|

|

|

Vallarta Living | Art Talk | October 2007 Vallarta Living | Art Talk | October 2007

Tony Gleaton Aims Lens at Black Mexicans

Sean Mitchell - LATimes Sean Mitchell - LATimes

go to original

| | Tony Gleaton shows his photographs of present-day descendants of African slaves brought to Mexico in the 1500s by Spanish colonists. The exhibition "Africa's Legacy in Mexico: The Photographs of Tony Gleaton" is at the Burns Fine Arts Center at Loyola Marymount University through Nov. 18. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times |

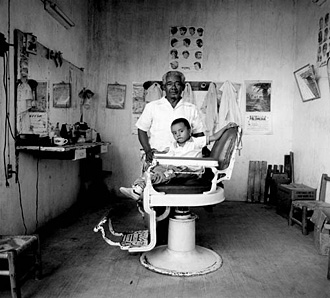

| Tony Gleaton's gelatin silver print of "Peluguería" (Barber Shop), 1990, was shot in the town of Pinotepa Nacional, Oaxaca, Mexico. (Tony Gleaton/Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University)

Click HERE for Tony Gleaton's photo gallery |

Race is not an issue for Tony Gleaton, the photographer told students at Loyola Marymount University recently. Yet an irresistible musing on the meaning of race has been his destiny. Born with blue eyes and a fair complexion, Gleaton, 59, has spent his life explaining to people that both of his parents were black and that he is "not biracial," while wondering why anyone should care. It's not surprising, perhaps, that Gleaton has made his reputation with a series of portraits of black Mexicans, descendants of slaves brought to Mexico by the Spanish conquistadors 500 years ago, "before the first black slaves came to Colonial Williamsburg," he pointed out.

He began taking the photographs in the 1980s, and exhibitions, sponsored in part by the Smithsonian, have carried them across Southern California, the nation and the world for the last 15 years and now back to Los Angeles, where "Africa's Legacy in Mexico" is on exhibit at LMU's Laband Art Gallery through Nov. 18.

The relevance of Gleaton's fine-art photographs of these people from villages on the Pacific Coast has not diminished as immigration and multiculturalism continue to challenge traditional views of what it means to be an American. The exhibition, in fact, is part of a larger colloquium on migration and immigration taking place this fall at the university.

Before his informal lecture in the gallery, Gleaton spoke about his work in an interview and wanted to make clear that he does not take credit for discovering that descendants of African slaves were living in Mexico. "What I did was provide the first visual depiction of something scholars had written about," he said.

A native of Detroit who moved with his parents to Los Angeles when he was 19 and attended UCLA and the Art Center College of Design, Gleaton learned his trade working in fashion photography in New York City but at the age of 35 made a course correction. In the world of fashion photography, he said, he came to feel that he was "propping up an aesthetic that was not in my best interests, photographing 15-year-old ingénues."

He left New York and set out to apply his skills to more thematic subject matter, hitchhiking through the West while photographing cowboys, Native American ranch hands and black rodeo riders, "reconstructing an American myth," part of the title of that collection.

Following the rodeo south to Mexico, he heard from an acquaintance about some isolated villages on the coastal plain south of Acapulco where the inhabitants were black. He doubted the truth of this until he journeyed there and saw for himself. Drawn to the notion of an unexamined African diaspora, he proceeded to document the evidence his own way, living among his subjects for months at a time and posing them for photographs intended to magnify their humanity and beauty. "This is not journalism," he said. "I am making art. I'm trying to craft a photo. I don't record moments. I make a statement."

In the gallery, surrounded by the 44 framed and mounted photographs that make up the exhibition, he told the students that they should view the painterly black-and-white portraits of these common folks as reflections of the photographer as much as his subjects. "These photos are about me," Gleaton said, somewhat provocatively. "It's an image of where I might be coming from at a particular time. These are lies telling a larger truth."

Where Gleaton was coming from was, if not strictly reportorial, then sociological and aesthetic. "What's important about these photographs is that they gave a face to something that nobody had really thought about before. And it's a place to begin the discussion about what we suppose Mexico to be. We have a stereotypical view of what Mexico is, and Mexico is many things. You can have freckles and red hair and be Mexican - and you can have very black skin and be Mexican."

Invoking the prejudice that "You can't be too thin, too rich or too white" as a residual "post-colonial mindset" in Mexico, as well as the U.S., Gleaton said he chose not to classify his subjects as Afro-Mexican, "because that's more the way we see things. I don't believe in race. It's a social construct, not a bio-empirical fact."

Asked what, if anything, his experience in high-fashion photography contributed to these glossy, vibrant portraits of fishermen, farmers, teenage couples and children, Gleaton stretched out his long arms, pointing to the walls in both directions. "Everything," he said. "These are beautiful photographs of people who are not normally portrayed in beautiful ways."

The element of subversion in his method is no accident, he explained. "My whole thing is doing projects that take a supposed thing and turn it on its side." Gleaton is a large man, 6 foot 3 and about 360 pounds, and on this day at Loyola Marymount, dressed in shorts, with an untucked dress shirt and long-billed cap, he proved himself to be a figure of contrasts, by turns imperious and self-deprecating - glib and casual one moment followed by almost formal enunciations on his theme of provoking thought and understanding with his art.

He told the students that a camera was only a tool and that he did not use expensive equipment. The photographs on display, he said, were taken with a Mamiya (Japanese) twin-lens reflex camera using only natural light and shooting 2 1/4 -inch square negatives that were painstakingly developed to achieve their subtle tones. "Black skin in shadows," he said, underscoring the degree of difficulty involved in producing results of such resonance and clarity.

"They may look natural but they are extremely crafted," he said. "Very calculated. They are abstractions from daily life."

Although in a few of the portraits in "Africa's Legacy in Mexico" the person is looking away from the camera, most of them are notable for their dead-on eye contact and luminous stares.

"They draw you in," said Carolyn Peter, the director of the Laband gallery. "You want to sit down and have conversations with these people about their lives. And you feel the collaboration between the subject and the photographer."

As he took the photos, he thought about the question, "What is black?" And Gleaton couldn't help but think that he was taking pictures of people who would not know the answer to that question or who might not approve of his asking it.

He also expressed ambivalence about earning money from the photographs, even though he spent years strapped for funds, "bumming around Mexico and feeling like a fool" while pursuing the project. He said some of the photos had been sold for high sums to Hollywood celebrities but that he stopped doing that: "I became uncomfortable with the thought of wealthy people owning pictures of not-so-wealthy people."

Gleaton eventually extended the project to include countries in Central and South America, where the African diaspora is also present. But this is all old news to him now.

Now he's working on a landscape project called "The Black Route West," tracking exploration and settlement of the West by former slaves and other blacks. "A lot of what we believe now is based on the myth of the past," he said. "And there are a lot of interesting things that most people don't know." |

| |

|