|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | September 2006 News Around the Republic of Mexico | September 2006

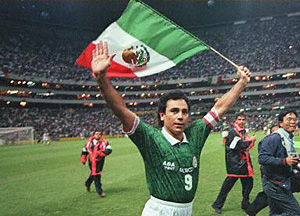

Can Mexican Soccer Reform Itself?

Kenneth Emmond - The Herald Mexico Kenneth Emmond - The Herald Mexico

| | If anything is more prestigious than owning a team that wins games and loses money, it's owning a team that wins both on and off the playing field. |

Despite globalization, examples still abound of Mexican firms whose high returns on investment can be attributed largely to monopoly or near-monopoly markets.

These occur most often in sectors like public utilities and energy or where entry barriers like capital, technology, or intellectual property are high.

Journalists Norma Lezcano and Anibal Santiago have found a sector that consistently loses money despite its monopoly advantages — professional football, or soccer as it's called in English to distinguish it from American football.

Writing in the Aug. 23 issue of Expansión, a Mexican business magazine, they describe the Mexican Football Federation (Femexfut) as "the world's only private monopoly that loses money."

With an estimated 31 million fans from all over Mexico and copious cash flow from ticket sales and spinoff businesses ranging from television rights to sweater sales, one might think it would be impossible to lose money.

However, the authors describe how politics, power, egos, and corruption more than offset what could be a cornucopia of riches.

Reasons for the league's dismal financial status are not hard to find. The most obvious is the fact that many owners of the 18 teams care more about prestige than profit, don't treat their sports ventures as businesses, and write off the losses against other income.

Shady deals between player agents and club officials, obscured by opaque accounting practices, siphon off huge amounts of revenue, and rich teams have open-ended budgets to attract the best players.

Four teams are owned by the national television chains — three by Televisa and one by TV Azteca. These owners get huge profits from advertising sales on televised games whether or not their teams make money.

If anything is more prestigious than owning a team that wins games and loses money, it's owning a team that wins both on and off the playing field. Indeed, the authors quote Justino Compean, president of the Nexcaca team, owned by Televisa, as saying the owners are tired of losing money.

The good news is that other professional leagues do make money and their business plans can be emulated.

One of the best-structured leagues in sports is the 32-team National Football League (NFL) in the United States. With annual revenues of more than $14 billion, it's the most financially successful professional sports league in the world. England's Premier Soccer League has also benefited from major reforms.

Research into NFL operations by no less a financial luminary than Pedro Aspe, Mexico's Finance Secretary during the presidency of Carlos Salinas, yielded a set of 15 concrete recommendations for turning red ink into black.

Together, they would constitute the professionalizing of the league, while putting Mexico in compliance with the standards set by the Federation of the International Football Association (FIFA). That process was supposed to be completed two years ago. The goal now would be to have all the reforms in place by 2010.

One of the most important changes would involve accounting standardization. All teams should have identical corporate structures, with the same accounting rules. The resulting transparency would enable the league to measure results accurately while discouraging many dodgy dealings.

The league itself would also be structured as a company whose shareholders would be the team owners, and it would install a revenue equalization program.

The incorporated league would focus on business administration and be autonomous from Femexfut, whose role would continue to be regulation of the sports activities.

Imposing a salary cap of 50 percent of revenues would encourage teams to develop talent instead of buying it. Combined with revenue sharing, that should make game and season outcomes less predictable — and more exciting for the fans.

The current two-tier system would be scrapped. Now, the poorest-performing teams in a season are demoted to the league's "B" section, while the best-performing "B" teams rise to the "A" section.

Keeping the same 18 teams in a single "Big League" would help all teams achieve long-term contracts with sponsors, providing more revenues and better financial stability for the smaller markets. If the league wanted to expand, it would sell a franchise to the new entrant.

By negotiating collectively with the television chains, the league could lock in more lucrative arrangements, with direct results on the bottom line.

If the league were to adopt these measures, it's believed that it could double annual revenues from today's estimated $3.9 billion dollars to $7.8 billion in five to eight years.

Some teams would clearly benefit more than others, but stability and growing profits for all should provide a powerful incentive as the collective pie grows.

Won't these reform proposals meet stiff owner resistance? Lezcano and Santiago say there are signs that the owners will support them. Aspe presented his conclusions to Emilio Azcárraga, president of Televisa, and Ricardo Salinas Pliego, owner of TV Azteca, before going to the other team owners, and they approved.

Reform would allow the league to do what private monopolies are supposed to do: make money from its exclusive franchise.

Beyond profitability, it would bring the league into line with FIFA rules. Better still, it would substantially enhance Mexico's chances for a successful bid to host the World Cup in 2018.

Kenneth Emmond is a freelance journalist and economist who has lived in Mexico since 1995. Kemmond00@yahoo.com |

| |

|