|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | November 2006 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | November 2006

Border Town Given New Life

Jimmy Patterson - El Universal Jimmy Patterson - El Universal

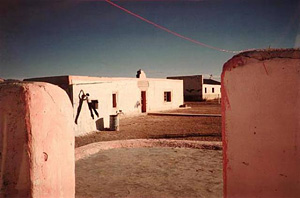

| | Boquillas, Coahuila, a tiny, dusty border town just down the Río Bravo from Big Bend National Park. (Alex Webb) |

Terlingua, Texas - Quilting. Crafting walking sticks. Painting rocks. Scraping together food. Surviving.

There´s not much else to do in Boquillas, Coahuila, a tiny, dusty border town just down the Río Bravo from Big Bend National Park.

Boquillas was once a vibrant village, as tiny, dusty Mexican border villages go.

The people of the town, which topped out at 175 in its heyday in the early part of this decade, welcomed visitors from the park across the river, earning US$2 to boat over travelers eager for a taste of culture, a real Mexican taco and a cold beer.

The people of the town earned their livelihoods by boating and entertaining the park tourists, and by making items and selling them to the Americans.

Some call them tiny works of art. Others trinkets.

But they represented the heart and soul of the humble villagers of this humble place.

And then their world changed.

To protect the United States from terrorists and in an attempt to stem the flow of illegals crossing the border, the U.S. Congress cracked down on U.S.-Mexico border traffic in May 2002.

The people of Boquillas could no longer sell their handcrafts to Americans. No more US$2 boat rides across the Río Bravo. No more donkey rides into town.

The restaurants in town dried up, the people left.

Hope followed close behind. Only the poorest remained.

Now, 4 1/2 years later, thanks to the selfless, almost saint-like sacrifices of a small group of people in this wild, untamed region, the people of Boquillas may yet get back on their feet.

Danielle Gallo was 20 when she first heard of the people of Boquillas.

Living in Marathon, Texas, at the time, Gallo fought wildfires as an employee of the park system. She met men from Boquillas who also were firefighters and would listen to their stories of returning to their abject poverty at the end of work shifts that kept them away from their family for three weeks at a time.

"I could no longer say, ´You go back to your dark holes and I´ll stay here at my home and be comfortable,´ " Gallo said. "It was time to do something."

She began by going to Boquillas and teaching the children.

Her first trip was in November 2003. She stayed eight months, living in an old school house, teaching, surviving, and making friends with the people of Boquillas.

But Gallo said the main point of her stay was to assess the needs of residents.

She returned to the United States and joined up with a former river guide named Cynta de Narváez.

De Narváez was just as aware of the plight of the villagers as Gallo and together they set out to do what they could to make life bearable again for its people.

They started by collecting canned goods from their friends and residents of the Big Bend region of Texas, from Fort Davis and Alpine and Marathon to Terlingua and Marfa.

They opened a small food bank in Terlingua with a 100-pound bag of beans, cans of food and rice.

"I would go around and hit up everyone in the bars for US$20 or US$30 and go buy beans with that," Gallo said. "One lady from Marathon donated a whole trailer load of food."

Because of border restrictions, Boquillans found themselves more than 60 miles from the nearest fuel for purchase.

With no income, they could no longer drive 60 miles to purchase fuel for the water well generator.

Abe and Josie Connally of Terlingua Ranch heard of the people´s plight and donated their time, skills and supplies and built a solar powered generator.

In 2004, the food and generator campaign eventually brought an even larger effort.

"It was that year that I started buying their crafts from them," Gallo said. "Each time I would go to Boquillas, I would pick up their wire scorpions and their bracelets and the things that they had made and go out every night and badger people into buying them and then return the money from sales on the next trip down."

Since their efforts have begun, Gallo and De Narváez have developed relationships with 16 vendors in Fort Davis, Marathon, Alpine, Marfa and Terlingua - people who are themselves eager to help the artisans in the small Mexican village. |

| |

|