Rivera, Fridamania’s Other Half, Gets His Due

Elisabeth Malkin - NYTimes Elisabeth Malkin - NYTimes

go to original

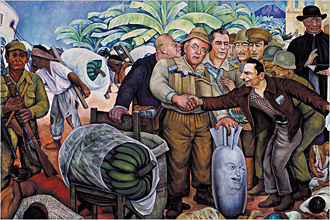

| | A detail from "Gloriosa Victoria." Rivera is best known for his Mexican murals, particularly in the National Palace and the Ministry of Education. If these seem rather earnest today, it is worth remembering, as Juan Coronel Rivera, an art historian and a grandson of Rivera, points out in one exhibition catalog, that Rivera and the Mexican muralists created the first major Modern art movement on the American continent. |

A Communist who painted murals for the great capitalists of his day, he offered an epic view of history and a cosmic vision of human potential.

Mexico City — It’s easy to forget that at the height of Diego Rivera’s fame, in the 1920s and ’30s, he had star power. A Communist who painted murals for the great capitalists of his day, he offered an epic view of history and a cosmic vision of human potential. But in the last few decades here, his reputation has been vastly eclipsed by Fridamania, the cult status of his third wife, Frida Kahlo.

“It’s ironic that this artist who painted miles and miles of frescoes is not as well known as his wife, who painted almost miniatures,” said Linda Downs, an expert on Rivera’s American murals.

Yet on the 50th anniversary of his death, this city is in the midst of a series of exhibitions celebrating his work, a tribute that shows his wide range, including not just frescoes, but also paintings, watercolors, sketches and even magazine covers. (The Kahlo worship, though, continues unabated: A retrospective this summer at the museum of the Palacio de Bellas Artes here drew about double the number of visitors as the recent Rivera show there.)

Rivera is best known, of course, for his Mexican murals, particularly in the National Palace and the Ministry of Education. If these seem rather earnest today, it is worth remembering, as Juan Coronel Rivera, an art historian and a grandson of Rivera, points out in one exhibition catalog, that Rivera and the Mexican muralists created the first major Modern art movement on the American continent.

But Rivera’s reputation later sagged because simplistic interpretations of his work failed to understand the reach of his curiosity and philosophical interests, Mr. Coronel said.

“Diego was looking for knowledge first, the great knowledge of the human being, the notions of space and time,” he said. “What hurts Diego the most is first, the vision that’s imposed on him from the United States as a Communist, and second, Mexico’s own centralist vision that made him a historical painter.”

The sheer volume of work on display in the commemoration rescues Rivera from easy classification. The national homage, as it is billed, involves five exhibitions in Mexico City (including the Bellas Artes show, which ended last week) and one in Rivera’s birthplace, Guanajuato.

“Diego was a deluge of work,” said Raquel Tibol, a prominent art critic and historian who organized one of the shows. “He was too dynamic, and so many cultural themes opened his interest in a very vibrant way.”

There are the huge works: Rivera produced part of a giant mosaic to adorn the city’s Olympic Stadium, murals for hospitals, government buildings and even hotel bars. The Bellas Artes exhibition showed portable murals from private collections as well as sketches and cartoons of the larger murals.

At the National Museum of Art, the first comprehensive show of Rivera’s illustrations reveals an unexpected diversity in style and subject matter over 50 years.

He produced simple line drawings for primers published by the education ministry in Mexico’s post-revolutionary government of the 1920s. He illustrated Yiddish poems by an immigrant Jewish poet, Isaac Berliner, in a vivid Expressionist style; drew for André Breton’s Surrealist review Minotaure; and put the hammer and sickle on a Fortune magazine cover commissioned in 1932.

He also used pre-Hispanic motifs in drawing covers for the magazine Mexican Folkways, and created illustrations for the Mayan sacred book, the Popol Vuh, that drew elements from Mayan inscriptions.

“Rivera didn’t conserve his own style,” said Ms. Tibol, who oversaw the exhibition. “He put it at the service of the text.”

At the Dolores Olmedo Museum in southern Mexico City, a collection of some 50 portraits begins with a pencil drawing of Rivera’s mother that he did when he was 10. Rivera painted Mexican movie stars and members of high society, but it is his simple portraits of Indian peasant women that are the strongest. A painting of his second wife, Guadalupe Marín, stands out for its vitality.

Ms. Downs, the author of several books on Rivera’s American murals, contends that there is a renewed interest in studying the politically charged realism of the 1920s and ’30s.

“It’s being re-evaluated as a legitimate aesthetic movement, where before it was written off, especially by those critics who were promoting Abstract Expressionism and Modernism.”

Rivera’s emblematic looks at Mexico’s distant Indian past and its recent (for him) revolutionary history endure as defining images both inside and outside the country. But for an artist so linked in the popular imagination with Mexico, the exhibitions are also a reminder of his ties to Europe and the United States. He lived overseas, mostly in Paris, from 1907 to 1921, where he experimented with Cubism.

It was only after he returned to Mexico at the end of a bloody decade of fighting that he began to create the work that made him famous. As he turned frescoes on public buildings to universal themes, he melded elements from European masters and Modernists with pre-Hispanic forms and designs to create his own pictorial language.

But by 1929, as revolutionary fervor veered toward authoritarianism, and Rivera fell out with the Mexican Communist Party, he accepted an offer to paint in San Francisco. He spent four years in the United States.

After California, Rivera and Kahlo went to Detroit. There his patron Edsel B. Ford opened the doors of the largest Ford plant, and Rivera carried out the research for his landmark mural cycle at the Detroit Institute of Arts, a series celebrating the auto industry and the capitalist worker at its heart.

New York followed, where Rivera was to paint a mural in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. But after he rejected a request by Nelson Rockefeller to remove a portrait of Lenin, the mural was covered and then destroyed. He later repainted it in Bellas Artes, calling it “Man, Controller of the Universe.”

After that debacle, he created a series of portable murals, “Portrait of America,” for the New Workers School in New York. Several were in the Bellas Artes show: intense, knotted pictures of injustice, greed and the dehumanizing power of technology. But even in those critical works, Rivera found something exalted in America, in the innovations of its scientists and the nobility of its working people.

The centerpiece of the show was “Glorious Victory,” a mural Rivera painted at the end of his life, after the American-backed coup that brought down the democratically elected government of Guatemala in 1954. It is pure propaganda, almost caricature, as Mr. Coronel says. The piece, on loan from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, will remain in Mexico at the Dolores Olmedo Museum for eight more months.

There are also exhibitions dedicated to Rivera’s watercolors, his very early work, his writings and his collections of pre-Hispanic art. A documentary at the National Museum of Art features silent footage of Rivera at work that was shot by the Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa.

At the end the film shows Rivera standing on a river bank, sketching Indian women as they bathe. Staged or not, the image is a reminder of what moved him first.

The national homage includes shows in Mexico City at the National Art Museum, munal.com.mx, through Feb. 24, and at the Dolores Olmedo Museum, museodoloresolmedo.org, through Jan. 2. |