|

|

|

Entertainment | Books | May 2008 Entertainment | Books | May 2008

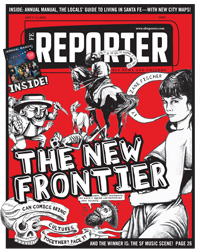

The New Frontier

Zane Fischer - Santa Fe Reporter Zane Fischer - Santa Fe Reporter

go to original

| | Cover illustrations by W. Schaff, R. Schuler, A. Thibodeau. Cover design by Angela Moore. | | |

In Eddy Robert Arellanoís bilingual historieta, a semi-autobiographical character heads into Mexico in search of romance and adventure.

In present day North America, Mexican nationals continue to enter the United States in search of fortune. Our two cultures mingle pointedly on the dilemma of educating our children for an uncertain future.

Historietas - pocket-sized comic books - have been popular and widely available in Mexico for many years, but Arellanoís may be the first hybrid historieta, bridging the US and Mexico on paper in a way that has yet to manifest in real life.

This week, Arellano - a New Mexico writer and teacher - speaks with SFR on these topics, as well as how comic books may help combat literacy problems, at the strange and poetic location of the Cities of Gold Casino in Pojoaque, New Mexico. SFR also presents Episode Three of Dead In Desemboque.

SFR: How were you first attracted to the comic form?

ERA: Iím a fiction writer and, actually, my first two novels were illustrated as well, if only sort of by accident, in what you might call a graphic novel or in-depth comic style. I was living in Providence, Rhode Island, where there is quite a large DIY artist scene. If you tell people that you are working on a book, they want to know how they can help out. And the talent pool is deep enough that, with a measly $200 advance, you can convince people to generate some quality illustrations.

The comic you are launching this month is in the tradition of the Mexican historieta, with a story by you and illustrations by three different artists.

I spent some time living in Mexico, in Desemboque for which the book is named, and guys would come buy selling stuff out of pick-ups. They advertise through loud speaker systems: milk, propane, water and this one guy selling these historieta comics, more commonly called semanales - weeklies. He was the libreria, literally the bookstore, and he sold new and used copies, all comics, out of the back of his truck. I got hooked on the delightful fantasy worlds, always sort of garish and often with eye-popping graphics, scenes of violence, sex and druggery. Itís almost always an Indian or a gringo who is the bad guy and, of course, there will be a Mexican hero. Eventually, I decided that I could emulate the form and tell my own kind of story. The first illustrator I approached with a script was William Schaff, who had illustrated one of my novels. He loved the idea, but I was asking for 100 pages of illustrations, which he couldnít do. We came up with two other artists to work on the project. It was this wonderful cross-continent collaboration. All of us went to Mexico and then the three of us decided on key image themes and went off to work on it for the next year.

I couldnít get a comic book publisher interested, although I didnít try too hard. Going with a publisher like Soft Skull has meant more of a book format, a kind of book tribute to comics, and not being able to keep the cost as low, but they embraced the graphic novel nature of it and itís worked well.

You also work as an educator as head of the Academy for Literacy and Cultural Studies for the University of New Mexico-Taos. It sounds as though youíve found a happy coincidence in the way your version of the historieta may be applied to literacy.

I canít say Iíve seen compelling pedagogical studies proving the value of such a thing, but some of the efforts and ideas of my peers have proven successful. In my own experience teaching English in Mexico and sharing some of the frames from the comic I wrote, Iíve noticed that the dual-language nature of it really makes things click for the students. I prefer Ďdual-languageí rather than Ďbi-lingual,í which has come to somehow mean teaching English to Spanish-speaking immigrants. Dual language implies a kind of equity. At any rate, comics are catching on. Thereís a project to design comic lesson plans at Columbia University and The New York Times has done a feature on comics in the classroom.

In graduate school, my own research was on corridos, the Mexican story-songs. Thereís something about storytelling in Mexico that lends itself to multimedia. A story can start out as a corrido and then become a comic and then a novel and then a film and then the story of all of that ends up being reincorporated into the corrido.

