|

|

|

Vallarta Living | May 2007 Vallarta Living | May 2007

One Life at a Time

Pete Dybdahl - Roanoke Times Pete Dybdahl - Roanoke Times

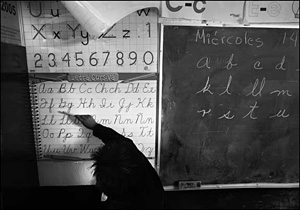

| | Gustavo Jeronimo Herrera practices his alphabet at primary school in Guadalajara. Thanks to his participation in CODENI he attends school and stays off the street during the day. (Josh Meltzer/Roanoke Times) |

Guadalajara, Mexico - The trouble started the week before, when Felipe got beaten up after school. The following Tuesday night, he didn't come home at all.

Wednesday morning, Felipe arrived home intact. By the time Danielle Strickland got to his house, Felipe's mother and a crowd of aunts stood around him anxiously.

"Where were you?"

"Where'd you stay?"

"With a girlfriend?" a male cousin called out.

Felipe stared at the floor. He is 15, skillful at soccer and the first in the family to go to middle school. His hair was gelled straight up, like a cartoon character that had stuck his finger in a socket. Felipe bears the hopes of his family.

Strickland is a Roanoke native who's easily the only American woman for a mile around. She punched him on the arm. Felipe's grandmother sat over a simple gas stove, stirring a pot of guavas. The women were silent, then they wept.

Why didn't he call? Why didn't he stay with his aunt downtown? Should he change schools? Occasionally, the women switched from Spanish to Otomi, a native language.

"What do you think, Felipe?" one aunt asked. "Was it good what you did last night?"

"No," he said without looking up.

"What do you think?" the aunt asked Strickland.

"Did you learn something?" Strickland asked him.

She passed him a card with her phone number. As is her policy, she was careful not to punish. "I'm not a mom," she said on her way out that morning.

She is more like a big sister and teacher and social worker. Strickland - who helps dozens of children like Felipe with their homework and works to give them a proper childhood - is the focus of this story.

A street situation

Strickland, 26, has a few Mexican nicknames. There's Skinny, or sometimes Güera, slang for a light-skinned person.

But when she takes her seat at a knee-high table in a library downtown, she is Maira - the Mexican term for a companion-educator.

With Tomas Trinidad (nickname: Chubby), a friend and fellow Mairo, she runs an after-school program for about 75 kids, kindergartners to middle schoolers, who would otherwise spend another evening on the street.

Together, they direct a Mexican nonprofit group called CODENI, an acronym that translates to Children's Rights Collective. CODENI's office runs out of the front two rooms in Strickland's house.

A framed sign gives the group's mission in Spanish: "... to defend and extend the rights of girls and boys, through education, investigation and defense."

On a recent Monday afternoon, these children gathered around Strickland with reading assignments and math homework. A few struggled to use their library voices.

"Nine minus zero," a first-grader named Ismael cried in Spanish.

"Nine minus zero is the easiest of all," Strickland said gently.

In the library's open-air vestibule, a large group of children sat with Trinidad making bracelets. In the busy square in front, they skipped rope and kicked a soccer ball.

The children live in cinder block houses outside the city and in rented rooms downtown. They wear simple school uniforms or hand-me-downs. They spend hours around sidewalks and plazas while their parents sell flowers and potato chips for pesos.

They are, as Strickland says, in a "street situation."

To be poor and a child in Mexico's second-largest city carries a list of obligations: To work at an early age, to skip your birthday, to hope only for small things.

Many perils surround them: a shoeshiner dealing drugs, older boys who huff aerosol, prostitutes, sometimes combative alcoholics.

At the end of February, Trinidad left his job working at a refuge for teenage boys who live on the street to devote more time to the after-school program. The boys he worked with were some of the hardest cases: drug users, prostitutes, some sick with the diseases that follow.

Strickland is more optimistic about the younger children she helps. The after-school sessions balance the pressures of an afternoon on the street and urge them toward a better life, she says.

"Our work is preventive," she says. "We want these kids to continue with an education to escape poverty."

Hill of the Stain

Sometimes, after a few beers with friends, Strickland will share her dreams for Guadalajara: An army of street educators helping all the children with their long division and keeping them safe.

But during the workweek, victories are often smaller.

Early one morning, Strickland left downtown, turned off a paved road and drove through one of the city's poorest neighborhoods.

Tourists do not visit Cerro del Cuatro, or Hill of the Four. The houses are small, cinder block rectangles. Many of the roads are unpaved. This morning, plastic bottles, pulped orange halves and a man's plaid shirt littered the street. Some people in Guadalajara refer to the neighborhood as the Hill of the Stain.

