|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | April 2007 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | April 2007

The Great Mexican Art of Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo

Dr Sunil K Sukumaran - Diplomatist Dr Sunil K Sukumaran - Diplomatist

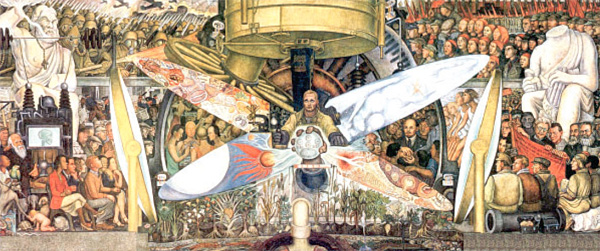

| Diego Rivera is perhaps best known for his 1933 mural, Man at the Crossroads, in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Centre, which was destroyed by Rockefeller’s staff. He repainted the work in 1934 in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. This version was called Man, Controller of the Universe (above).

|

The year 2007 marks the 50th death anniversary of one of the most prominent artists of the last century - Diego María Rivera. Rivera’s legacy to modern Mexican art is decisive in his murals and his canvases, and he gained international acclaim as a leader of the Mexican mural movement. Rivera took his art to the public, to the streets and buildings, always managing a precise, direct, and realist style, but full of social content. Featuring stylised representations of the working classes and indigenous cultures, and espousing revolutionary ideals in his murals of the 1920s and 1930s, Rivera developed a new, modern imagery expressing Mexican national identity. Essentially famous as a muralist, Rivera ranks among the great artists of the 20th Century.

Born in Guanajuato, Mexico, in 1886, Rivera moved with his family to Mexico City in the early 1890s. His prodigious talent was recognized at an early age, and by the age of twelve, he enrolled in the national school of fine arts. Upon completion of his degree, the Mexican government awarded a stipend to Rivera to further his career in art by travelling to Europe, and he left for Spain in early 1907. Remaining in Madrid for more than two years, Rivera studied with the Spanish academic painter Eduardo Chicharro, while assiduously copying from the collections of the Museo del Prado, and over time became part of the city’s bohemian avant-garde. Rivera then embarked on an itinerary of art study in Europe that included visits to Paris, London, and Belgium.

In Bruges, he met the Russian painter Angelina Beloff, who soon became his companion and common-law wife, and together they moved to Paris. (The two remained a couple until Rivera departed for Mexico in 1921. He married Frida Kahlo in 1929.) During his time in Europe, Rivera drew upon the radical innovations of cubism, launched a few years earlier by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Rivera adopted their dramatic fracturing of form, use of multiple perspective points, and flattening of the picture plane, and also borrowed favourite cubist motifs, such as liqueur bottles, musical instruments, and painted wood grain. As his close friend and the subject of Portrait of Martín Luis Guzmán wrote that Rivera “arrived calmly and late” to cubism.

Yet, Rivera’s cubism is formally and thematically distinctive - characterized by brighter colours and a larger scale than many early cubist works; his work also features highly textured surfaces executed in a variety of techniques. Many of his paintings produced during a period that coincided with both the Mexican Revolution and World War I reflect Rivera’s expatriate role and explore issues of national identity and carry nationalistic overtones. Many also incorporate souvenirs of Mexico from afar and are infused with revolutionary sympathy and nostalgia.

The references to his native land are often embedded within canvases that refer to new Spanish, French, or Russian allegiances. Serapes, the woven blankets worn by Mexican peasants, became a hallmark of the artist’s cubist paintings. They are employed to powerful effect in the 1914 portrait of sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, where their vivid patterns vitalize the composition and cloak his Lithuanian friend in Rivera’s Mexican identity.

Rivera returned to Mexico for a one-man exhibition of his work that opened on 20 November 1910, a date notorious for its association with the start of the Mexican Revolution. Shortly after the close of his exhibition a month later, Rivera again departed for Europe; it would now be more than a decade - and following the end of the Revolution - before he returned to Mexico. Rivera painted several significant works in USA. From 1930 to 1933 he completed a number of frescoes in the US, mostly consisting of industrial life.

Diego is perhaps best known by the public world for his 1933 mural, Man at the Crossroads, in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Centre. When his patron Nelson Rockefeller discovered that the mural included a portrait of Lenin and other communist imagery, he fired Rivera, and the unfinished work was eventually destroyed by Rockefeller’s staff. As a result of the negative publicity, a further commission to paint a mural for an exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair was cancelled.

In December 1933, an angry and humiliated Rivera returned to Mexico. He repainted the work in 1934 in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. This version was called Man, Controller of the Universe. On 05 June 1940 Rivera returned for the last time to the United States to paint a ten panel mural for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. Pan American Unity was unveiled 29 November 1940. The mural and its archives reside at City College of San Francisco. Perhaps, his finest surviving work in the US is the Detroit Industry - 27 fresco panels on the walls of an inner court at the Detroit Institute of Arts that he painted in 1932.

Frida Kahlo

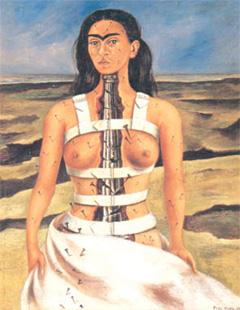

| | The Broken Column is, perhaps, the painting that best shows the extreme pain Frida Kahlo had to endure. |

This year also celebrates the 100th birth anniversary of Frida Kahlo - the famous Mexican painter who depicted the indigenous cultures of her country in a style combining realism, symbolism, and surrealism - the wife of Diego Rivera.

Drawing on personal experiences (she contracted polio at the age of six and suffered near fatal injuries that included a broken spinal column in a vehicular accident when she was nineteen) including her troubled marriage, her painful miscarriages, and her numerous operations, Kahlo’s works are often characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Out of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits that frequently incorporate symbolic portrayals of her physical and psychological wounds.

Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in the bright colours and dramatic symbolism found in her paintings. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work as well; she combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition - which were often bloody and violent - with surrealist renderings.

The Broken Column is, perhaps, the painting that shows to the fullest the extreme pain she had to endure. The column itself, which is broken, shows one of the sources of her pain, the nails in her body show in a physical way the pain she had to bear, and the tears in Frida’s eyes reflect the excruciating suffering.

However, Frida’s face shows both courage and resignation, and Frida’s nudity, in a way, suggests that she felt she could do very little about her situation. But, in spite of all her agony, Frida kept on expressing and surpassing herself by creating outstanding paintings during her lifetime. |

| |

|