|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | April 2006 News Around the Republic of Mexico | April 2006

Making American Money at Home in Mexico

nuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post nuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post

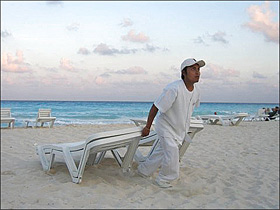

| | Elias Chi Quetzal moved with family to work as a beach attendant at the Grand Oasis Hotel in Cancun, Mexico. Workers who once chanced crossing the U.S. border illegally for jobs increasingly are migrating to Mexico's tourist-rich areas, far from U.S. Border and debate on immigration. (Manuel Roig-franzia/The Washington Post) |

Cancun, Mexico - There was a time when Jose Luis Luevano could envision making real money - feeding-the-family, paying-the-rent money - only in El Norte, or the United States.

Every nine months or so, he stuffed a backpack at his home in San Luis Potosi, a sooty industrial town at the northern rim of Mexico's high central plateau, and went north. He liked the cash he earned when he slipped illegally across the border. But he hated the journey. And he hated being away from his family more.

Then, six years ago, someone told him about Cancun. Real money could be found there, too, they said. American money without having to go to the United States.

He never went to El Norte again.

Luevano, 30, a taxi driver who also operates a small catering business here, is still a migrant, but a migrant of another sort. While President Bush met last week with his Mexican counterpart, Vicente Fox, in this seaside resort, tens of thousands of Mexican migrants drawn here by the promise of a steady paycheck drove the cabs, served the tropical drinks and managed the front desks.

These workers are simultaneously dependent on the United States, for the tourists who make this place a huge economic engine, and independent from their richer northern neighbor, because they don't feel the need to leave their country to make a living.

"Why would I want to go to the U.S.? To die in the desert?" said Alejandro Corrato Orozco, a security guard with mutton-chop sideburns at the Grand Oasis Hotel, who spends his days pacifying drunken U.S. college students. "Mexico - Cancun - is a land of riches. I like these Americans, but I don't want to live in their country."

Cancun is a place where attitudes toward the United States are far different, and far milder, than in the anxious border towns that form the dominant image of Mexico during this time of immigration controversies. News of U.S. immigration battles - followed in screaming-headline detail in other parts of Mexico, particularly in border towns and the capital, Mexico City - barely registers. Corrato and Luevano, like many of their co-workers, had not noticed that the U.S. Senate was debating an immigration bill last week, a development that their countrymen in border towns such as Mexicali and Nogales tracked obsessively.

In many ways, Cancun is the great dream of Mexico, one of the few places in the country where there are enough decently paying jobs that few contemplate risking an illegal gambit into the United States. For three decades, this city and the Mayan Riviera towns to the south have been a magnet for workers throughout Mexico, now employing more than 200,000 people, many of whom opt to come here rather than go to the United States.

Few get wealthy working in Cancun's tourism industry, but the jobs usually provide money for a respectable standard of living in a region where the cost of housing, food and services is low. And workers come without the danger of deportation faced by those who illegally enter the United States. Fox declared recently that the United States would someday "beg" Mexico for workers, and his ministers point to places such as Cancun to support that argument.

"We don't want to go there, to the U.S.," said Gabriela Rodriguez, the secretary of tourism for the state of Quintana Roo, which includes Cancun and the Mayan Riviera towns. "We want the U.S. to come here. Here, it's the reverse."

That reverse perspective was obvious from the moment Bush arrived in Cancun. Heavily armed police officers lined the roads, mindful that hundreds of thousands of Latinos rallied last week in Los Angeles, Phoenix and other U.S. cities. But there were almost no protesters to hold back, just a ragtag cluster of a couple of dozen bandana-wearing men and a few tourists banging drums in downtown Cancun.

Juan Lopez Hernandez, an accountant with heavy-lidded eyes, barely looked up as the protesters clattered past the canopied shoeshine stand outside Cancun city hall where he was waiting to have his loafers spruced.

"Look, we respect the United States," said Lopez, who left the Mexican state of Tabasco eight years ago to work in Cancun. "We are good neighbors."

Cancun's gaudy strip of high-rise hotels - some in the shape of pyramids and built on a road named for the Mayan feathered serpent god, Kukulcan - is the invention of promoters of tourism in Mexico's late-1960s government. The city was a sleepy fishing village until the government audaciously built a major airport and began cutting deals with hoteliers. In 1974, the first of the big hotels opened in the city, starting a building frenzy that has led to 27,000 hotel rooms here and another 25,000 in the towns to the south. The area generates $4.8 billion a year in revenue, accounting for one-third of the country's second-largest industry.

The region's importance was demonstrated by the hyper-speed government response to the devastation wrought in October by Hurricane Wilma, which smashed hotel windows, shredded palapas - the area's distinctive thatch-roofed cabanas - and punched holes in roofs. A public-private partnership ensured workers they would receive at least minimum wage while the hotels were repaired, although they lost substantial income from tips. None was fired, tourism officials said. Now nearly 18,000 of Cancun's 27,000 hotel rooms are operating, and work crews swarm at more than a dozen hotels that have yet to reopen.

Luevano makes more money here, much to his surprise, than he did hammering nails in Houston suburbs. Between his taxi business and his catering shop, he takes home $1,000 a week, almost double what he made in the United States. At his home in Puerto Moreles, south of Cancun, the children and grandchildren of American and Canadian neighbors - many of them retirees lured by the low cost of living - are always stopping by because they love his wife's quesadillas. The grown-ups, he said, seldom talk of guest-worker proposals or border patrol agents.

"It just doesn't interest us," Luevano said. "If you want to work every day here, if you want to work seven days a week, and work overtime, you can do it. There is more than enough work."

There's a saying in Cancun that anyone under 30 here surely came from someplace else. Even Rodriguez, the secretary of tourism, moved here from another part of Mexico. Her friends and neighbors don't dream of leaving Mexico. They dream of staying. Rodriguez has dreams, too: more big hotels, stretching across thousands of miles of spectacular, undeveloped Mexican coastline. "A curative," she called it, for Mexico's ills.

As she talked, her eyes glowing, buses let off loads of young Mexican men and women outside the hotels on Kukulcan Avenue. They all had backpacks. In other places that would be a sure sign of migrants headed to El Norte. Here, they are college students from the university in downtown Cancun, transported across a swamp to the hotel zone, where they train for careers in the hospitality industry and where foreigners fill their pockets with pesos.

They grew up in Michoacan and Villahermosa and Chiapas. But they have come to Cancun to stay. |

| |

|