|  |  |  Entertainment Entertainment

Updating the Cohiba

Nick Foulkes - Newsweek Nick Foulkes - Newsweek

go to original

January 16, 2010

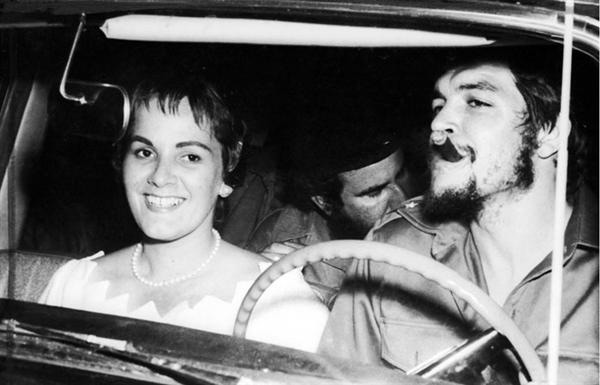

| | Che on his honeymoon in 1959. (Bettmann-Corbis) |  |

It is a warm and slightly sticky late November afternoon inside the early-20th-century mansion that houses the global headquarters of Habanos SA, the body that markets Havana cigars. Fierce sunlight negotiates the fragrant blue cigar smoke and falls onto the boardroom table along with a sudden silence. I have just uttered two words that seem to have the magical power of a Harry Potter incantation: medio tiempo. In the Cuban cigar industry, this refers to a pair of small leaves at the very top of the tobacco plant - and not just any tobacco plant, but a talismanic, semimythical variety that in the past was used only occasionally. Accordingly, true cigar devotees reserve a room-silencing reverence for these hallowed leaves.

To be fair, I had never heard of medio tiempo until earlier that day, when I discovered during a tour of El Laguito factory that these leaves formed part of a new blend being reintroduced in that most revolutionary of brands: Cohiba. Before the distinctive black-and-yellow band of the Cohiba became a badge of plutocracy, it was the favored smoke of Cuba's revolutionary elite. The story goes that in 1963, Castro's driver was sitting in El Comandante's Oldsmobile enjoying a cigar rolled for him by a friend. Castro was so impressed by the lingering aroma that he asked for one. He enjoyed it enough to have its roller, Eduardo Rivera, summoned from his torcedor's bench and entrusted with the solemn responsibility of rolling the leader's cigars. For security reasons Rivera was moved between factories and sometimes rolled cigars at home; even when a factory was established to make Cohibas, it was a high-security site due to rumors that the CIA was pondering the deployment of an exploding cigar against the Maximum Leader. To this day, an aura of secrecy surrounds the brand, and it remains by far the most difficult cigar factory to visit. That fact that, like all Cuban cigars, Cohibas cannot be legally imported to the U.S. only adds to their mystique.

Soon these long, elegant cigars became as much a part of the revolutionary look as facial hair and military fatigues, thanks to Che Guevara's pronouncement that he had never smoked a better cigar. They were named Cohibas after the Taino Indian word for the bunched tobacco leaves that Columbus first saw the island's inhabitants smoking.

Today Che is dead, Castro no longer smokes cigars, and Cohiba has gone public, accounting for about 20 percent in value - but only 12 percent in quantity - of the country's annual cigar production. There are now more than a dozen different sizes of Cohibas, ranging from the anorexic Panetela to the chunky Siglo VI. What accounts for Cohiba's reputation (and its price) is the quality of the tobacco harvested from the five best plantations in the Vuelta Abajo area and the extra fermentation of the filler leaves, which provide a cigar's flavor. While the leaves in ordinary cigars are fermented twice, those used in Cohibas are fermented three times, lowering the acidity and nicotine content and enhancing the smoothness.

But how do you make the best better? This was the question facing Cuba's cigar industry as it sought to appease aficionados who longed for a richer, larger cigar. Until recently, conventional wisdom held that Cuban cigars should be filled with three types of tobacco leaves. The volados, which have little flavor, are at the bottom of the plant, and their primary function is combustibility. Seco leaves from the middle of the plant impart some flavor and aroma, while the ligero leaves, which come from the plant's top, are responsible for a cigar's power. To this triumvirate, we must now add medio tiempo as the fourth and final tier.

The first handmade postrevolution cigars containing medio tiempo will make their debut next month, with the launch of the hefty Cohiba Behike. The diameter of a cigar is determined in ring-gauge points, each of which is 1/64th of an inch. The original Cohiba, the Lancero, is a 38-ring gauge; by contrast these new Behikes are available in only 52-, 54-, and 56-ring gauges in ascending lengths - in other words, L, XL, and XXL sizes. While in Cuba, I was fortunate enough to taste one of these monsters, on the understanding that this was an experimental cigar and that the blend still had to be finalized.

In addition to a slightly dislocated jaw, I came away from the encounter with a renewed respect for the Cohiba brand. The surprise is that for all medio tiempo's much-vaunted strength, this was not an overpowering cigar; instead it had all those wine-tastery notes of cedar wood and vanilla, delivering its subtle flavors with a delicious rounded creaminess. The Cohiba Behike will be made in very small numbers, and for aficionados of the Havana cigar it will deliver an almost religious experience. So the most fitting description I can find is in the Old Testament Book of Judges, which perfectly sums up the appeal of the Behike with the words "Out of the strong came forth sweetness." |

|

|  |