Strickland's first trip here was last spring. She was embarrassed when, getting directions, she asked what color the house was. "None of the houses are painted," she said.

Driving up the hill, with a bagel in her lap and Trinidad in the passenger seat, she added, "I'm hesitant to call it a shantytown. They have a great view."

Strickland parked outside a house and put a lock on the steering wheel. She and Trinidad climbed out. They joined six kids from their after-school program on their walk to Mexican Heroes Elementary School.

Inside the school's graffiti-scrawled walls, students lined up as "The March of Zacatecas" played over the loudspeaker. In unison, they greeted the morning with "Buenos días." After the first class, a first-grade teacher came out to talk with Strickland and Trinidad about Tonito, a student they have in common.

"Tonito's clever," the teacher, a middle-aged woman in a bright floral dress, said. "But he doesn't have much desire." She continued: His grandmother pushes him, but his mother indulges him.

Later that day, Strickland said, "We should look into it."

Strickland and Trinidad walked outside and sat down.

In a dusty field nearby, a group of boys chased a soccer ball, while a group of girls watched. The gym teacher, a man in blue athletic pants, whistled for a foul.

"Why don't you let the girls play?" Trinidad called to the gym teacher.

"They don't want to play," the gym teacher said.

"Yes we do!" one girl shouted.

"Why didn't you tell me?" the gym teacher said. "We'll play to two goals."

After two goals, the girls took the field.

That morning, President Bush met with the Mexican president to discuss immigration. At nearby beaches, thousands of college students were waking up to find that spring break was half over. And Strickland said to Trinidad, "You changed gym class."

A Third-World introduction

When Strickland talks about what she does, she says it's a calling. She sees a need and knows she can fill it. Then she tells the story about Cancun.

When she was 9, her parents took Strickland and her brother and sister to Cancun. For a day trip, they rented a car and left the city.

At an intersection, children her age approached the car with dirty newspapers, offering to clean the windshield for pesos. She saw simple houses, no power lines. It was her introduction to poverty.

The summer after her sophomore year at Patrick Henry High School, Strickland left Roanoke for two months in rural Costa Rica.

"It was total culture shock. I got there, and I was a party girl. I worked at the Gap at the time," she said. She spent the first weeks listening to her compact disc player and writing in her journal. She adapted to her host family and their farm.

In college, she spent a year in Latin America: first a semester in Guadalajara, the second in Ecuador. Strickland, who was a baby sitter and regular volunteer in her church's nursery, was drawn to street kids. She wrote her senior thesis on street education.

She graduated from college in 2002 and was back in Guadalajara by the fall. Eventually, she found work teaching high school English at the city's German School - a job she still has. It provides her with a small salary (about $1,000 a month after taxes) and a visa to stay in Mexico.

In 2004, after working with street kids through a city agency, she joined CODENI. She began an afternoon class right on the streets, and eight kids showed up. By August, her program had grown to 30 and found a home in the University of Guadalajara's library.

Strickland planned to cap the group at 50, but by mid-March the program had an enrollment of 77, with a waiting list.

"Being that we're on the street, we can't really close the door," she said.

'It's never too late'

After leaving Mexican Heroes Elementary School, Strickland and Trinidad stopped at Felipe's house. That's when they found the anxious female relatives wanting to know where the teen had been the night before.

Men in Felipe's family are rare. In August 1999, an aunt died, and the family loaded onto a pickup truck to drive to their hometown for her funeral. On the highway, the trailer of a truck they were following disconnected, shearing off the top of the family's pickup.

The crash killed 10 family members, husbands and fathers, including Felipe's father. The family keeps a yellowed copy of the tabloid that covered the accident. Under the headline "TRAGEDIA" several pictures show bodies in the road.

After a crash like that, Trinidad said, "The women take care of the men."

And now Felipe had stayed out all night. He says he and a friend were working on a school project, it got late and the buses stopped running. He didn't have the cellphone number for Aunt Sofia, the only relative with a telephone.

The aunts look skeptical.

The talk turned to the scholarships that CODENI gives its best performers, including Felipe's sister: $270 a year for school supplies and uniforms, plus a little extra for birthday and Christmas gifts - events that many students' parents never celebrated.

"There's no scholarship for people like me," Aunt Sofia said, taking a turn stirring the pot of guavas. She was pregnant and having complications. She had stopped going downtown, and her kids had stopped attending the after-school program.

"There are programs," Strickland offered. "It's never too late."

Strickland and Trinidad accepted a bag of potato chips and drove down the Cerro.

