|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | October 2007 Entertainment | Books | October 2007

Bush Was 'So Deeply, Deeply Wrong,' Says Fox

Excerpts from new book 'Revolution of Hope,' by Vicente Fox and Rob Allyn Excerpts from new book 'Revolution of Hope,' by Vicente Fox and Rob Allyn

go to original

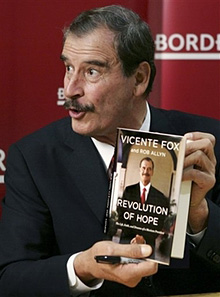

| | Former Mexican President Vicente Fox holds up a copy of his new memoir 'Revolution of Hope' while speaking to customers at a book signing in Washington last week. (AP/J. Scott Applewhite) |

I am absolutely certain that George W. Bush did what he believed he had to do in Iraq in order to protect his country and the world from evil. Surely those who accuse him of playing politics must be wrong, since the politics of his wartime presidency have turned out rather badly. ... On Iraq, I think that George W. Bush did what he deeply believed was right. The sad thing is that he was so deeply, deeply wrong.

There is a more profound principle at stake here: the future of global democracy. After the United States admitted that its intelligence had been incorrect, that there were no weapons of mass destruction, the war party changed its rationale for the occupation of Iraq as a battle for democracy. But where was this passion for global democracy when the United States went to the United Nations for the vote to authorize the use of force? When the United States and United Kingdom couldn't get the majority of votes from the institution of world peace ... the United States simply withdrew from the process of global democracy and invaded Iraq anyway.

So when people ask me, "Why does the world hate America?" I answer that we don't hate America. But at times we do wonder whether America hates the world – or at least does not respect us. In a true global democracy, our vote should count, too, when decisions are made that affect the planet.

Immigration

Texas lawmakers passed a bill giving in-state tuition to the children of undocumented workers. Utah gave them driver's licenses. American banks began accepting the matrícula, the consular ID card issued by the Mexican government to our citizens abroad. While the undocumented immigrant cannot prove that he is a citizen or legal resident of the United States, the matrícula is vital, because it at least enables immigrants to prove that they are who they say they are. This card certifies that an immigrant is a law-abiding, job-holding, taxpaying worker with a name and this spouse or that child, capable of renting an apartment, opening a bank account, driving a car, getting insurance, repaying a loan, even buying a home. The Mexican haters in the United States despise the matrícula, considering it a backdoor trick of our government to help "illegal aliens" beat the law. In fact, it is the opposite: The consular ID merely provides the immigrant with the means of declaring that he or she exists as a human being, ready to comply with the laws and rules of the United States and Canada. ...

The saddest legacy of this bracero program [a 1942-64 guest-worker program criticized as exploitative] is the terrible precedent it set for the new, more enlightened program of temporary employment that George W. Bush and I would pursue in our presidencies, based on the modern European model, where an immigrant's human rights are respected and social needs met. South of the border, we encountered great skepticism from a society that still remembers the tragedy of the braceros. North of the border, Mexicans are seen only as migrant crop pickers who have too many babies in the hospitals of California and Texas, expecting border-state taxpayers to pick up the tab. It is this bleak pattern of mutual misunderstanding that dominates the debate on immigration. On one side of the Rio Grande, the poorer nation, fearful of domination and exploitation; on the other side the wealthy country, fearful of losing its economic advantages, personal security and cultural integrity to a flood of unskilled farmhands who live six to a room and work cheap. Immigration, say the xenophobes to the south, will destroy our Mexican way of life. "Immigration," say the xenophobes to the north, "will destroy our American way of life."

Most embarrassing moment

Sometimes the tendency to speak on the run or act out of turn is not such a good quality. In May 2005, my own propensity for verbal gaffes brought me into contact with the Reverends Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. As my presidency moved into its maturity, immigration reform in the United States faced the constant banging of the anti-Mexico drum by right-wing talk shows. There also was criticism from the American left against immigration and free trade, especially from labor-union protectionists from Rust Belt states who blamed Mexicans for "taking our jobs away." Some African-Americans even complained that immigrants and Latinos were "cashing in" on the hard-won progress they had fought for in the civil-rights movement.

Speaking in Spanish from Mexico City, I said that the United States needed our workers because "there is no doubt that Mexicans, filled with dignity, willingness, and ability to work, are doing jobs that not even blacks want to do there in the United States." Bad wording. Bad day at Los Pinos [the presidential palace].

First, it was a borderline racist thing to say. Implicit in the way I misspoke was the idea that African-Americans were willing to take some jobs that Anglos didn't want, but not those jobs that were going to immigrants, or, worse, that Mexicans were harder-working than African-Americans. It was the wrong thing to say, and I never meant it to come out that way. ...

It pained me, as have few other things in public life, to read in the international press that the Reverend Jesse Jackson had called me a racist. The Reverend Al Sharpton phoned me to demand that I apologize. So I did. ...

I hoped for a rapprochement with African-American civil-rights leaders, because Mexicans must engage more closely with those who have suffered discrimination. We have common cause on the moral high ground of human rights and social justice for the dispossessed. When we argue over who has it worst, we all lose.

From Revolution of Hope, by Vicente Fox and Rob Allyn. |

| |

|