|  |  |  Entertainment | Books | December 2008 Entertainment | Books | December 2008

Beyond Reach: Frida Kahlo and Salma Hayek

Ed Hutmacher - MexicoBookClub.com Ed Hutmacher - MexicoBookClub.com

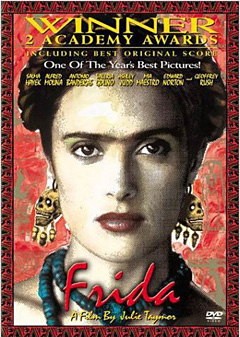

| | In 2002, Salma Hayek played a very foxy Frida Kahlo in the award-winning movie Frida, itself an adaptation of Hayden Herrera’s book Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. (MexicoBookClub.com) |  |

In 2002, Salma Hayek played a very foxy Frida Kahlo in the award-winning movie Frida, itself an adaptation of Hayden Herrera’s book Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. This practice of mixing cinema with literature is risky, and probably accounts for why I have a problem understanding women in general and these two superstars, Salma and Frida, in particular.

Perhaps the confusion is just another indication of how wide the communication rift is that divides men and women — a Mars and Venus conundrum that's beyond the reach of male comprehension. Cosmic forces abound in the movie, making the alien fog surrounding the female species more obscure. Frida Kahlo and Salma Hayek are otherworldly women. And when worlds collide, I start asking questions.

Should I esteem Frida Kahlo for her artistic talent, her intellect, because she was a real heroine of her times — a Latina who refused to settle for the passive role Mexican society required of women?

Should I feel sympathy for her because of the horrific physical afflictions she suffered most of her 47 years, and then be inspired by the never-quit attitude that enabled her to still live a remarkable and productive life?

Women answer that I should feel all of these, and more. I do.

I didn’t read Herrera’s biography before I saw the movie and knew only a little about Frida Kahlo — mostly that she was an eccentric and popular Mexican artist. One can’t venture far in Mexico without seeing something emblazoned with "Frida" on it, like clothing, beach towels and coffee mugs. Prints of her art hang in restaurants and in stores, and bars named in her honor can be found just about everywhere, all adorned with Frida trappings.

It’s not only in Mexico where "Fridamania" reigns. Salma's 2002 biopic helped propel Frida Kahlo to international fame and, along with it, cult-like status. In the United States a postage stamp bearing her image was issued, joining her with pop celebrities Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley as immortal cultural idols.

But after seeing the movie, I know a lot more about Frida Kahlo. And that is largely due to Salma Hayek, whose performance was as fantastic as the flesh-and-blood Frida was surreal. Salma happens to be one of the most beautiful people to grace modern cinema, so I was easily captivated by the unfolding drama of Frida’s life and times. It didn’t hurt that Salma takes off her clothes and cavorts in making love with a variety of partners from time-to-time, including her husband, the legendary muralist Diego Rivera.

In the chronicles of notable Mexican women, Frida Kahlo stands out. She was a remarkable product of Mexico’s post Revolutionary 1920s and 1930s — a period of artistic and political renaissance in Mexico — and a genuine protagonist for a country lacking of popular heroines.

As a child, she dealt with the misfortune of contracting polio. At 18 or 19 (the age varies by different accounts,) she suffered gruesome injuries from a trolley accident that required multiple operations and several years of agonizing recovery.

During the long recuperation Kahlo taught herself to paint and later took some of her art to Diego Rivera for his opinion (a telling moment in her saga, testifying to the bravado that shaped her whole life.) Impressed with the young woman and her talent, Rivera encouraged her to continue in her artwork. Later, he married her.

Kahlo and Rivera’s marriage was fraught with emotional turmoil. She also endured the never-ending agony of physical degeneration and repeated surgeries. The anguish she experienced is unimaginable. But from somewhere within, deep in downcast crevices few of us have had to mine, there arose an indomitable grit to persevere. Her resolve and talent triumphed over her torment.

Since her death in 1954, Fridamania has grown stronger and brighter. The movie and Salma Hayek’s performance threw fuel onto the fiery fame, depicting Kahlo to be a woman of independence, courage and nonconformity. Thunderous ovations from women around the globe resounded. Men, including me, joined in the accolades, but not without trepidation.

The movie is full of issues women have been clamoring about for decades: education, equality, freedom of expression, self-determination, love, marriage, sexuality, and politics. Herrera’s 1983 biography reintroduced Frida Kahlo to a public in the midst of social movements advancing the political discourse on multiculturalism and Feminism.

