of the infant Jesus was plucked from its glass case in July. The empty case is still there, roped off as a crime scene. But nobody had ever photographed the figure or even jotted down a brief description in a notebook.

"The best news I have heard is that Mexico is embarking on a program of going into the boonies and photographing," said Marion Oettinger, director of the San Antonio Museum of Art in Texas and an expert on Mexican colonial art. "Virtually every village in Mexico has works of art. They are just magnificent."

In theory, the task of registering items in small parish churches should be relatively simple, sped by the Internet and digital photography. In practice, it is more complicated. The separation of church and state has left relationships prickly.

Historical objects in churches, chapels and monasteries belong to the state. So, "the priests ask, 'How can I do an inventory if they are going to take it and send it to a museum?'" said the Reverend José de Jesús Águilar, a director of sacred art for the Mexican Bishops' Conference. Father Águilar estimates that only about 35 percent of parishes have the computers, Internet access and digital cameras needed to download the government's registry sheet, fill it out and send it back.

Even in cases where it was clear that a piece was smuggled out of Mexico, there are no known prosecutions on either side of the border. This was the case with "Expulsion From the Garden of Eden," although the U.S. authorities say they are still investigating. Another such example was the relief of St. Francis stolen from a chapel in the state of Puebla in 2001, which turned up in a gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2002.

Dealers say they are tricked by forged papers. But since 1972 Mexico has forbidden the export of colonial art, even from private collections, with rare exceptions. So, almost by definition, any such work that leaves Mexico has been smuggled.

With virtually no legal exports from Mexico, the supply of legitimate pieces for the international market is shrinking, said Valery Taylor, who runs a New York gallery that used to specialize in this area. "When you see a dealer with a nice big stock of Spanish colonial art," she said, "you'd better be afraid." |

| |

|