Street economics

Bags of potato chips are a staple of Guadalajara's street economy. Often they're the means by which many of Strickland's students survive.

Tomasa Isidro is a wife and mother of three who has made and sold chips on the street since she was a girl. Her family's livelihood depends upon them.

It works like this: A 130-pound sack of potatoes costs Isidro about $23. Out of season, the price will rise to about $65. Turning a sack into chips takes about six hours of slicing and frying.

A small bag of homemade potato chips, with lime juice and a dash of salsa, costs 10 pesos (a little less than $1). Most days, Isidro earns about $5. Her record is $10.

She does the slicing and frying in a communal open-air kitchen next to the single room where her family lives.

The rent for that room is $60 a month, and with it comes access to a single bathroom shared by about 25 neighbors. Inside the family's room, pictures of the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos cover dirty walls.

One source of unmistakable family pride is Isidro's daughter, Lizbeth, 9. Thanks in large part to CODENI and Strickland, Lizbeth excels at her studies - while Isidro cannot even spell her own husband's name. Talking about Strickland's work with her daughter makes Isidro cry.

But whether or not Isidro will be able to continue her occupation is a question she, Strickland and others have great concern over.

In November, the city began aggressively pursuing unlicensed street vendors. They had to move around, losing their regular customers. Inspectors gave fines close to $200 and confiscated vendors' carts and baskets.

Strickland and others suspect the move was to make the city more attractive for tourists.

"They say 'It's prohibited,' " Rosa Gonzalez, Isidro's cousin and a potato chip vendor, said. "We have worked for 30 years downtown. We're not new."

"When I was 9 I didn't go to school. I sold potato chips. If they don't let us work, we can't send our kids to school," she said.

The vendors who continue to work downtown have become experts at spotting the inspectors. When Isidro or Gonzalez see one, they yell to their sisters and cousins to ándale - take off.

There are stories of inspectors who ask for bribes, who help themselves to what the ladies are selling. But Luis George is not one of them.

One night, George walked slowly through Guadalajara's Aranzazú Garden, sending at least four vendors running across the street with their Styrofoam trays of chips and other snacks.

George appeared to be strolling more than conducting an investigation. His mustache was neatly trimmed and before speaking, he tucked his thumbs into his belt loops.

"If they respect my work, I'll respect theirs," George said of street vendors. As if by magic, Ismael, the son of one of the vendors, appeared and scowled at him. George reached out and patted him on the cheek. Ismael ran away. "Some inspectors think they have to impress the boss by giving a lot of fines."

Strickland had been nearby chatting with vendors and asked if he had a ticket quota. He said he did not. They talked about street life, then Guadalajara.

"I'm leaving for vacation tomorrow," George said before walking off. He said his substitute was named Beto. "He's relaxed, too."

A step further

Thursday evening, CODENI's crew - Strickland, Trinidad and Strickland's longtime boyfriend, Jorge Lamas Mendez, who coordinates the education program - took the subway to the Plaza Universidad, a busy square downtown that's not much larger than the area in front of the Roanoke City Market building.

Outside the library, they greeted each child with a popular handshake: a brush of the palms, a bump of the fists.

With the mothers who came - it's almost never fathers - it was simple handshakes. Pedestrians stared at Strickland, blond-haired and a head taller than many Mexican men, as she chatted with street vendors.

Outside the library, Trinidad passed out pencils and paper.

"We're all going to draw our rights," he said. "Which rights do you remember?"

A right to play, the table said, a right to education.

"I will draw them all," one boy announced.

"OK, good," Trinidad said.

Inside the library, Strickland sat with several boys, including Ismael, who was writing the numbers from zero to 100 by tens.

At other tables, several American volunteers - mostly college students or recent graduates - sat with groups of children. Halfway through the evening, the kids gathered in the square outside the library for a group photo. People walked home from work with bags of groceries, and teenagers sat by an empty fountain sending text messages.

The kids jumped on one another, hammed it up for the camera, gave one another bunny ears.

With each photo they shouted, "Uno, dos, tres, CODENI."

Lamas took the moment to address the kids. "Don't run in the library," he said. The kids turned and ran back to the library.

When they regrouped inside, children huddled around Strickland, chanting Maira to get her attention. She made notes on a grade sheet next to their names.

Strickland hopes these children will go a step further than they would have without someone taking an interest in them. For some, that will be going to college or getting a steady job. For others, that will be learning to read and write.

Ismael looked up from his math work and said, "Ya!" - done.

Strickland glanced at his paper and the empty line at the bottom.

"No," she said. "One more." |

| |

|