|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | April 2008 Entertainment | Books | April 2008

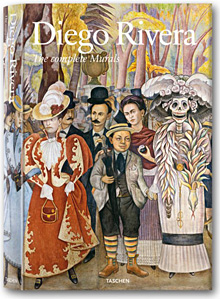

Diego Rivera: The Complete Murals

Jane Ure-Smith - The Sunday Times Jane Ure-Smith - The Sunday Times

go to original

| Diego Rivera: The Complete Murals

Lozano, Luis-Martín/Rivera, Juan Coronel

Hardcover 29 x 44 cm, 674 pages

ISBN: 978-3-8228-5177-7

Edition: Spanish

ISBN: 978-3-8228-4943-9

Edition: English

Check it out at Amazon.com | | |

What are we to make of the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera? Today, quite unfairly, his extravagant character and towering artistic achievement have become an adjunct to the story of his wife Frida Kahlo, the diminutive Mexican artist who, Sylvia-Plath-like, made art out of the drama of her psyche.

Rivera was a mass of intriguing contradictions. He was the revolutionary who missed the revolution. The cubist who invented a new figurative art in the name of the people. The communist firebrand who enjoyed commissions from the rich and famous. The champion of the workers who was fascinated by industry (many of his best works are dominated by machines).

“I am not merely an ‘artist',” he once said. “I am a man performing his biological function of producing paintings, just as a tree produces flowers and fruit.” A giant of a man, well over 20 stone for most of his adult life, Rivera had huge appetites (he was a notorious womaniser) and huge energy - not least in his work. Sometimes he would paint for days without stopping, taking his meals on the scaffolding and sleeping there as well.

Having sat out the Mexican revolution in Europe, Rivera returned home in 1921 to be “struck by the inexpressible beauty of that rich and severe, wretched and exuberant land”. It was as if, aged 34, he saw the place for the first time. Alongside the other two great Mexican artists, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, he embraced the cause of monumental public art and threw himself into two projects simultaneously.

One of these commissions - in the Anfi-teatro Bolivar of the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria - set a precedent for the controversy that would surround many of Rivera's projects. Egged on by conservative groups, the elite school's students rioted in protest at having murals inflicted on them by communists. Orozco and Siqueiros were dismissed and the minister of education resigned. Rivera somehow weathered the crisis, charmed the new education minister, and painted on - with a gun at his side. But it was the second project (the three floors of panels Rivera painted over four years at the ministry of education) that changed Mexican art history and catapulted the artist to fame. As his biographer Bertram Wolfe put it: “The series...made the Mexican artistic movement famous...as well as making Rivera famous in every corner of the western world. [It spelt] a resurrection of mural painting, dead since the Renaissance.”

The great pleasure of Diego Rivera: the Complete Murals, published last November in Spanish to mark the 50th anniversary of the artist's death - and now, finally, available in English - is that you can pore over every detail of the artist's work, the details you inevitably miss if you see the works in situ. It's a huge tome, and, at eight kilos, difficult to lift. The essays by Luis-Martin Lozano and Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera focus on Rivera's oeuvre chronologically. Although they lack structure and are written for the cognoscenti, they throw up interesting points - I didn't know that when Rivera added Mexican textiles to his cubist work, an impressed Picasso labelled him “exotic”. But the real reason to buy the book is its truly fabulous pictures: four-page foldouts of each mural plus endless pages of detail. In the ministry of education series, for example, we can zoom in on Frida Kahlo, installed in an arsenal, handing out weapons to both the proletariat and the Zapatistas. The ministry was where Diego met Frida. As a young artist she was determined to get his opinion of her work, so she pitched up and called him down from the scaffolding. They married a few years later.

By the early 1930s, Rivera was hot property north of the border. A solo show of his work at New York's MoMA attracted 57,000 visitors - and the commissions came thick and fast. Few were uncontroversial. The biggest storm blew up in 1933 when the Rockefellers commissioned Rivera to create nine murals for the RCA Building in New York. Rivera put forward a design and it was approved while he was working on murals in Detroit. A month later he went to New York, inspected the site for the first time - and radically changed his design to highlight the evils of capitalism. By all accounts he was expecting trouble and sure enough the Battle of the Rockefeller Center made headlines worldwide. When Nelson Rockefeller asked him to replace the face of Lenin with an anonymous individual, Rivera responded by offering to insert Abe Lincoln to balance things out. But he added: “Rather than mutilate the conception I should prefer the physical destruction of the composition in its entirety, but preserving, at least, its integrity.” That's exactly what happened. Rivera was sacked, work stopped and the murals were later destroyed.

Rivera retreated to Mexico, returning to America only in 1940. A decade earlier he had completed two murals in San Francisco: one at the Pacific Stock Exchange, the other the witty Making of a Fresco at the Art Institute, in which he depicts himself as the artist at work, his big backside facing us as he sits on the scaffold.

California had always welcomed him. So an invitation to go back there to create Pan American Unity (a panel of which appears above) for the Golden Gate International Exhibition seemed appealing. It became even more appealing when the Mexican police began to suspect Rivera of involvement in the first attempt on Trotsky's life led by Siqueiros. The actress Paulette Goddard (one of a long line of powerful, glamorous women who smoothed Rivera's path) helped him flee Mexico for California. In another panel of Pan American Unity, Rivera depicts himself and Goddard planting the tree of life - with Kahlo, palette in hand, partly obscuring him. This magnificent mural is today housed in a theatre at the San Francisco City College, and like its creator's reputation, it feels slightly neglected. One only hopes the Complete Murals gives both the boost they need. |

| |

|