|

|

|

Entertainment | April 2007 Entertainment | April 2007

'In the Pit': A Labored Look at Working Men

Philip Kennicott - Washington Post Philip Kennicott - Washington Post

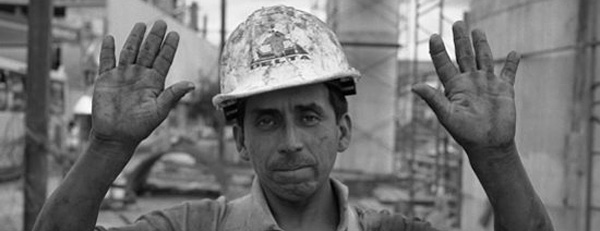

| A scene from Juan Carlos Rulfo's documentary "En El Hoyo" ("In The Pit,") which won the top prize in the Documentary Feature Competition at the Miami International Film Festival. Photo courtesy of the festival.

|

Juan Carlos Rulfo's documentary "In the Pit" is made in the currently fashionable mode, without voice-over and heavily edited into a fluent, seemingly intimate portrait of its subjects - in this case, the men building a huge elevated highway over Mexico City's notoriously traffic-clogged streets.

Their comments about life, love, politics and God are spliced together into a flowing poetry of mostly banal but definitely sincere observations. An intriguing soundtrack, by turns suggestive of a circus calliope and space-age electronica, gives it an edgy feel. There are brief interludes in which the cars and the workers are sped up into a blur reminiscent of the Godfrey Reggio films for which Philip Glass famously provided his liquid soundtracks. And there is a recurring character, a superstitious woman with Cassandra tendencies who feels quite certain that there are souls embedded in the towers that support the new highway, as if it were a latter-day Great Pyramid with an insatiable maw for human lives.

But nothing much happens. The ominous predictions of death, the portentous atmosphere, don't go anywhere. Mostly the men banter in the timeworn, misogynistic and homophobic vernacular that is more openly expressed and casually indulged by the working class the world over. The director seems intent that you like them, but it's not always easy. They beat their wives and discuss their ambitions, or lack of them. They talk of getting wasted on drink and drugs, backslap each other, insult each other, josh and joke, and generally coexist in the nervous, affectionate but not too affectionate way of men deeply uncomfortable with intimacy.

They're doing hard, dirty and dangerous work, and the rich people with cars who will use their highway probably never give the men a second thought. But Rulfo's effort to humanize them is overwhelmed by his own artiness. There is something almost offensive about the documentarian's presumption of getting at the inner truth of these men, and then jazzing it up into a cinematic tone poem. He may very well have set out to make a film with pretensions of working class authenticity; in fact, he made a classic case of decadent art.

Perhaps the men themselves are to blame for the film's emotionally inert qualities. More than 40 years ago, in his classic "The Labyrinth of Solitude," the Mexican Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz wrote, "To confide in others is to dispossess oneself; when we have confided in someone who is not worthy of it, we say, 'I sold myself to So-and-so.' " One wonders if the men, despite the film's advertising of its intimacy with them, in fact were intentionally eluding the filmmaker.

Rulfo should have considered using what so many trendy directors forsake: succinct voice-over and talking heads to put the serious issues (urban poverty, urban stress, environmental degradation, corruption) into perspective. But like the highway these men are building, Rulfo's film sails above the larger context that would actually bring emotional meaning to the lives he wants to celebrate. |

| |

|