|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | September 2007 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | September 2007

Frida Kahlo Lives On in Mexico

Paul Pihichyn - TheRecord.com Paul Pihichyn - TheRecord.com

go to original

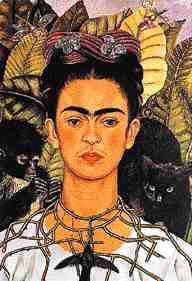

| | This is a self-portrait of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. (Canadian Press) |

Mexico City - If the allure of the world's most populated urban area isn't enough, then the cobalt-blue house at the corner of Calles Allende and Londres may be all the reason you need to visit Mexico City.

Casa Azul - literally, Blue House - was the home of Mexico's surrealist art icon, Frida Kahlo. It was where she was born in 1907, where she grew up and where she lived while married (twice) to Mexico's other national artistic treasure, Diego Rivera.

It was where she convalesced after a life-altering accident - in 1925 she was riding a bus in Mexico City that collided with a streetcar. She suffered dozens of broken bones. Her abdomen was impaled by an iron rod and her uterus was pierced.

It was during her long recovery that she turned to art. Bed-ridden, she painted self-portraits drawn from images in a mirror mounted above her broken body.

Her art caught the attention of Rivera, the most famous Mexican artist of his day. They married - for the first time - in 1929. After a brief divorce, they remarried in 1940.

The Tate Modern Gallery in London calls Kahlo "one of the most significant artists of the 20th century." Her tragic life and haunting art came to the big screen with the 2002 movie Frida. Kahlo was portrayed by countrywoman Salma Hayek.

A socialist and communist sympathizer (she had a brief love affair with Leon Trotsky, her neighbour in Mexico City's Coyoacan district, where Casa Azul is located), Kahlo has long been revered by the political left and is a beacon for the gay community because of her open bisexuality at a time when such things were normally kept locked deep in one's closet.

Now, in the centennial year of her birth, Casa Azul has become a magnet for visitors to Mexico City. It is a museum and gallery, and more important, a tribute to her life. After her death in 1954, Rivera turned the property over to the Mexican people.

Behind those walls at 247 Calle Londres, the colonial-era house is shaped like a U that opens onto a tree-lined central courtyard - a cooling oasis under what can be a broiling summer sun.

Tropical plants line the walkways that lead to a gallery, gift shop and tea room. One can imagine Kahlo playing here as a child after a bout of polio cut her off from the rest of the world. But it is inside Casa Azul that visitors truly come into contact with Kahlo and her tortured life. A guide leads tours from room to room, or visitors are free to wander the house on their own. The walls are lined with her paintings, her personal effects - clothes, jewelry, even her hand-written diary. There are also works by Rivera. The dining room, the kitchen and bedrooms have all been meticulously restored and preserved.

Our guide points out the master bedroom, conveniently adjacent to the dining room - convenient, that is, for the 300-pound Rivera. Beside the frail and diminutive Kahlo, the couple was quietly referred to as The Elephant and The Dove.

The paintings are striking. Perhaps none more so than Viva la Vida (Long Live Life), a brilliant still life of watermelons, the seeds depicted as sperm. Kahlo's inability to have a child after the accident is a recurring theme in her work.

After touring what is more a shrine than a house, visitors can watch a 30-minute video of Kahlo's life in an outdoor theatre under swaying palms. Casa Azul is open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., closed Monday. Admission is 45 pesos ($4.50 Cdn); 20 pesos ($2) for students and children.

This neighbourhood, 12 kilometres southwest of the zocalo at the heart of Mexico City, is a treasure trove of history, art and culture.

The Trotsky house, where Leon and Frida are said to have met for afternoon encounters, is a 10-minute stroll from Casa Azul, at 45 Viena, at the corner of Calle Morelos.

It was here on a warm August night in 1940 that a man calling himself Jacson Mornard and carrying a false Canadian passport talked his way in and smashed an ice pick into Trotsky's skull. Trotsky died the next day in hospital.

The assassin known as Mornard was, in fact, a Stalinist agent dispatched from Moscow by Joseph Stalin himself to silence the Ukrainian-born Trotsky, who had been expelled from Russia in 1929 for his criticism of the brutal dictator.

The house is now a museum. Trotsky's ashes are buried here. Visitors are guided through the rooms by members of the Trotskyite Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores (Workers' Revolutionary Party).

Trotsky's study is just as it was on the day he was dealt the fatal blow, with his broken spectacles still lying on the desk. The walls of the simply furnished bedroom show bullet holes from an earlier attack by Stalinists in which the famed Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros was involved. The museum is open every day except Mondays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is 20 pesos ($2).

Just about anywhere a visitor ventures in Coyoacan, vestiges of the Bohemian lifestyle of the era of Kahlo, Rivera and Trotsky remain. But Coyoacan - the name means "place where they have coyotes" - has a much older history.

Before the Spanish conquest in 1521, Coyoacan was a town of its own and a major centre of trade on the southern shore of Lake Texcoco. (The lake was subsequently drained by the Spanish, but that is another story.)

It was a hallowed ground to the Aztecs and the site of a major temple - actually the second most important temple in the empire. After the conquest, Hernando Cortes, the Spanish governor, made his residence here.

A few years later, Franciscan friars built a monastery on the site, using the stones of the Aztec temple. Nearly five centuries on, it remains. Coyoacan continued as a separate town until 1950, when it was swallowed up by the sprawl of Mexico City.

Coyoacan is just one small part - one of 16 boroughs - of a city with a population of 22 million or 25 million or 30 million. No one knows for sure what Mexico City's population really is. As many as 600 people move to the city every day, migrating in search of a better life, escaping the poverty of the countryside, joining the working class, struggling to survive.

Frida Kahlo would be proud of them. |

| |

|