|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | July 2007 Travel & Outdoors | July 2007

Batopilas: Mexico's Hidden Shagrila

Kelly Fenstermaker - American-Statesman Kelly Fenstermaker - American-Statesman

go to original

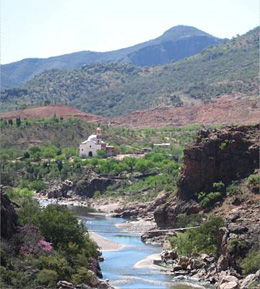

| | The 18th-century Lost Cathedral of Satevo rises up in a desolate valley along Copper Canyon. The cathedral poses many questions about its origins. (A.C. Conrad) |

It's six-thirty in the morning, and Batopilas is waking up. The sun's first rays have tipped the mountains that surround the little Mexican town, coloring them a soft gold. Children walk in the streets on their way to school, the girls dressed in neat pink uniforms. Dogs stretch and abandon door steps where they have spent the night, like sleeping guardians. Residents and shop owners emerge to sweep the narrow cobblestone streets of yesterday's debris.

In the middle of town, a narrow foot bridge spans the Batopilas River that separates the main part of town from a smattering of adobe dwellings attached to a hill on the opposite side. Already, a few inhabitants of the hillside have begun to make their way down steep paths to the bridge and into town.

This was my last day in Batopilas. I had arrived with a tour group of 12, led by Jim Glendinning, author of the guidebook, "Adventures of the Big Bend." He leads small, personalized group tours to Copper Canyon and Batopilas twice a year.

Our adventure began in the Mexican border town of Ojinaga, Chihuahua, across the Rio Grande from Presidio. We boarded a bus in Ojinaga and three hours later arrived in Chihuahua City. From there we took a five and a half hour train ride to Creel, gateway to Copper Canyon, and our first introduction to the Tarahumara Indians who live in relative isolation throughout Copper Canyon. They come into Creel to sell their handmade crafts and textiles, brightening the streets in their colorful native attire.

The Tarahumaras, who prefer their indigenous name, Raramuri, have remained the most compact and unmixed of any of the Indian tribes in Mexico, deliberately choosing a life that is virtually untouched by modern civilization.The next morning, we piled into the van that would take us 6,000 feet down into the bottom of the canyon, and to Batopilas.

For this leg, we joined Ivan Fernandez, of The 3 Amigos and Copper Canyon Conexions. "He's a Mexican Indiana Jones," quipped Glendinning. Sure enough, Fernandez looked the part with a Panama hat, kerchief knotted at his throat and walking shorts. Slowly making our way downward, we drove past acres of logged pine forests that had caused extreme soil erosion. By lunch, we had passed the worst, and our driver pulled into a clearing with a view of the canyon below.

"Relax, enjoy yourselves," urged Fernandez, now dressed in a starched white chef's apron. He and Pedro Estrada, the driver, set up tables and chairs, and began to prepare an elaborate meal of steak and pork fajitas, guacamole and quesadillas made with local Mennonite cheese.

After lunch, the road began its plunge into the canyon which, together with the five other major canyons of the Copper Canyon region, is four times larger than the Grand Canyon. The pavement ended and the road narrowed into dizzying switchbacks, sometimes barely wide enough for a single vehicle.

The drive was both wonderful and terrible. The worse the road became, the more dramatic the scenery. My discomfort at wondering whether we would survive was matched by the thrill of the canyon. Its jagged bluffs and domelike shapes changed colors as the light faded from ochre, chocolate and rose to orange and purple. Because of our two-hour lunch and a couple of stops to walk along the road, a trip that usually takes four or five hours took us much longer.

"I want you to experience the canyon firsthand," insisted Fernandez, "not just from inside a vehicle."He was right. Outside the van, we were truly a part of the landscape, and besides, I felt much safer on foot.

Fernandez gave us a brief history of Batopilas. Silver was discovered in 1632 by the Spaniards, but it took Alexander Shepherd, a former politician from Washington, D.C., to bring it to full production in 1882, forming the Batopilas Mining Co. At their peak, Shepherd's mines were the wealthiest in the world, paying around $1 million in dividends per year. Eventually, the silver depleted, and in 1913 the mines were closed. Batopilas dwindled from a population of 8,000 to 1,200, once more lost to the rest of the world.