Frida — the fierce, funny, talented, bisexual Mexican communist who was twice married to the same philandering husband — seems to have been adopted as a new kind of role model for women. When the movie was released two decades later, I couldn’t make up my mind whether to regard Selma’s Frida a feminist centerfold or a fascinating weirdo.

I was surprised that one of the movie’s two winning Oscars was awarded for Makeup (the other for Original Score) because no matter how much effort was expended to make Salma look like the androgynous Frida, the persona of the renowned artist that appeared on the big screen oozed sex appeal. Hayek created a full-bodied character with a definite lust for life. Salma as Frida was a pleasure to witness.

This combination of Frida (artist-communist-historical figure) and Salma (actress-capitalist-sexy babe) made me second-guess who was being portrayed and what message was being communicated. Had Frida been transformed into a neo-feminist icon?

Most of the men I talked with, Mexican and others, were as enthralled by Hayek’s portrayal of Kahlo as I, but not much was discussed beyond Salma’s sexy attributes. Was that the impression of Frida Kahlo men were to take home after watching the movie—anguished sex nymph?

What was the director, Julie Taymor, and the co-producers (five of seven were women, including Salma) hoping to accomplish with this movie? Salma’s lusty performance eclipsed the more important elements of Frida’s life, such as her art, her identification with Mexican folkloric traditions, and her political advocacy for the common people. I thought women wanted men to move beyond the realm of superficial sexism.

Frida Kahlo is also a riddle, of sorts. Apparently, she fudged on her age throughout her life, claiming she was born a few years after the fact. An inscription painted on the wall of her childhood home in Coyoacan corroborates the date: "Aquí nació Frida Kahlo el dia 7 de Julio de 1910" (Here Frida Kahlo was born on July 7, 1910.)

But according to biographer Herrera, "her birth certificate shows Frida was born on July 6, 1907. Claiming perhaps a greater truth than strict fact would allow, she chose as her birth date not the true year, but 1910, the year of the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution."

It’s quibbling to call someone on shaving a few years off their age, but Herrera thinks there’s more to the hoodwink than vanity. She writes, "The inscriptions, then, are embroideries on the truth. Like the museum itself, they are part of Frida’s legend... She decided that she and modern Mexico had been born together."

The making of legends (or movies) and the sifting of fact from myth are not mutually compatible endeavors. Other writers on Kahlo point out that she was more than just a creative artist; she was a calculating promoter extraordinaire. How so? Well, the movie doesn’t address such matters. For the viewing public; another Frida is presented.

More appealing to moviegoers are the intriguing themes found in her relationship with Diego Rivera. Addressed are issues of anger and jealousy, of indifference and deep affection — is it love? – of loyalty and fidelity; that’s the kind of fodder the paying public feeds on at the movies.

They were an odd looking couple, too. Diego was mammoth and sloppy in his paint-stained overalls and huge miner’s shoes while Frida was small and petite, often choosing to dress in colorful folkloric costumes from the region of Tehuantepec. In the movie, Frida’s mother disapproved of their marriage, calling it "the marriage of an elephant to a dove."

"It’s not a story about falling in love," said actress-producer Salma Hayek in an Entertainment News Wire interview at the time of the movie’s release. "It’s a story about staying in love."

Okay, so now we know that the movie was meant to be some kind of love story and not necessarily a biographical one, which are not as popular with the general public, said Salma, because "they’re not as romantic." That’s okay by me because these two lovers are very different from the rest of us, which helps make the movie fascinating. What screenwriter could invent characters like these two?

Both Frida and Diego share passionate natures, a kind of chic bohemian lifestyle and an equally strong commitment to art and radical politics. Their circle of friends included socialist-communists like the renowned Italian photographer Tina Modotti, the painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, and the exiled Russian communist Leon Trotsky. Yet the movie touches lightly on such weighty stuff and defers to the steamy relationship between husband, wife and their assorted lovers.

Rivera is an overweight philanderer and does some slimy things, like having sex with Frida’s sister. I wondered if this unrestrained sexuality is typical of Mexican men, then or now. I’ve read and been told that it is — that too many Mexican men still hold to a machismo attitude that manifests itself in womanizing.

But wait a minute! Wasn’t the sister a willing participant? What does that say about her? Still, Rivera’s sexual escapades seem to exist apart from his devotion to Frida. And Frida is no victim in the film or Herrera’s book.

Ed Hutmacher is Editor in Chief of Mexico Book Club. For more information on books about Mexico, please visit the website at MexicoBookClub.com. |

|

|  |