|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | October 2007 Entertainment | Books | October 2007

Katz’s “The Face of Pancho Villa”

BYLINE BYLINE

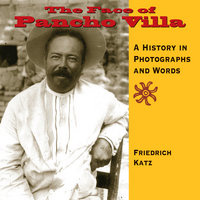

| The Face of Pancho Villa: A History in Photographs and Words

By Friedrich Katz

Cinco Puntos Press

83 pages, $12.95 |

The Face of Pancho Villa is the latest title in the Cinco Puntos Press Mexican Revolution Collection, and it’s aptly named: Villa’s immediately recognizable face stares out of from almost every photo in the book, with his heavy moustache, round cheeks and chin, and mischievous dark eyes. Ever since the teenaged Villa shot a man who may have raped his 12-year-old sister, stole a horse and fled into the Sierra Madres before returning to civilization and eventually joining the revolution, he has been an iconic figure in the Southwest, both among those who consider him nothing more than a bandit and those who count him as a hero to the poor.

Scholar Friedrich Katz lays out the basic chronology of Villa’s life from the historic record, including some popular verses that were written about him, eyewitness accounts, and newspaper articles. And though Katz digs up some gems, the reader’s eye is sure to wander over to the photos, which show Villa in his prime, mounted on horseback, wearing a sombrero, interacting with children and important figures in the revolution. There are photos of Villa with Emiliano Zapata, whose followers still fight in Mexico today, and several of Villa’s many lady loves, and shockingly, a photo of Villa taken just after he was assassinated, having fallen backwards over the side of his car, his arms dangling down toward the street while passersby look on gravely.

An afterward explains the source of this wealth of photographs, which were selected from the archives of the Casasola Collection in Mexico’s Fototeca National. The afterward cites David Romo‘s assertion that the Mexican Revolution was the first war to “allow all access passes to photojournalists” (not the Spanish Civil War, as Susan Sontag claimed in On Photography). The Casasola brothers formed “one of the very first photographic agencies to take advantage of interest in the Mexican Revolution.” And though Agustín Casasola was notorious for purchasing other photographer’s prints, scratching off their names and adding his own, he can be thanked for preserving the archive.

Reflecting on Villa’s early life after he had been forced to serve in the army and subsequently deserted and changed his name to Francisco Villa, Katz writes, “In Chihuahua, he led a life of contradictions. One the one hand, he made an honest living as a muleteer and as an employee of foreign corporations. They recognized his talents as a leader of men and frequently employed him to transport goods or even money that he seems never to have stolen. On the other hand, he was also a cattle rustler.”

The contradictions continued throughout Villa’s life. Katz writes, “He didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink--when he occupied a city all saloons were closed--but his love of women was all embracing. He married at least four women without divorcing his previous wives.” It’s impossible to verify how many girlfriends he had or children he fathered.

In matters of love and war, Villa seems to have often relied on his charisma. Katz quotes a great description of Villa written by an American acquaintance when Villa was 35: “He has the most remarkable pair of prominent brown eyes I have ever seen. They seem to look through you, he talks with them and all of his expressions are heralded and dominated by them first…He is a remarkable horseman, sits on his horse with cowboy ease and grace, rides straight and stiff-legged Mexican style.” Most who met Villa seemed to have fallen under his spell, at least for a while, including U.S. leaders who supplied him with arms until Woodrow Wilson became President and threw his support behind Venustiano Carranza.

Villa is still revered by many today, even though he executed enemies by firing squad, robbed trains, and even attacked the United States, leading his army into Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. Katz writes that he could be “extremely cruel. In a fit of anger he was capable of killing, often regretting his actions later.”

So why is Pancho Villa still admired by some? According to Katz, he became known as “a friend of the poor” in part because he seized haciendas and divided the land among poor campesinos. But I wonder how much of Villa’s continuing notoriety can be accounted for by his well-known image. Although his image hasn’t become a dorm room poster and t-shirt cliché like that of Che Guevara, the photographs in The Face of Pancho Villa evidence that Villa, who has been dead for over eighty years, still conveys his charisma to anyone who looks at his image. |

| |

|