|

|

|

Travel & Outdoors | November 2007 Travel & Outdoors | November 2007

Choosing to Swim With the Sharks

Pete Thomas - Los Angeles Times Pete Thomas - Los Angeles Times

go to original

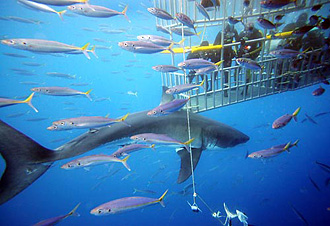

| | Divers in cages watch a great white shark off the shore of Guadalupe Island, a 22-mile-long volcanic land mass 150 miles west of Baja California. The island has emerged in the last five years as perhaps the worlds premier destination for diving with especially large great white sharks. (Al Seib/Los Angeles Times) |

Caged divers face fears and get close, personal look at predators at Guadalupe Island off Baja coast. The experience is exhilarating, even as rumors swirl over methods used to draw out the beasts.

Guadalupe Island, Mexico - The mammoth predator is lured from the abyss by the scent of blood, and looms larger with every fathom it covers.

My heart races as I turn this way and that, sucking air through a hose, peering through a mask, intently following its progress.

Upward the shark swims, slowly, warily, casting a vacant gaze through ominous black eyes. Dagger-like teeth protrude from its lower jaw.

Forty feet . . . 30 . . .

This colossal specimen, 16 feet long and 2,000 pounds, could sever a man with little effort.

Yet its movements are surprisingly cautious. It's as if thousands of years of evolution have taught it to leave nothing to chance, to give thorough inspection.

I'm behind the bars of a submerged steel cage, but it has gaps wide enough to swim through and I keep leaning out to gain an unobstructed view, then jerking back because of fear and paranoia.

Twenty feet . . . 10 . . .

Anxiety builds until, for some reason, it becomes exhilaration. I'm overwhelmed with desire to film this remarkable creature.

So again I reach out and hold my camera steady, as the shark glides closer and closer still, until its menacing face fills my monitor and I glance up to discover that this great predator is only a few feet away.

Our eyes meet and I pitch back inside, startled to my senses, stumbling under the heft of my weighted harness. Cindy Rhodes, my cage partner, has also fallen back. We glance bug-eyed at each other while trying to regain our composure.

Back aboard the ship we'll learn that ours is a common reflex - although divers are told to keep all limbs inside - and that our clumsy waltz even has a catchy title: the "White Shark Shuffle."

It's performed frequently each summer and fall in the strikingly blue water flanking the eastern shore of Guadalupe Island, a 22-mile-long volcanic land mass about 150 miles west of Baja California.

Guadalupe emerged in the last five years as perhaps the world's premier destination for diving with especially large great white sharks, and with such distinction has come controversy and concern.

Competition is fierce among the five commercial outfitters permitted to dive here. Regulations are strict but almost impossible to enforce because the Mexican park service cannot afford to police so far-flung a destination.

Thus, outfitters are wary of one another and rumors swirl regarding this boat or that, about questionable chumming tactics - and risking of lives.

"If you don't play by the rules, you make life difficult for the park service and place all of this in jeopardy," says Mike Lever, captain of the Canada-flagged Nautilus Explorer, who will not point fingers. "We need to stand together in order to make this industry sustainable."

Outfitters charge up to $3,000 per person for a five-day excursion, which includes three days of diving.

White shark seekers, whose only viable options are South Africa or Australia, consider a Guadalupe voyage extreme adventure, a chance to face fears and bond with others while becoming intimate with the ocean's most notorious, yet misunderstood, predator.

"Your photograph doesn't show the size. It doesn't show the gracefulness," says Cathy Church, a photography instructor from Grand Cayman. "Even video doesn't show what it's like to share the same water as this animal goes by."

"And he only gives you a fleeting moment. He doesn't warn you by saying, 'Oh, I'm coming. Get ready.' He just comes into view and goes out of view at his own whim."

Journey, anticipation

We're aboard the Nautilus Explorer, a 116-foot gleaming white vessel with four large cages secured to the stern deck.

Ensenada, our point of departure, is a distant memory. We've slept the night, dreamed of sea monsters, and awakened to find we're still at sea, with no land in sight.

It takes 20 hours to reach Guadalupe Island. We ponder its remoteness, check our gear and get to know one another.

Many aboard are Brooks Institute of Photography alumni, who studied under and now accompany Ernie Brooks, the founder's son.

Also here is Zale Parry, who starred in the late 1950s TV show "Sea Hunt." Parry and Brooks are in their 70s. The youngest are 30-somethings Kelly Kirlin, Sara Shoemaker Lind, Mark Meyer, Mark McWilliams and Scott Henderson.

Many have left worried family members behind, and no one feels the emotional tug like Henderson, a bail bondsman from Costa Mesa who has just discovered, buried in his luggage, a colorful booklet containing photos of his wife and two young daughters.

On the last page, in white lettering on blue paper, are the words: "We love you daddy. Don't get eaten by a shark."

At last, the island's faint outline comes into view. Two hours later, as darkness falls, we're alongside its towering shoreline, bombarded by tiny seabirds not accustomed to bright lights.

The dive masters are already at work. "Scuba Joe" Gonzales and Graham "Buzz" Busby are drilling holes in frozen tuna, then sawing them into chunks. Sten "the Viking" Johansson, a towering, long-haired Swede, has affixed to the stern oozing sacks of chum, which lures thousands of footlong fish.

