|  |  |  Entertainment | Books | July 2008 Entertainment | Books | July 2008

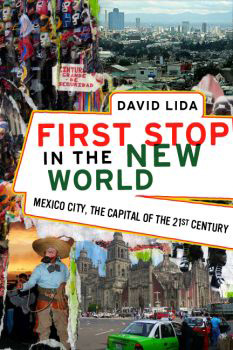

First Stop in the New World

Mary D'Ambrosio - SFGate.com Mary D'Ambrosio - SFGate.com

go to original

| First Stop in the New World

Mexico City, the Capital of the 21st Century

by David Lida

Riverhead; 336 pages; $25.95 | | |

You might expect a boosterish screed, a mocking polemic or at least globalization theory from so grandiosely titled a book. But in "First Stop in the New World," author David Lida mostly eschews forecasting in favor of clear-eyed, agenda-free journalism, grounded in old-fashioned street reporting.

Thank God he's stubborn. As Joseph Mitchell captured life on the margins of midcentury New York, Orhan Pamuk the melancholia of 20th century Istanbul, and Martha Gellhorn civilian suffering in Civil War Spain, Lida masterfully details the plight of a struggling and repressed city with nowhere to go but out.

Nothing fundamental has changed since the North American Free Trade Agreement, or really for the past couple of decades, except that a Mexican, Carlos Slim Helú, has surpassed Bill Gates to become the world's second-richest man after Warren Buffett. Mexico is unarguably richer today - its per capita gross domestic product the second highest (after Brazil) in Latin America - but, surprise, those funds haven't been spread around. Some 50 percent of Mexico City's population still lives in poverty, and only 12 percent of workers earn more than $23 a day. Though few are destitute, for the vast majority life is still uncomfortable and abusive, governed by long work days, iffy public services, petty rip-offs and kidnapping threats. The ambiance is one of cynicism, sexual repression and hopelessness.

Lida cites Octavio Paz's description of Mexicans as suffering from a chronic mistrustfulness, an inferiority complex and an outward servility that disguises cunning, resentment and a lust for revenge. When you work for someone else, according to the reigning belief, your prospects are nil: You'll never get a raise, and are expected to keep shoulder to wheel until you die or are discarded (as Lida himself discovered when he took a publishing job and couldn't get a raise during his 3 1/2 years there.) A job is such a raw deal that Lida sees the 35 percent of workers who participate in the informal economy as having made the smarter choice.

Here he is on social relations: "Indeed, in Mexico City, where social divisions can be as pointillistic as in England, and a caste system is as firmly in place as in India, people with money perceive the poor as abstractions, blurs who only come into focus when they wait on them. The woman who comes to clean your home, the man who hands you a towel after you've washed your hands in the restroom, the guy in the yellow jumpsuit who sells you a phone card at the traffic intersection - you are certain these people exist because they've interacted with you."

In other words, he writes about the Mexico City you'll recognize, whether you visited recently, emigrated a generation ago or absorbed your sense of it from a Carlos Fuentes novel. If globalization is bringing something newer and better, in his view, it's probably the mixed blessing of housing (more condo developments and more sprawl) and Wal-Mart (decried by intellectuals but joyfully welcomed by the ripped-off working class).

In search of the soul of the modern chilango (a sometimes mocking slang term for a resident of the central Distrito Federal), Lido diligently covers the bar scene in all its variations: He tours cantinas and cabarets, lap-dancing joints and swingers clubs, and visits one of the few remaining pulquerias, a bare-lightbulb room where old men go to imbibe pulque, the cheap national drink made of fermented cactus that has a texture "somewhere between spit and sperm."

He also devotes plenty of ink to sexual mores, which in his telling puts Mexico City closer to Victorian England than to swinging Rio. It's a buttoned-up town where the women won't show cleavage or even wear dresses, he says, partly because men of every class ogle, goose and generally treat them like "wampum," just as their forebears offered up their women to the conquering Spanish five centuries ago. Nonetheless, a grave national case of Madonna/whore complex helps keep an astonishing 78 percent of Mexican men and 71 percent of women sexually dissatisfied.

We meet odd, compromised and tragic characters: a man who played Jesus in the neighborhood passion play; an alcoholic painter; a drugged-up street kid; and two panicky carjackers who tried to take Lida and his then-wife hostage. But Lida is no Bernard-Henri Lévy, touring the freaks and retreating to write, and gloat, from the safe distance of a more sophisticated society. He's a New Yorker who fell in love with Mexico City and moved there in 1990, and has been living and writing there more or less ever since. Perhaps it's a love of the repressed Mexican kind - as readers will need to search zealously for even a glimmer of affection for the place. I found myself wondering why he stayed. Besides what sounds like a great community of friends, maybe it's the street food, which comes in for the book's most lavish praise.

The lingering question is, why, then, does he think Mexico City to be the capital of the 21st century? Citing predictions that this will be a century of both emerging markets and supercities, Lida suggests that because Mexico City is both, it's "poised to be part of the vanguard of this century." Mexico is arguably the "capital of the Spanish speaking world," so "it is increasingly relevant for Americans to have some inkling of how Mexico City works." Ugh. World Bank tomes are more convincing. Fortunately, Lida's soon back in his more enjoyable critic's mode: "What will the future of Mexico City look like? Predictions often sound like something that Philip K. Dick dreamed up after swallowing a fistful of amphetamines."

You'll want to read "First Stop in the New World" for its great journalism - for the unvarnished off-the-grid tour Lida provides; for the singers and hustlers and artists you'll meet; and for the insight you'll develop into an ancient, booming but seriously ailing metropolis. But you can pick up the next big globalization theory from the pundits. {sbox}

Mary D'Ambrosio is the founding editor of the forthcoming Web magazine Big World. Email her at books(at)sfchronicle.com. |

|

|  |