|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | April 2007 Entertainment | Books | April 2007

Mexican Poets on a Wild Quest

Vinnie Wilhelm - SFGate.com Vinnie Wilhelm - SFGate.com

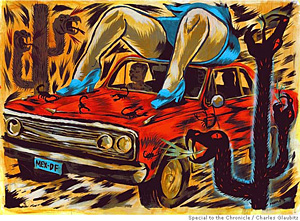

| Mexican poets on a wild quest: Terror lurks below surface of sprawling epic as dozens of narrators build a funny, unsettling universe. (Charles Glaubitz/Chronicle)

The Savage Detectives

Roberto Bolaño; translated by Natasha Wimmer

Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 577 Pages; $27 |

When he died in Barcelona at 50 in 2003, the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño was already a legend in the Spanish-speaking world - the most important writer to emerge from Latin America since García Márquez, and the voice of a generation devastated by war and the ascendance of oppressive dictatorships across the region.

When I began reading "The Savage Detectives" last month, I had already devoured the first three of Bolaño's books to arrive in English - two short novels, "By Night in Chile" and "Distant Star," and the story collection "Last Evenings on Earth" - and become a devoted fan. But I was still unprepared for "The Savage Detectives," the work that made his reputation when it first appeared in 1998, and for which he was awarded the Rómulo Gallegos Prize.

Available now in a seamless translation by Natasha Wimmer, this novel is an utterly unique achievement - a modern epic rich in character and event, suffused in every sentence with Bolaño's unsettling mix of precision and mystery. It's a lens through which the strange becomes ordinary and the ordinary is often very strange.

"The Savage Detectives" is ostensibly about a group of avant-garde poets in Mexico City in the mid-1970s, the so-called visceral realists, who have taken the name of another obscure avant-garde Mexican poetry movement from the 1920s. The tenets of visceral realism remain vague; its followers are young, broadly leftist and anti-establishment. They don't like Octavio Paz, and may or may not be planning to kidnap him.

In the predawn hours of New Year's Day 1976, the group's enigmatic leaders, Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, leave the capital in a borrowed Chevy Impala, heading north into the Sonoran Desert on a quest to find the lost mother of visceral realism, Cesárea Tinajero, who disappeared there 40 years before. Belano and Lima are accompanied by a hooker named Lupe and the teenage visceral realist poet Juan García Madero; they are pursued by a murderous pimp.

That's how it starts. From there the plot swings around and smashes itself to pieces, to borrow a phrase of Bolaño's. The book's opening section, which takes us up to the Impala's flight from Mexico City, is narrated by García Madero, and we return to his narration at the end of the novel for the denouement in Sonora. In between lies a 400-page assemblage of monologues, varying in length from a single, short paragraph to upward of 20 pages, delivered by the disparate cast of characters Belano and Lima encounter in 20 years of vagabond wandering after they leave Mexico in 1976.

The monologues are presented as interviews conducted by an unnamed detective or detectives, for an unstated purpose, and the story they trace covers a lot of ground. This is a novel set in Mexico City, Oaxaca, Tlaxcala, Managua, Barcelona, Roussillon, Paris, Rome, Vienna, Tel Aviv, Los Angeles, New York, Luanda, Kigali and the war-torn countryside of Liberia, among other locations. It is a novel that features no fewer than 54 first-person narrators (I counted), who speak to us from parks and libraries, bars and dark apartments, from inside lunatic asylums, and from the hospitals in which they are dying. Many of them are poets, many are Latin American exiles and almost all are living in some kind of desperation on the margins of the late 20th century.

If you or I - or anyone but Bolaño, I suspect - tried to structure a book in this way, the inevitable result would be chaotic fragmentation. Belano and Lima remain opaque, and there is no central plot in the traditional sense. Each of the narrators is really telling his or her own story, and it works in part because each one is so compelling. But what ultimately holds "The Savage Detectives" together is the strength of Bolaño's vision. What all the characters share is a sense of instability and terror lurking just beneath the surface, a pervasive disquiet that drives the prose. Bolaño's is a world in which the door of an otherwise innocuous Mexico City bus shuts tight "like the door of a crematorium oven," and a junior editor, trying to hawk a poetry anthology to his boss, has "the kind of laugh you hear when you're walking down the deserted corridors of a hospital." The people in this book are haunted, bewildered and, often, hilarious. They say things such as, "At night I wake up screaming. I dream about a woman with the head of a cow. Its eyes stare at me. With touching sadness, actually." The unexpected turns in Bolaño's prose always seem to reveal a hidden threat; they afford pleasure on every page, but also give the novel its disturbing emotional force.

Consider the following account, offered by one former visceral realist about the funeral of another:

"Of his old friends, I was the only one who went to his burial, in one of the patchwork cemeteries on the north side of the city. I didn't see any poets, ex-lovers, or editors of literary magazines. ... Before I left the cemetery, two teenagers came up to me and tried to lead me somewhere. I thought they were going to rape me. Only then did I feel rage and pain at Ernesto's death. I pulled a switchblade out of my purse and said: I'll kill you, you little creeps. They went running and I chased them for a while down two or three cemetery streets. When I finally stopped, another funeral procession appeared. I put the knife in my bag and watched as they lifted the coffin into its niche, very carefully. I think it was a child. But I couldn't say for sure. Then I left the cemetery and went to have drinks with a friend at a bar downtown."

Bolaño's characters are never far from the specter of violence, a fundamental reality for Latin Americans born in the 1950s. Bolaño himself was briefly imprisoned in Chile after the CIA-backed Pinochet coup in 1973. He called "The Savage Detectives" "a love letter to my generation," and it is a moving composite of the Latin American diaspora in the turbulent years about which he writes, as well as a reminder that novelists will always be our best historians.

But this book is also a dark prophecy for the modern world, which seems more like Bolaño's every day.

Vinnie Wilhelm is a writer in Connecticut. |

| |

|