Pain Transformed as Art

BYLINE BYLINE

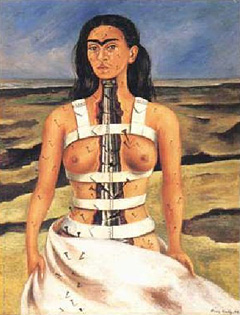

| | The Broken Column. 1944. Oil on Canvas. | | |

Often lonely, always in pain, possessed by a fierce love for her husband and her homeland, Mexican artist Frida Kahlo returned again and again to the subject she knew best — her own face and body.

Self-portraits painted over a lifetime are at the heart of “Frida Kahlo,” an exhibit opening Wednesday at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The first major U.S. exhibition of the artist's work in 15 years, it features 42 of her paintings, as well as a gallery of photographs of Kahlo and her husband, the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Though Kahlo, who died in 1954 at the age of 47, created highly personal paintings influenced by Mexican folk traditions, she is recognized today as an important modern artist, unflinching in the boldness of her vision and the emotional honesty of her work.

“What makes her so contemporary is her bravery in using the body as a site to explore identity, gender issues and sexuality,” says Elizabeth Carpenter, an associate curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where the exhibit originated.

Kahlo's paintings are full of blood, milk and tears, says Carpenter, during a preview at the museum. These messy fluids are powerful symbols of Kahlo's struggle to cope with pain, to live with her philandering husband and to find her place as an artist.

But Kahlo didn't become famous until nearly three decades after her death, when her unconventional life and the ferocity of her art turned her into a feminist icon. Art historian Hayden Herrera, whose 1983 biography helped propel Kahlo into the spotlight, says that when she began her research in the mid-1970s, Kahlo wasn't well known as an artist, even in her native Mexico.

“People thought of her as Diego Rivera's fabulous wife,” says Herrera, who is co-curator of the exhibit with Carpenter.

Kahlo was glamorous in an eccentric way, with her pulled-back hair and the bushy eyebrows that hovered like a great black bird over her face. She wore exotic jewelry and adopted the traditional Tehuana dress worn by women in Mexico's tropical Isthmus of Tehuantepec — colorful outfits with long full skirts and frilly blouses in flower-splashed patterns embellished with lace and embroidery.

The outfits celebrated the Mexican folk tradition Kahlo loved, but they also hid her disfigured right leg, the result of both a bout with polio as a child and a devastating accident at 18. When the bus Kahlo was riding in was hit by a streetcar, an iron handrail shattered her spine, hip and leg, leaving Kahlo with chronic pain and a broken body that would be invaded again and again by surgeons.

But the accident also opened a new world for Kahlo, who took up painting to fill her time while recuperating. She created portraits of herself and her family, and when she was up and about again, she showed some of them to Rivera, then a famous artist 20 years her senior.

Rivera told her she had talent, but the connection between them was about more than art, and they married the following year. Soon afterward, Kahlo accompanied Rivera to San Francisco and Detroit, where he made murals and she painted, drawing on the traditions of Mexican folk art to cope with her isolation and pain.

But what Kahlo created was something new, a mix of realism and fantasy, graphic in its imagery, yet imbued with the landscape and symbols of the Mexico she loved. Again and again, Kahlo turned difficult events in her life — loneliness, miscarriage, even her husband's affair with her sister — into inventive and powerful art.

“In a way, her self-portraits were a way of dealing with her pain, and also a sort of exorcism,” says Herrera.

A high-protein diet prescribed by one of her doctors became “Without Hope,” a painting that shows a bedridden Kahlo being force fed a bloody mix of animal parts and other disgusting stuff through a giant funnel. The steel corset the artist wore for several months inspired “The Broken Column,” an image of a naked Kahlo, pierced all over with nails, split open to reveal a crumbling column where her spine should be.

Yet even in the most gruesome of her self-portraits, and in the ones where the landscape behind her is dry and cracked open, like her worn and injured body, Kahlo's steady gaze shows a determination to endure. She wanted desperately to have a child, but never could, so she filled her house and her art with monkeys, parrots and other animals. She studied religion and psychology and supported revolutionary causes that kept her engaged with the world even as her body deteriorated.

“She did have a great zest for life,” says Carpenter.

And that's evident in the photographs that accompany the exhibit, which show Kahlo as a daughter and sister, a political activist, a patient and a wife, as well as an artist.

The photos offer a poignant look at the daily life of a woman who was a real person before she was an icon.

“They give you a feeling of Frida being here with us,” says Carpenter.

Betty Cichy can be reached at bcichy(at)phillyBurbs.com.

IF YOU GO

What: An exhibit of more than 40 paintings by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, including several never before displayed in the U.S., as well as more than 100 photographs from the artist's personal collection, with Philadelphia the only city on the East Coast to host the exhibition.

Where: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 26th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway

When: Wednesday through May 18; hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays, 10 a.m. to 8:45 p.m. Fridays, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays

Tickets: $20; seniors, students and ages 13 through 18, $17; children 5 through 12, $10; children under 5, free — the price includes general admission and an audio tour, and the tickets, which can be reserved in advance, are issued for a specific day and time.

Information and tickets: (215) 235-7469; www.philamuseum.org |