|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | March 2007 Entertainment | Books | March 2007

The Irish Soldiers of Mexico, Part 2

Michael Hogan - Freedom Daily Michael Hogan - Freedom Daily

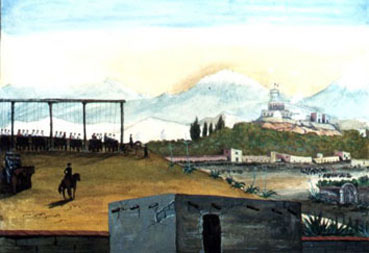

| | Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec (Sam Chamberlain, c1867) |

Most of those who had settled in America in the 18th and early 19th centuries had no real sense of national identity. Those in Virginia considered themselves Virginians, those in Texas, Texans or “Texicans,” and those from Maine, “Down Easters.”

Allegiances were territorial rather than nationalistic. When the victorious American army finally entered Mexico City they played three “national” anthems: “Hail Columbia,” “Yankee Doodle,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

But while there was no clear sense of nationhood, Americans were nevertheless in the process of defining who they were. And they did this essentially by stating quite clearly what an American was not. In the 1840s he was not a “Negro,” not a Mexican, not an Indian, and certainly not an Irish Catholic. Notes Dale T. Knobel, professor of history at Texas A&M:

The Irish would be seen increasingly as set apart by visible conduct and appearance. This development coincided with national self-satisfaction that accompanied the working out of the United States Manifest Destiny through geographical expansion.

Manifest Destiny was another aspect of Calvinist belief. It held simply that the Anglo-American was predestined by God to inherit the entire American continent. Beginning with the “noble experiment” in New Jerusalem (Salem, Massachusetts), the “City on the Hill,” this new breed would spread over the entire land mass of the Americas, displacing indigenous people, and buying out or running off French and Spanish landholders on their inevitable march of progress.

The inheritors of Manifest Destiny, it must be remembered, were white Anglo-Protestants, and they took steps to ensure that the distinctions between them and others, whether religious or racial or quasi scientific, were constantly emphasized to prove that they were deserving of this gift. Wrote one newspaper editor:

We are believers in the superintendence of a directing Providence, and when we contemplate the rise and amazing progress of the United States, the nature of our government, the character of our people, and the occurrence of unforeseen events, all tending to one great accomplishment, we are impressed with a conviction that the decree is made, and in the process of execution, that this continent is to be but one nation.

Even the highly respected Ralph Waldo Emerson would write that:

...men gladly hear of the power of blood or race. Everybody likes to know that his advantages cannot be attributed to air, soil, sea, or to local wealth, as mines or quarries, nor to law and tradition nor to fortune, but to a superior brain, as it makes it more personal to him.

The Scourgings, Brandings, and Hangings

In September 1847, the Americans put the Irish soldiers captured at the Battle of Churubusco on trial. Forty-eight were sentenced to death by hanging. Those who had deserted before the declaration of war were sentenced to whipping at the stake, branding, and hard labor. Most American historians contend that the punishments were neither particularly brutal nor unusual given the fact that there was no prescribed code.

However, clear documentation exists that the codified Articles of War (1821) and William De Hart’s Observations on Military Law, and the Constitution and the Practice of Courts-Martial (1847) governed courts-martial at that time and clearly stipulated the exact punishments these soldiers should have received. The Articles of War stipulated that the penalty for desertion and/or defecting to the enemy during a time of war was death by firing squad. Hanging was reserved only for spies (without uniform) and for “atrocities against civilians.” Nevertheless, 48 of the San Patricios were hanged, 18 in San Angel and 30 in a place called Mixcoac.

Desertion before a declaration of war was punishable by one of the following punishments: branding on the hip in indelible ink, 50 lashes, or incarceration at hard labor. However, the San Patricios received more than 50 lashes, “until their backs had the appearance of raw beef, the blood oozing from every stripe,” according to one American witness. In addition, the punishment was administered by Mexican muleteers who were threatened with the same lash if they did not “lay it on with a will.” These same Irishmen were also branded with “D” for deserter on the cheek by a red-hot branding iron, and they were sentenced to imprisonment and hard labor.

The sentence of the court, according to the Articles of War, should always be carried out promptly. “To prolong the punishment beyond the usual time would be highly improper, and subject the officer who authorized or caused such to be done to charges.” In the case of the last of group of 30 San Patricios to be hanged, this Article of War was cavalierly ignored.

The Hangings by Colonel Harney

General Winfield Scott had chosen an officer who had been twice disciplined for insubordination as his executioner of the last group of 30 San Patricios. Colonel William Harney had been soldiering for almost 30 years and was notorious for his brutality. During the Indian Wars he was charged with raping Indian girls at night and then hanging them the next morning after he had taken his pleasure. In St. Louis, Missouri, he was indicted by a civilian court for the brutal beating of a female slave that resulted in her death. The choice of Harney as executioner of the San Patricios seemed calculated by the American high command to inflict brutal reprisals on the Irish Catholic soldiers. Harney would not disappoint them.

At dawn on September 13, 1847, some days after the first group of 18 had been executed, Harney ordered the remaining San Patricios to be brought to a hill in Mixcoac a few kilometers from Chapultepec Castle where the final battle of the war was to be fought. Observing that only 29 of the 30 prisoners were present, Harney asked about the missing man. The army surgeon informed the colonel that the absent San Patricio had lost both his legs in battle. Harney, in a rage, replied, “Bring the damned son of a bitch out! My order was to hang 30 and by God I’ll do it!”

