|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | March 2007 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | March 2007

Thoughtful Wanderings of a Man With a Can

Holland Cotter - NYTimes Holland Cotter - NYTimes

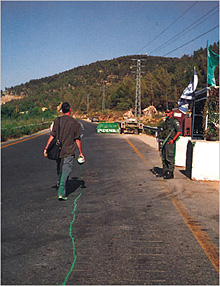

| | Francis Al˙s on his walk through Jerusalem in 2005, in which he retraced the Green Line with a leaky paint can, part of an exhibition at the David Zwirner gallery in Chelsea. (David Zwirner - New York) |

“Sometimes Doing Something Poetic Can Become Political, and Sometimes Doing Something Political Can Become Poetic” is a very long title for an exhibition. But it’s perfect for Francis Al˙s’s show at David Zwirner, his first Manhattan gallery solo in a decade. And it captures in a nutshell the thinking behind some of the most interesting art today.

Mr. Al˙s, who was born in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1959 and has lived in Mexico City for almost 20 years, trained as an engineer and architect. He makes paintings, sculptures and films, but his primary art medium is a form of performance art, an art of symbolic gesture, a kind of acted-out metaphor, produced by a body or bodies in motion, often his own.

One day in the early 1990s he pushed a large block of ice through the streets of Mexico City for nine hours until it had completely melted, a kooky endurance test that was also a meditation on the transience of art and a sly comment on Minimalist sculpture’s space-hogging pretensions.

For a piece called “When Faith Moves Mountains” he assembled 500 volunteers with shovels in a desertlike area near Lima, Peru, and had them move a sand dune four inches. The ritualized toil was about the urgency and futility of labor, labor that makes the pyramids of Egypt monuments not to the pharaohs who commissioned them but to the nameless men who built them.

In the late 1990s, in a piece called “The Loop,” his sense of the heroically absurd became more topical. He was asked to contribute work to a show taking place simultaneously in Tijuana and San Diego. But rather than cross the United States border, a barrier used to keep Mexicans out, he flew from Tijuana to Chile, then to Australia, Hong Kong, Anchorage, Vancouver, Los Angeles and, finally, San Diego. The detour took five weeks but — and this was the point — entailed none of the dangers risked by illegal Mexican migrants trying to cross directly.

His project at Zwirner focuses on another border. In June 2005 Mr. Al˙s walked from one end of Jerusalem to the other carrying a can filled with green paint. The bottom of the can was perforated with a small hole, so the paint dripped out as a continuous squiggly line on the ground as he walked.

The route he followed was one drawn in green on a map as part of the armistice after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, indicating land under the control of the new state of Israel. The original Green Line has since been considerably altered on the ground, with cataclysmic consequences for people on both sides.

Mr. Al˙s restricted his walking to a 15-mile stretch through a divided Jerusalem, a hike that took him down streets, through yards and parks, and over rocky abandoned terrain. In a film of the walk made with Julien Devaux, he seems to attract little notice. People just go about their lives. Even Israeli soldiers at checkpoints barely acknowledge the lanky guy in jeans with a leaky can.

In part this is because — as is always true with Mr. Al˙s’s oblique work, which bows to artists like Joseph Beuys and Gordon Matta-Clark — what he’s really doing isn’t immediately obvious: creating a metaphor about history with his body. As he moves along, dribbling paint, he recreates a barrier that exists in physical form, as a series of concrete partitions separating Israelis and Palestinians, and as a separatist symbol, both triumphant and oppressive.

Mr. Al˙s takes no political position on this; he merely points it out. In a show that blurs distinctions between art and documentation, he includes the film of his walk, archival matter on the original Green Line and interviews he taped with contemporary Israeli, Palestinian and European pundits. (The interviews are also compiled as an exhibition catalog.) The only art in conventional form is a series of funky little sculptural guns, which he made in collaboration with the artist Angel Toxqui from found material in Mexico City.

But his position is, of course, not neutral. The Green Line, as Mr. Al˙s reinscribes it, is radically fluid: the next rainstorm, some traffic, a crowd of passing feet would, and surely did, obliterate it. His version of checkpoint guns are toys. The people he interviews mostly speak from the political left and are critical of the existing partition.

The installation as a whole, like so much of Mr. Al˙s’s work, is incisively worldly and materially ungraspable: a compilation of documentary material that gains unity in the mind as a lasting afterglow. With much new art all too graspable, too clearly designed to adorn hedge-fund homes and museums, artists like Mr. Al˙s are acting like a counterweight, connecting art to the larger world.

The following questions appear in capital letters on one wall of the gallery: “Can an artistic intervention truly bring about an unforeseen way of thinking? Can an absurd act provoke a transgression that makes you abandon the standard assumptions on the sources of conflict? Can those kinds of artistic acts bring about the possibility of change?”

The very long title of Mr. Al˙s’s exhibition boils down to a short, provisional reply: Sometimes, maybe, yes.

“Sometimes Doing Something Poetic Can Become Political, and Sometimes Doing Something Political Can Become Poetic” is on view through Saturday at the David Zwirner gallery, 519 West 19th Street, Chelsea; (212) 727-2070. |

| |

|