Looming over the water like a grizzly over a salmon stream, Johansson swipes with his paw and launches a mackerel onto the deck.

Laughter wafts into the blustery night. An elephant seal barks. A million stars flicker. Somewhere beneath us, in the inky depths, very large creatures stir. Sleep comes uneasily for some.

Total immersion

Dawn is gray and breezy. Two cages are secured to the stern, their floated tops at water level. Two more have been pushed 15 feet from either side of the vessel via outrigger booms.

Richard Salas, Shoemaker Lind, Henderson and Meyer have already slipped into stern cages. Air is supplied hookah-style, via hoses. Scuba certification is not required.

There is only one other vessel here: the Solmar V, 400 yards to our north. Both are dwarfed by barren island cliffs and hillsides.

The Solmar V is also a luxury live-aboard. But its operation is unique in that its cages can be submersed to 30-plus feet, offering more close encounters, says expedition leader Lawrence Groth.

Some consider Groth a cowboy. His submersible cages are open-topped and divers can sit atop their rails as they're let down or brought up.

He also has a "cinema cage" with no sides, affording unobstructed views through side gaps eight feet tall and four feet wide. The gaps are big enough for any of the sharks to swim through and attack divers inside, but Groth said the sharks don't act aggressively toward divers and said he has never had an incident with that cage.

Groth denies that he has let passengers swim freely with the sharks, as one person has alleged in a blog. But he once did so with a knife, to cut a large plastic box strap that had become wrapped around a shark's head and gills.

"It was a bit of a cowboy move, but he probably saved the life of that shark," says Michael Domeier, a researcher who witnessed the incident.

There have been no attacks by sharks on humans since the cage-diving operations became full-scale in 2002. But sharks have stuck their noses and in some cases their heads into the gaps between bars, and during at least a few of these so-called breaches, the predators have had to twist wildly to free themselves. In at least one case, involving one of Groth's trips on the Searcher this month, part of the cage broke apart, briefly exposing the divers.

As part of an evolving code of conduct, each vessel is allowed to use only five tuna per day. Processed chum can no longer include cows' blood; it must be fish-based. Hand-dragging roped tuna to lure sharks to or between cages, formerly practiced by some, is no longer allowed.

Lever says he plays by the rules. Groth adds, "There's no bad things going on here."

'Shark!'

Finally, there's a sighting and the topside cry. Divers scramble into wetsuits. I'm directed to the port outrigger cage and await my first encounter.

There's a fleeting glimpse, then another, of a wide-bodied shark that is reluctant to surface. But even 20 feet down it looks monstrous or, as Shoemaker Lind describes, "cartoon-like."

Lever explains that sharks don't like surface chop and adds that the wind will subside overnight, so passengers acclimate and learn about the 100-plus adult white sharks that begin to arrive in July and stay into December.

Studies reveal they make a winter pilgrimage to a featureless mid-Pacific destination known as the "White Shark Cafe." Sharks from the Farallon Islands off San Francisco also migrate there, yet it's unknown whether Guadalupe sharks have visited the Farallones, or vice versa.

Also a mystery at Guadalupe is what their primary food source is. Farallon sharks prey almost exclusively on elephant seals. At Guadalupe in recent years, white sharks have commonly devoured large yellowfin tuna hooked by anglers. Though there are three types of pinnipeds here, eyewitness accounts of attacks on them have been sparse.

However, Mauricio Hoyos, a researcher from La Paz, has joined us from his island outpost - only seasonal fishermen and scientists live on the island - and reports that "just yesterday" a large shark ambushed an elephant seal, severing its head. It then consumed the mammal while aggressively fending off other sharks.

Our second morning is calmer, the sharks much bolder, rising sporadically to inspect or chomp on large chunks of tuna cast off the corners. This is when divers learn how apprehensive the sharks are. Tuna tied to tear-away hemp ropes is unnatural, so minutes, sometimes hours will pass before the tuna is consumed.

"I was a little nervous at first and kept referring back to Nemo and that one big shark," says Mark McWilliams, a photographer from Dallas. "All these things play back in your mind - all the movies you've seen and stories you've heard - and then when you finally get to see it for yourself you realize, 'OK, they're all right.' "

Jim Holm, a doctor from Utah, emerges from the port outrigger cage with video footage of a shark that became entangled briefly in the rope, then shook from side to side and opened its massive jaws one foot from the cage.

It becomes the highlight of the nightly video-rewind in the salon, though I'm honored simply to have footage of my late afternoon close-up even shown before such an illustrious group.

I didn't know that I'd spent three straight hours in that cage, waiting for a shark named Squire to mug for my camera. But time does zip by when you're watching predators the size of SUVs materialize beneath the boat, over your shoulder or behind your back, then disappear like phantoms in this bluest of realms.

Too quickly it's the afternoon of our third and final day, and what an encore performance . . . several large sharks are alternating appearances behind the stern, passing close enough to touch.

One veers away, then another arrives. At one point, two cross paths and turn to swim side by side, as if to size each other up, before the larger shark is given unchallenged access to the baited lines.

The spectacle seems as impressive from the top deck, but as the wide-eyed divers begin to emerge it's clear that what they'd witnessed, for hours on end, was something truly extraordinary.

"I can't believe it really happened," says a shivering Kirlin, who as a specialist in creating underwater portraits will go home armed with proof that, yes, all of this really did happen.

pete.thomas@latimes.com |

| |

|