Something that seems possible with Japanese manga comics or, in this country, video games would be the narrative equivalent. Youíre suggesting that the popularity and adaptability of the medium lends itself to greater educational and cultural potential?

I guess thatís right. My drive as a storyteller has always been tied to a passion for promoting literacy. What called me to be a storyteller and to participate in the folklore is the same thing that called me to teaching. Now I do presentations on the historietas at festivals and conferences. Perhaps you know that the Denver Public Library has banned historietas on the grounds that they are violent and suggestive? Itís stifling the comfort, the excitement and the connection to home that a whole group of people were turning to the library to provide.

We can agree that nothing should be censored, but when youíre busy championing historietas at conferences and festivals, does anyone challenge you based on the fact that these comics tend to reinforce sexist, racist, macho, violent stereotypes?

Actually, Iíve not really had questions that pointed. But you asking that makes me see that my colors are populist. There are verifiably millions of people in Mexico and points south, and many, many more all over this country who are reading these historietas each week; it is what they find comfortable as their contemporary literature.

But television has a tremendous audience as well. Just because shows are popular doesnít mean they are productive or have cultural value beyond glorifying violence and distorting sex.

Thereís where my own conscience kicks in. I made Dead in Desemboque as a family comic. I feel that people of all cultures and age groups can pick it up and, you know, maybe a couple of stray Tecate cans is about as racy as it gets.

Well, thereís knife fighting, nudity, prescription pharmaceuticals...

OK, thatís true, but the Xanax is a simile. It says Ďlike Xanaxí not that it is. And there is semi-nudity, especially in the one scene that implies a sort of a bacchanal but, you know, thatís life, and itís a consensual bacchanal.

Except for the fact that the protagonist is bound and gagged during the scene. But I think what youíre getting at is a fundamental difference between reading and watching television, leaving aside, for the moment, the subject matter. Are there Ďcompelling pedagogical studiesí that demonstrate that reading is better?

Iím certain that there are, but for now, Iíll just say that for myself and my peers, the evidence is experiential. We work with kids all the time who are getting shorter attention spans, who have poor writing skills, poor communication skills all around. My parents always told me to read and the reason, I think, is that there was so much to imagine, all the pictures, everything left unsaid or hinted at. Itís an active process, whereas thereís something awfully passive about the television experience. Iíve seen the way my own 2-year-oldís eyes glaze over when sheís dropped in front of a giant flat screen TV and, well, what a strange thing that happens synaptically. I spent my own youth reading Mad Magazine and all kinds of stuff that wasnít highbrow and wasnít necessarily in good taste, but it still fed me, still led to the development of critical thinking which, I would say, is a key to literacy.

And literacy is still fundamental?

People say that weíre now in the Information Age. If so, the single most important currency is communication. And weíre not all sitting around chatting through wristwatch video displays - written communication is more important than ever. To read text and to communicate in script is power in the information age.

You talked about dual-language as a kind of interpretive equality in the comic. Do you see the potential for a cultural product that illuminates the contemporary complexity of the intersection between the US and Mexico, something that really navigates life on la frontera?

Thatís the kind of optimism I like to embrace. I want it to be true that such a thing could happen. But you know, thereís the physical border, which I do think of as la frontera, the frontier - it sounds like a place you go toward rather than something that hems you in - and then thereís the more real border that exists in pockets here and there. The border is in Santa Fe, in Taos, in Chicago, itís amorphous and constant and fuzzy but it is full of the kind of stories that need to be told. Maybe we do need a border comic project here, it could be a powerful tool for depolarizing the region. More than ever my job demands thinking up new ideas to, I donít want to say trick, but it is trickery in the best sense, in the way that my teachers coaxed me into engaging ideas that may have seemed suspicious or useless to me at firstÖbut if the result is having people excited about storytelling, which means believing that each life has a good story, well, letís just say Iíve got that educatorís faith. |

| |

|