After the guards dragged Francis O’Conner out and propped him up on his bloody stumps, nooses were placed around the necks of each of the men, and they were stood on wagons. Harney then pointed to Chapultepec Castle in the distance and told the prisoners that they would not be hanged until the American flag was raised over the castle signifying that the Yankees had won the battle. The prisoners yelled out in incredulity and protest. Some made jokes and sarcastic remarks trying to goad the unstable colonel into giving an impulsive order. One prisoner asked Harney to take his pipe out of his pocket so that he might have one last smoke. Then, with a glint in his eye, he asked if the colonel would not mind lighting it with his “elegant hair.”

The redheaded Harney did not appreciate the joke. He drew his sword and struck the bound prisoner in the mouth with the hilt, breaking several of the man’s teeth. The prisoner was not intimidated, however. Spitting out blood and broken teeth, the irrepressible Irishman quipped, “Bad luck to ye! Ye have spoilt my smoking entirely! I shan’t be able to have a pipe in my mouth as long as I live.”

Meanwhile the Battle of Chapultepec raged on. Finally, at 9:30 a.m. the Americans scaled the walls of the castle, tore down the Mexican flag, and raised the Stars and Stripes. With that, Harney drew his sword and, “with as much sangfroid as a military martinet could put on,” gave the order for execution. The San Patricios, after four and a half hours of standing bound and noosed in the 90-degree sun, were finally “launched into eternity.”

Harney’s violation of the Articles of War requiring prompt execution did not result in charges being brought against him. Rather, his behavior was rewarded. A month later Harney was promoted to brigadier general and accompanied the commander in chief in a triumphal march in Mexico City.

The punishments ordered for the San Patricios and the way they were carried out conveyed more than the mere judgment of the court. They were clear examples of religious and racist reprisals. In spite of the fact that more than 5,000 U.S. soldiers deserted during the Mexican War, only the San Patricios were so punished, and only the San Patricios were hanged.

The Conquest of Mexico and Celtic-Americanism

Fueled by Manifest Destiny and its concomitant racial and religious animosity, the American government dictated terms to the Mexicans in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. More than two-thirds of the Mexican Territory was taken, one-half if one included Texas, and out of it the United States would carve California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Wyoming, and parts of Kansas and Colorado. It was a profitable American adventure, a conquest to put Napoleon to shame, and all done in the name of democracy and Manifest Destiny.

Among all the major wars fought by the United States, the Mexican War is the least discussed in the classroom, the least written about, and the least known by the general public. Yet, it added more to the national treasury and to the land mass of the United States than all other wars combined.

After the conflict, so much new area was opened up, so many things had been accomplished, that a mood of self-congregation and enthusiasm took root in the United States. The deserters from the war were soon forgotten as they homesteaded and labored in the gold fields of California or, as the 1860s approached, put on the gray uniform of the Confederacy or the blue of the Union. Prejudice against the Irish waned, as the country was provided with a “pressure valve” to release many of its new immigrants westward.

As Irish veterans returned from the Civil War and gained political power, they were increasingly seen as a branch of the white race (Celtic American) by the so-called scientific theorists who had previously denied them that privilege. Irish in the United States, anxious to be assimilated, gladly accepted the new designation.

Ironically, the American Irish would be among the first to disassociate themselves from the San Patricios and promote the notion that it was not an Irish battalion at all! Moreover, anti-Catholic prejudice would so diminish that by 1960 an Irish Catholic would be elected president of the United States. The Soldiers of St. Patrick would disappear from the annals of U.S. history, an embarrassing reminder of a less-tolerant era in our Republic.

Commemorations

Each year commemorations are held in San Angel in Mexico to honor the Irish who died in the war. A marble plaque in the town square reads, “In Memory of the Irish Soldiers of the Heroic Battalion of San Patrick Who Gave Their Lives for the Mexican Cause During the Unjust North American Invasion of 1847,” followed by the names of 71 of the men. A color guard of crack Mexican troops marches forward with the Mexican and Irish colors to a spine-jarring flourish of drums and bugles. The “Himno Nacional” is then played, followed by “The Soldier’s Song.” Students and dignitaries place floral tributes on the paving stones, and an honor roll is called of the fallen soldiers as the crowd collectively chants after each name, “Murió por la patria!” (He died for the country!) In Clifden, County Galway, the birthplace of John Riley, a similar ceremony is held each September 13.

For most Mexicans, solidarity with the Irish is part of a long tradition. There is in both countries an emphasis on the spiritual center in the family and a non-materialistic viewpoint whereby a person’s worth is determined not by what he owns but by the quality of his life. And if Paddy and Bridget, like José and María, were considered incapable of being assimilated into Anglo Protestant society, their acceptance into Mexican society was seamless. In the words of John Riley, written in 1847 but equally true today, “A more hospitable and friendly people than the Mexican there exists not on the face of the earth ... especially to an Irishman and a Catholic.”

Riley sums up what cannot be clearly documented in any history: the basic, gut-level affinity the Irishman had then, and still has today, for Mexico and its people. The decisions of the men who joined the San Patricios were probably not well-planned or thought out. They were impulsive and emotional, like many of Ireland’s own rebellions — including the Easter Uprising of 1916. Nevertheless, the courage of the San Patricios, their loyalty to their new cause, and their unquestioned bravery forged an indelible seal of honor on their sacrifice.

Michael Hogan is the author of 14 books, including The Irish Soldiers of Mexico, which was the basis for two documentary films and an MGM release titled One Man’s Hero, starring Tom Berenger and Daniela Romo. He is the head of the humanities department at the American School of Guadalajara and historical consultant to the Irish Embassy in Mexico. Send him email at mhogan@infosel.net.mx |

| |

|