It was night when we arrived. After many twists and turns through narrow streets, Estrada pulled up in front of the Copper Canyon Riverside Lodge, white with blue and green trim and by far the most elegant hotel in town. Once the home of a wealthy merchant, this elaborate three-story Victorian mansion has been transformed into a fantasy hotel. The salons are decorated with ornate Victorian furniture upholstered in plush velvet, and the walls hung with paintings in heavy gilt frames. One of the room's lofty ceilings has murals depicting the town's history. The artist included the transport of a piano carried across the mountains by teams of Tarahumara Indians, in the 1800s.

With only 15 rooms, we had the place to ourselves, and it seemed more like our own private home than a hotel. On our first morning, I wandered to the dining room for a cup of dark, rich coffee. Gregorian chants and classical music echoed through the rooms. After a continental breakfast, we were ushered to Carolina's Restaurant for a "real" breakfast of huevos rancheros, eggs scrambled with cactus fruit, beans and fresh tortillas. Every morning and evening we dined at Carolina's. We were on our own for lunch.

Throughout the town, where there seem to be more burros than cars, stately buildings erected during the heydays of Batopilas Mining Company line the narrow cobblestone streets, grand, but somewhat faded leftovers of a time when the town prospered and enjoyed the latest improvements.

Since then, the tempo has changed. Television has not yet come to Batopilas; phones are a recent amenity. There are no taxis, but you can easily walk everywhere since the town is only 3 miles long, squeezed between the river and the mountains. There's no bank, so come prepared with dollars or pesos. All transactions are in cash.

Die-hard shoppers might be disappointed, but there are a few interesting places to spend your money. At the studio of a German artist, you can buy original paintings for several hundred dollars or a postcard of one for a few cents. Taller Guarache makes custom thong sandals, like the ones worn by the Tarahumaras. A high-end silver shop in one corner of the Riverside Lodge sells jewelry and handsome gift items, such as hand-woven Indian baskets and music CDs. You can also buy a "Batopilas" T-shirt in one of the little shops around town selling souvenirs and basic clothing.

Most of the restaurants are in private homes, with two or three tables out front. For a few pesos, ($1 equals about 10.80 pesos) you can have enchiladas, tacos and crisp chicken fajitas. Stop at the helado (ice cream) store just off the square for dessert.

Be sure to visit the Lost Cathedral of Satevo, built by Jesuits in the 18th century and known for its unique design and building materials. The road there winds along the river, passing gardens bursting with bougainvillea, hibiscus, poinsettias and mango trees.

The cathedral was built with bricks imported from Belgium rather than adobe bricks. Its dimensions are identical to those of the great cathedrals of Europe, although an abbot was never in residence here. Why it was built this way, or why it was built at all, in the middle of nowhere, remains a mystery.

On the edge of town, Shepherds Hacienda San Miguel, built at end of the 19th century, stands in ruins, overgrown by vines and purple bougainvillea. In the same complex are the remains of an assay office, reduction plant, refectory, stables and workers' quarters. It's worth a visit.

On our last night in Batopilas, Glendinning and Ivan prepared a surprise. After dinner, at the hotel we were greeted by a band of mariachis. As they played into the night, we drank tequila and sangria, danced and sang with the band.

Now a veteran, the trip back to Creel didn't seem quite as perilous, and it was certainly much shorter. After one last night at the lodge, we were on our way home. Across the border and back in Persidio where we picked up our cars, Batopilas seemed almost unreal, a memory of another world that ended long ago.

Fenstermaker is a Fort Davis freelance writer.

If you go ...

Avoid Easter to September, when it is much too hot. Glendinning's six-day Copper Canyon by Rail $990 per person; seven-day Copper Canyon (Batopilas) $1,290 per person. www.mexicosmallgroups.com.

Lodging for Sierra Lodge, Riverside Lodge, and throughout the canyon: www.coppercanyonlodges.com. Sierra Lodge $60 per person, includes three meals. Riverside Lodge $60 per person, no meals. Train through Copper Canyon www.nativetrails.com.

The 3 Amigos & Copper Canyon Conexions: truck rentals $120 for 24 hours. www.ccconexions.com. |

| |

|