|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | August 2006 News Around the Republic of Mexico | August 2006

Mexican Park's Patrons Try to Outwit 'La Migra'

Marion Lloyd - Houston Chronicle Marion Lloyd - Houston Chronicle

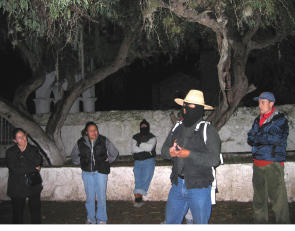

| | Alfonso Martinez, with hat and ski mask, gives a pep talk before leading visitors on a 4-hour night trek that simulates the experience of crossing the Rio Grande. (Marion Lloyd/Chronicle) |

El Alberto, Mexico — "Run! They're on our tails!" shouted a man in a ski mask as he led 15 people down a steep ravine and into a thorn-infested thicket.

Gunshots pierced the night air. Sirens wailed. Then came a voice, sounding like the Border Patrol. "Don't cross the river!" someone yelled in a heavy accent. "Go back to Mexico where you belong!"

Welcome to one of Mexico's strangest tourist attractions:

A park where visitors pay $15 to hike across fields and through treacherous ravines, a grueling experience aimed at simulating an illegal journey across the U.S.-Mexico border.

"We want this to be an exercise in awareness," said Alfonso Martinez, who acts as the chief smuggler at EcoAlberto Park in central Mexico. "It's in honor of all the people who have gone in search of the American Dream."

The park, funded in part by the Mexican government, compares crossing the border to an "extreme sport" and tells participants that they, too, can "trick the Migra," slang for the Border Patrol.

Real-life agents are not amused.

"If this is about training, obviously that's not anything like what they will experience when they cross the border," said Xavier Rios, a Border Patrol spokesman in Washington, D.C., pointing out that most migrant journeys last for many days, not hours.

He also criticized the organizers for re-enacting an illegal and dangerous activity — and profiting off that.

"This doesn't seem that it's conducted in an appropriate manner," he said.

Martinez and others are undaunted, saying that the experience gives people a better understanding of the risks migrants take.

Every year, some 500,000 Mexicans cross illegally into the U.S., a perilous journey that has claimed more than 2,000 lives over the past decade. Many die of heat exhaustion, while others drown in the Rio Grande.

Plight of the Indians

Residents of El Alberto, a Hñahñu Indian village 120 miles north of Mexico City, know the dangers. Most of the townspeople — up to 90 percent, by local estimates — have ventured across the border illegally. And like most of the town's 2,500 residents, Martinez is a veteran.

He nearly died after he got lost in the Arizona desert in 1999 and readily concedes that the tours are far from realistic.

But, he says, "They let people get a glimpse of the suffering that migrants endure."

He also uses the tours to educate visitors on the plight of Mexico's 10 million Indians, who are often treated as second-class citizens by the country's mixed-race majority.

"The colonizers stole everything but our soul," said Martinez, who blends philosophy with off-color jokes during the mock crossings.

Patricia Ávalos, a computer technician from southern Campeche state, joined him for a trek on a recent Saturday night.

"I want to experience what my people suffer," she said before setting off from the village's main church. "I don't plan to cross, but at least this gives me an idea of what it must be like."

And it was no picnic.

Led and sometimes taunted by six guides in ski masks, the participants slogged through muddy bogs and dense underbrush, scampered along the top of 10-foot stone walls and hid out in cornfields.

"No weaklings allowed," one guide said.

The visitors also bounced around in the back of pickups racing along rock-strewn roads at 50 mph. And they crawled through tunnels as trucks with sirens blaring and men dressed as Border Patrol agents pursued them.

"I wouldn't want to go through this in real life," confessed Ávalos, who lost her sandals scrambling down a muddy hill and was forced to run across cactus-dotted fields in socks.

But after three hours, she finished the tour. And Martinez announced triumphantly: "We've crossed the river! We've beaten the Border Patrol!"

Meanwhile, park workers lighted hundreds of lanterns, rewarding visitors with a stunning spectacle.

The community launched EcoAlberto Park seven years ago to give residents an economic alternative to migration. Set at the foot of stunning cliffs, it boasts access to local hot springs, bare-bones camping and boat rides along a bubbling river. The project is funded by local residents — who share ownership — and a grant from the federal government's National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Communities.

Migration has given many residents a way out of poverty.

But migration has also chipped away at the community's traditions, some residents say. Few still wear indigenous garb and many younger residents speak better English than Hñahñu.

"Before, maybe we were poor, but we lived in solidarity with our neighbors," said Martinez, a passionate advocate for preserving the old customs. "Now, every day we become more materialistic."

The idea for leading tourists on mock crossings emerged when several returning migrants were swapping tales of dodging the Border Patrol.

"We're trying to create a source of jobs and make use of our resources," Martinez said. "And hopefully, we'll also create consciousness that being a migrant doesn't mean losing your values."

marionlloyd@gmail.com |

| |

|