Graphic Evidence of Mexico’s Ferment

Grace Glueck - NYTimes Grace Glueck - NYTimes

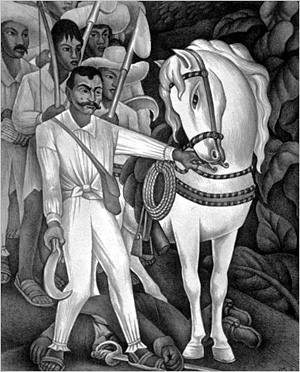

| | “Zapata” (1932), a lithograph by Diego Rivera, is included in “Mexico and Modern Printmaking.” (Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

| | Mexico and Modern Printmaking: A Revolution in the Graphic Arts, 1920-1950 "Untitled (Red Volcano)" by Dr. Atl, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through Jan. 14. (Andrea Simon/Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

Philadelphia — There stands the fierce man, the bridle of his white horse in one hand, a sickle in the other, backed by a ragtag crew carrying spears. This famous lithograph made by Diego Rivera in 1932 depicts Emiliano Zapata, hero of the Mexican Revolution.

Not only is the subject of this vivid print a revolutionary symbol, the print itself belongs to a related revolution, one that took place in Mexican art. It’s a stalwart of the show “Mexico and Modern Printmaking: A Revolution in the Graphic Arts, 1920-1950” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

After the armed conflict that broke out in 1910 and continued for more than a decade, a powerful effort was made by leftist intellectuals, first in murals and then in the graphic arts, to awaken a largely illiterate public to the need for political change, to acquaint it with past and present injustices and to create a national cultural identity linking the Mexican arts-and-crafts tradition with the monuments of the country’s pre-Conquest history.

Rivera (1886-1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) were the Big Three in mural-making, commissioned in the early 1920s to cover walls of important government buildings with rousing propaganda. Spurred by their mural activity, they also took to printmaking, producing posters, portraits, landscapes, vivid depictions of Mexican daily life and other images meant to stir public awareness.

Their achievements and those of many other graphic artists tuned into the crusade are laid out in this exhibition, which displays 125 prints and posters drawn almost entirely from the collections of the Philadelphia museum and the Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. Put together by John Ittmann, curator of prints in Philadelphia, and Lyle Williams, curator of prints and drawings at the McNay, the show could use some trimming, but by and large it’s a stirring account of a movement that brought new energy to Mexican art and life.

An abbreviated history of modern Mexican printmaking might begin with José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), whose widely distributed satirical prints and cartoons made use of folk images like animated skeletons, or calaveras, to parody the doings of the rich and powerful and to denounce injustice. He’s shown here in an admiring 1953 linocut by Leopoldo Méndez (1902-69) that depicts him as an old man, sober and unsmiling, seated at his work table as he draws on a metal block, a pitched battle raging outside his window.

Another giant in the history of the movement, less familiar outside of Mexico, was Gerardo Murillo (1875-1964), a teacher, writer, publisher, artist and admirer of Mexico’s ancient culture. Around 1900 he changed his name to Dr. Atl, the word for water in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs.

Well-versed in European art of his time, and a devotee of early Italian fresco painting, he was a prime mover in the campaign for government sponsorship of murals and a leading exponent of landscape painting, for what he saw as its universal impact. His own work was dominated by his fascination with Mexican volcanoes, and a standout among a group of his vibrant color prints here is “Night” (c. 1911-14), a mysterious rendering of peaks and sprawling shapes in black that glitter with gold against a hazy blue and lavender mound of sky.

The stars of the period — Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros and Rufino Tamayo — are well represented of course. Besides his “Zapata,” Rivera’s many entries include several lithographs of his wife, Frida Kahlo, in the nude (1930) and a fetching full-frontal nude of the beauty Dolores Olmedo (1930), an art collector and entrepreneur who went from making bricks to operating one of Mexico’s biggest construction firms.

The prolific and long-lived Tamayo (1899-1991) is seen, rather disappointingly, in his beginnings as a printmaker, with stark black-and-white woodcuts, wood engravings and linocuts, deliberately crude in execution, that reflect his own Zapotepec heritage. The small “Man and Woman” (1926) shows a barefooted Indian couple against a mountain landscape.

Of the many Orozco prints on view, more than a few depicting social unrest, one of the most powerful is “Negroes” (1934), a wrenching lithograph that portrays several bodies hanging from trees, a relic of his sojourn in the United States from 1927 to 1934. Among outstanding works by Siqueiros are several wonderful portrait heads, including one of his own long, narrow face topped by a mass of tight curls, and a group of 13 small but intense woodcuts made in 1931 from bits of salvaged wood while he was imprisoned for being a member of the Communist Party. Their subject matter is the harsh lot of the poor and oppressed.

One surprise is the extent of American involvement in the Mexican print movement, particularly that of the Weyhe Gallery, a presence in New York City for a large part of the 20th century. Many of the works on view were bought or commissioned in Mexico by Carl Zigrosser, the director of the Weyhe from 1919 to 1940 and a major advocate of modern Mexican art. After leaving the Weyhe he served as curator of prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 1963.

Americans living in Mexico — including dealers, agents, artists and the American ambassador, Dwight Morrow — joined Zigrosser in championing the modern movement. Among the foreign artists, both American and otherwise, attracted by Mexico’s hospitality, progressivist outlook and cheap cost of living, were Howard Cook, whose rather bland studies of people and customs run to stereotypes; Caroline Durieux, a New Orleanian whose amusing lithograph “Dancing With Vigor” (1932), showing a svelte blonde partnered by a sleekly wolfish Mexican man, proves that comedy could infiltrate the movement; and Jean Charlot, a French-born American and a somewhat weightier contributor to Mexican art.

Charlot’s “Great Builders II” (1929-30) is a large lithograph made after he watched Maya workmen excavate the sacred city of Chichén Itza in the Yucatán, portraying them with exaggerated Maya features as they swarm over the ruins, heirs to the brilliant civilization that flourished in the first millennium. Among his other benefactions, he introduced Mexican artists to the woodcut.

The many lesser-known but worthy talents on hand include Alfredo Zalce, Francisco Dosamantes, Isidoro Ocampo, Jesús Escobedo, José Chávez Morado and Emilio Amero. Absorbing on its own, “Mexico and Modern Printmaking” also makes an illuminating companion show to “Tesoros/Treasures/Tesouros: The Arts in Latin America, 1492-1820” at the museum through Dec. 31. It’s a double bill worth quality time.

“Mexico and Modern Printmaking: A Revolution in the Graphic Arts, 1920-1950” is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Benjamin Franklin Parkway at 26th Street, Philadelphia; (215) 763-8100, philamuseum.org, through Jan. 14. |