|

|

|

Entertainment | August 2007 Entertainment | August 2007

Making Genocide in Darfur Personal

Ty Burr - The Boston Globe Ty Burr - The Boston Globe

go to original

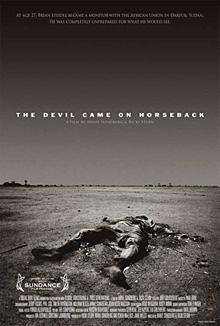

| | "The Devil Came on Horseback" by Annie Sundberg and Rickie Stern, which had its world première at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2007, impresses through its uncompromising portrayal of the Darfur conflict. |

"The Devil Came on Horseback" is a documentary about the human-rights crisis in Darfur. It's also about our response to the human-rights crisis in Darfur - not just the West as a whole, but you and me and the guy down the hall. You don't want to think about another faraway ethnic cleansing? Fine; here are pictures. You still don't want to think about it? All right - why?

If that sounds like a self-righteous guilt trip, the movie's anything but. Rather, filmmakers Annie Sundberg and Ricki Stern have built an engrossing, thought-provoking moral position paper on the back of one Brian Steidle, an ex-Marine who found himself working as a cease-fire monitor in Sudan in early 2004.

Steidle got the job via the Internet and quickly realized how deeply he was in over his head. The cease-fire between the Muslim government forces in the north of the country and the black animist revolutionaries in the south held everywhere but in the primarily Muslim western province of Darfur, where government-backed militias known as "janjaweed" - "the devil on a horse" - massacred entire villages, man, woman, and child.

Too often the movies view the problems of Africa through Western eyes, but "Devil" turns that weakness to a literal strength, because Steidle could do nothing in his position except take photographs. He returned to the United States after six months with hundreds of images of genocide: burned corpses, hacked children, body after body after body.

In time, this soft-spoken jarhead became radicalized, taking his photos to The New York Times and speaking out at rallies and colleges, pressing the Bush administration or the United Nations or anyone to do something to stop the ongoing carnage.

Steidle's photos are horrific beyond human imagination, and yet we still don't see enough of them. The film's first third, a limp collage-like re-creation of his journey to Darfur, doesn't hint at the sheer, damning mass of evidence he would come home with. It isn't until he begins his atrocity tour back in the United States that we understand what's at stake: a testament of genocide for a global citizenry that's afraid to even say the word.

Perhaps this is just novice filmmaking. "The Devil Came on Horseback" is on stronger ground when Steidle, accompanied by his sister Gretchen, returns to Sudanese refugee camps in Chad and speaks with men and women who've come away with only their lives, and barely that. One man tearfully thanks America for sending relief supplies, saying, "We receive nothing from the Arab world. We are Muslim, you know. They hate us, and they want us to hate others."

"Devil" wants very much to poke audiences in their hardened sensitivities, aware many of us are too busy shutting out the body count in Iraq to think about a preventable human-rights catastrophe in northern Africa. The film shows chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo of the International Criminal Court in The Hague readying a case against the Sudanese government that has yet to bear real fruit. Steidle is seen visiting genocide memorials in Rwanda and crumbling in exhausted tears over how little we've learned.

The film's tight focus on the West's complicity-through-inertia means that larger political complexities get lost: The part Russia and China are playing in arming the janjaweed, for instance. What is in the film, though, renders it both deeply frustrating and necessary viewing. Hundreds of thousands are dead and millions have lost their homes. A 26,000-man UN peacekeeping force is due to arrive in Sudan by December, but attacks have recently flared up anew. "We've said 'Never again' again and again and again," says a weary Steidle at a rally on the National Mall. "And here we are again." |

| |

|