|

|

|

News Around the Republic of Mexico | October 2006 News Around the Republic of Mexico | October 2006

'Luche Libre' Returning to Its Roots

Melissa Vargas - Star-Telegram Melissa Vargas - Star-Telegram

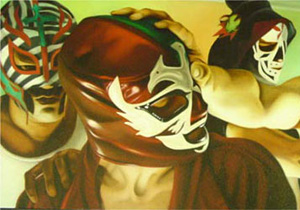

| | Fans cheer the técnicos (good guys) and boo the rudos (bad guys). |

He wears a red and black mask with gleaming crosses embellishing the sides.

His name is Aski — Maya for friend.

Inside a wrestling ring he fights for the good and against the bad.

You’ll never know his name or see his face.

That mystery is part of what attracts fans to Lucha Libre.

The larger-than-life Mexican phenomenon Lucha Libre — loosely translated as free fight — has returned to its roots in Texas. The recent movie Nacho Libre and the children’s cartoon television show ¡Mucha Lucha! have also helped the Mexican masked-wrestler movement move into the mainstream in the U.S.

Much like Hulk Hogan and Vince McMahon have become household names, luchadores like Blue Demón and El Santo are known to many young Hispanic Americans.

Aski, 25, hopes to follow in their footsteps.

“I have always been a wrestling fan,” he said. “When I started I just walked in, and I was a natural.”

With six years of experience under his belt, Aski performs with the Dallas-based Mexican American Wrestling company and makes guest appearances at events in Fort Worth, San Antonio and El Paso. By day he is a law office clerk for a firm in downtown Dallas.

A native of Guanajuato, Mexico, Aski hits the ring most Sundays in the Mexico Lindo Bazaar in Dallas against a backdrop of hair salons, taquerias and music stores.

On a recent Sunday, revelers jumped out of their seats and cheered Aski and his partner, Super Cat, as they took on masked villain Charro Latino and Trebol de Plata — who had lost his mask in a bet.

Fans cheered the técnicos (good guys) and booed the rudos (bad guys) as the four grunted and smacked skin in the ring.

“¡Matalo!” (“Kill him!”), they screamed as they cheered the técnicos on.

No one cared that the wrestlers suited up in a poorly lit, makeshift dressing room or that the ring was set up inside a shabby flea market. No one seemed to mind sitting in folding chairs.

They didn’t come for the atmosphere; they came for the fight

“Lucha Libre has always been el teatro de los pobres, a poor man’s theater,” said Xavier Garza, 37, a Lucha Libre children’s and comic-book author and middle-school teacher in San Antonio. “A person barely able to feed his family can’t take them to the theater, but for a few pesos, you get a show with masks, capes, a protagonist and an antagonist.”

With the rapidly growing Mexican population in the United States, Garza says, it was only a matter of time before Lucha Libre became popular north of the border. After all, the idea started here.

Lucha Libre dates to about the 1930s, when Don Salvador Lutteroth Gonzalez saw an American wrestling match at Liberty Hall in El Paso and decided to take the idea back to Mexico. It was too expensive to bring in American wrestlers, so he cultivated his own — wrestlers who used masks as in the ancient Maya and Aztec warrior tradition, Garza said.

Some of the first home-grown Mexican luchadores include La Maravilla Mascarada, the masked marvel, and El Santo, the saint. They performed for thousands in Mexico City and toured in Spain until circuits started to open up across Mexico.

These days droves of families, from grandparents to infants, gather around blood-spattered rings across Mexico to see wrestlers smack one another over the head with folding chairs and beat one another senseless.

The U.S. and Mexican wrestling styles are similar, save for the masks and acrobatics, Aski said. Because of the technical movements, Mexican wrestlers tend to be smaller than Hulk Hogan-esque American wrestlers. Luchas can also have four to six wrestlers in the ring at once and they fight at a faster pace.

Sergio Reyes, a former Lucha Libre wrestler and co-owner of the nine-year-old Mexican American Wrestling company, also designs masks for luchadores and their fans. He buys the material from Mexico, and his mother sews the masks on a machine in their Dallas home.

As he took a dozen out of a bag recently, Reyes proudly described each one’s intricate details. His eyes danced with excitement as he ran his fingers over a blue and red mask that tied in the back with a shoelace.

“This one is just like Nacho Libre’s,” he said with a chuckle. “This one was made out of a pair of Nike sweat pants,” he said as he pointed to a flap on the back of the yellow mask bearing a stitched “R” — his trademark.

Reyes, 37, who emigrated from Monterrey, Mexico, still wrestles every now and then, but mostly he trains his wrestlers and makes their outfits. When he does get in the ring, he’s the antagonist Mac Reyes — the name under which his father wrestled. Everybody hates a rudo, but Reyes loves the conflict.

“I’m really good at making fun of people,” he said.

People tend to identify with the wrestlers, Garza said. Their characters are designed around real-life issues so people can relate. El Comandante Marcos is a famous masked rebel who fights against an abusive government, and El Perro Aguayo is more of a common man.

Outside the ring, the wrestlers are family, said Reyes’ partner, Lupe Sustaita. The rich culture and deep history that surround the sport have created a strong fraternal bond among the participants, he said.

Some sons are proteges, while others ignored their fathers’ cautions about the sport. Reyes’ father often warned his son about the dangers and refused to watch his son fight. Reyes plans to pass the tradition on to his own sons someday, he said. The sons of masked greats such as El Santo, Gory Guerrero and Ray Mendoza are a few who have continued their fathers’ legacy.

The sport has grown from a mainly underground following in the United States in the late ’90s. Now World Wrestling Entertainment and World Championship Wrestling have even employed luchadores such as Rey Mysterio Jr. and La Parka to attract a Hispanic audience. Aski and Garza hope to nurture the tradition for Americans to enjoy.

“It’s all just part of a movement, and a tradition that is very deeply embedded in Mexican culture,” Garza said.

Lucha Libre

Most Sundays at 6 p.m.

No fee, but donations are appreciated

Mexico Lindo Bazaar

10724 Garland Road, Dallas |

| |

|