|

|

|

News from Around the Americas | January 2006 News from Around the Americas | January 2006

Fear and Loathing on US's Lawless "Third Border"

Bernd Debusmann - Reuters Bernd Debusmann - Reuters

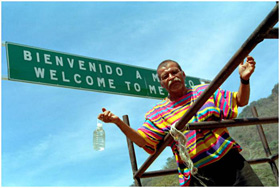

| | The Mexico-Guatemala border. (Hans Hendriksen) |

ecun Uman, Guatemala - This dusty frontier town caters to smugglers and illegal migrants. It's a stone's throw from Mexico, across the brown waters of the Suchiate river. In a way, it is also the southernmost border of the United States.

"Make no mistake, this river is not an obstacle, none whatever," said Father Ademar Barilli, a Catholic priest who runs the Casa del Migrante, a hostel for migrants.

"The obstacle is across the river. The Mexican government has turned all of Mexico into a frontier. They are working on behalf of the U.S.. They are hunting migrants."

This is a common argument in Central America though one would not hear it in Washington, where the border with Mexico has moved into the center of a heated debate. In December, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep illegal immigrants out.

Mexico has made clear it feels it efforts to stem the tide of illegal migration have not been properly appreciated. Statistics issued by the country's National Immigration Institute explain why: in 2000, Mexican authorities deported 105,902 illegal immigrants, almost all of them Central Americans. In 2005, the number rose to almost 250,000.

In comparison, the U.S, Border Patrol reported 1,188,997 apprehensions in 2005 along the U.S.-Mexican border, which is the world's most frequently-crossed international line and more than three times as long as Mexico's border with Guatemala.

The crackdown in the south, combined with tighter visa requirements for foreigners traveling to Mexico, responds to U.S. pressure, diplomats in Washington say.

"They (the Mexicans) are treating us badly," said David Gonzalez, an 18-year-old Salvadorean who said he was arrested in Tapachula, 20 miles north of here, and deported back to Tepuc Uman after three months in jail. "Many fear them more than they fear the gringos (Americans)."

A string of complaints about mistreatment of U.S.-bound Central Americans prompted Mexico's National Human Rights Commission to launch an investigation into conditions in the country's 119 migrant detention centers.

The biggest such center in the Western Hemisphere, for 1,450 people, is nearing completion in Tapachula.

"Sad Contradiction" In Mexican Policy

The commission's report in December painted a bleak picture of overcrowded, unsanitary facilities reeking of excrement where detainees are forced to sleep on bare floors, go hungry and lack medical care.

When he introduced the report, commission president Jose Luis Soberanes described as a "sad contradiction" that his government was asking the U.S. to respect rights for Mexican migrants that Mexico was unable to guarantee to migrants on its own border.

Thousands of Central Americans illegally cross the 600-mile

border between Guatemala and Mexico every day on a long and dangerous trek toward the U.S., part of a global mass movement driven by a steadily widening gap between rich and poor countries.

The number of international migrants doubled between 1985 and 2005, now stands at 200 million, and is expected to increase, according to the U.N.'s Global Commission on International Migration,

The United States is the world's top destination for international migrants, legal and illegal.

A way station on the route to the U.S., Tecun Uman provides an array of services - some legal, most not - to a floating population of migrants whose number often matches that of the 28,000 residents.

The town's main square serves as an exchange for information and goods, from forged documents to cigarettes sold singly to those short of cash. Bars with names like Las Vegas and Starlight along Third Street beckon male travelers with money to spare.

Most bars do double-duty as brothels, staffed by young women who ran out of money and out of luck on the way north. By some counts, there are 80 brothels in Tecun Uman and about 1,000 prostitutes, many lured into conditions of indentured slavery, according to church organizations trying to help the women.

Migrants As "Humans Without Rights"

The most prominent organization helping migrants is Barilli's Casa del Migrante, which gives daily briefings to border crossers with practical advice on routes, clothing, medicine, food and their rights if arrested.

"Police and other authorities see them as humans without rights, " said Barilli, who worked with migrants on the California-Mexico border before moving to Guatemala 11 years ago. "Everybody preys on them."

Some 16,000 people passed through the Casa del Migrante in 2005, up from 14,400 the year before despite the fact that the freight train to the border - the migrants' preferred means of transport - stopped running after Hurricane Stan devastated Guatemala in October.

Since then, crossing points along the border which zig-zags through the rugged mountains north of here - an area virtually impossible to control - have absorbed some of Tecun Uman's traditional traffic.

By the time migrants reach the border, many have already been raped, robbed, beaten and forced to pay bribes by corrupt policemen and marauding criminal gangs.

None of this deters people in search of a better life.

"The wall won't stop them," said Barilli, who speaks from experience. He worked in California when the U.S. constructed a 14-mile steel wall between San Diego and Tijuana.

"Mexico's roadblocks, detentions and deportations won't stop the flow either. What is needed are concrete measures to end poverty and improve living conditions in the countries from where the migrants are leaving. That's not happening." |

| |

|