|

|

|

News from Around the Americas | December 2006 News from Around the Americas | December 2006

Border Crackdown Fuels Smugglers' Boom

Elliot Spagat - Associated Press Elliot Spagat - Associated Press

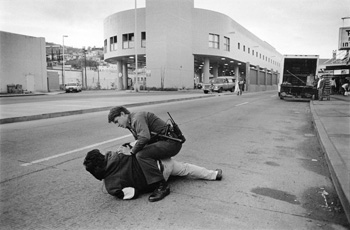

| | Border Patrol agent Sean Monroe takes down a Mexican national in front of the port of entry in Nogales, Arizona. |

A survey conducted by a Mexican government-funded research institution shows that the use of human smugglers to cross the border "has now become a necessity."

Toughened U.S. border enforcement has prompted substantially more illegal immigrants to hire smugglers to help them cross over from Mexico — and competition among sophisticated criminal networks for customers has spawned violence and sometimes death.

The evidence is abundant in border boomtowns, where human traffickers rustle together flocks of immigrants for the journey north. Further evidence comes from tens of thousands of interviews of illegal border crossers in surveys by a Mexican government-funded research institution, which were analyzed by The Associated Press.

"What was once a discretionary expense has now become a necessity," said Jorge Santibanez, who oversaw the surveys while president of Tijuana-based El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

AP's examination of the sweeping data found the use of smugglers on the rise among those surveyed. The interviewees were border crossers who returned to Mexico within three years or were caught and kicked out by the Border Patrol.

About half of those surveyed in 2005 said they had hired a smuggler. That compared to about 1 in 3 in 2004 and just 1 in 6 in 2000.

The actual percentage of illegal immigrants who hire smugglers may be even higher than what the AP analysis found. That's because people may hesitate to admit they hired someone to commit a crime. And the survey excludes those who made it across and remain in the United States — a successful crossing often depends on the expertise of a hired guide.

"You're less likely to get caught if you're using a smuggler," said David Spener, an immigration expert at Trinity University in San Antonio.

While smugglers have spirited people into the United States since Congress first limited immigration in the 1880s, the current spike coincides with heightened border security following the 2001 terrorist attacks.

In this market, where customers pay several times what they did a decade ago, increasingly brazen organizations compete for business.

While most smugglers walk their customers several nights across the deserts that dominate the frontier's nearly 2,000 miles, others take frightening risks.

Inspectors at a San Diego crossing found a 14-year-old girl strapped under the metal bars of a car seat, the driver sitting atop her, and occasionally find children inside compartments that once served as the gas tanks.

Smugglers in Arizona have hijacked loads of customers from rivals — in one case, resulting in a highway shootout that killed four people in 2003. In Tijuana, across from heavily fortified San Diego and the world's busiest border crossing, three bullet-ridden bodies were found in May, covered with roasted chickens. Spanish slang for a smuggler includes "pollero," literally a poultry handler.

"It's become a very good business — more dangerous, but a good business," said Daniel Rivera, 63, who recruits migrants walking the streets of Tijuana.

The Border Patrol has grown from 8,400 agents in 1999 to 12,400 agents today and is projected to reach 18,000 by the end of 2008. President Bush dispatched the National Guard to the border last spring and recently signed legislation to erect 700 miles of fencing from California to Texas. Meanwhile, the government is buying sensors, unmanned aircraft and other border security gadgets.

A senior official at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security said the fact that migrants are increasingly relying on smugglers shows that heightened border enforcement is working.

The trend of hiring smugglers is "a natural outgrowth of the fact that we have more control," said Ralph Basham, commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which oversees the Border Patrol. He expects it will continue.

Critics say the border crackdown isn't working, that the U.S. government's own estimates suggest the number of illegal immigrants here grew by 2 million between 2000 and 2005 to 10.5 million people. The big winners, they say, are the smugglers.

"It has turned a modestly lucrative business into a fantastically profitable industry," said Wayne Cornelius, an immigration expert at the University of California, San Diego.

For this story, the AP analyzed the responses of nearly 61,000 illegal immigrants interviewed by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte researchers over six years, ending in June 2005. The college surveys were conducted at airports, bus stations and crossings in eight Mexican border cities, from Tijuana on the Pacific to Matamoros, just south of Brownsville, Texas.

The study is one of the most ambitious efforts to quantify immigrant smuggling between Mexico and the United States. People surveyed were about evenly split between those deported and those who returned voluntarily after crossing successfully within the previous three years.

Nowhere are smugglers more prominent than Arizona — the border's desolate midsection and the central front in the U.S. government's struggle against illegal crossings.

According to AP's analysis, of those who said they crossed the border through one of three major Arizona corridors, 55 percent hired a smuggler last year. That compared to 28 percent in 2003 and 18 percent in 2000.

Along the entire border the numbers were slightly lower: 47 percent of respondents in 2005 hired a smuggler, up from 20 percent in 2003 and 16 percent in 2000.

For Meliton Aurelio Sanchez, hiring a smuggler became a life-and-death question.

The 42-year-old father of three from Mexico's Veracruz state didn't bother hiring a smuggler in 2001 when he and a friend hiked two days across the border near Naco, Ariz., eventually settling in North Carolina to make $6 an hour as a carpenter.

Sanchez eventually returned home and in May set off again for North Carolina. At the same border he crossed without help before, he paused — spooked by the deaths of hundreds of migrants who perish each year in the desert and convinced that heightened enforcement would force him along obscure routes.

"I'd get lost if I tried alone, left to die in the desert," Sanchez said.

So Sanchez agreed to pay a smuggler $1,500 to get him to Phoenix — like many, he would pay nothing unless he crossed successfully.

Over a two-week span he tried to cross four times in groups of about 20 people, but the Border Patrol nabbed him each time. After being dumped back into Mexico, Sanchez would return to the bustling border boomtown of Altar, a 90-minute drive from the Arizona state line. Mexicans who are arrested are typically freed within 24 hours, after a quick stop at jail for fingerprints. (Sanchez eventually got across. In a later phone interview from Durham, N.C., where he landed a $10-an-hour carpentry job, he said he paid $1,800 to a smuggler to be guided across the Rio Grande near Laredo, Texas, and be shuttled to Chicago by van and bus.)

Like an army in the field, smuggling networks require layers of support. Entrepreneurs have remade Altar, where dozens of boarding houses have sprouted in recent years and shuttle vans line the central square, where migrants gather before they cross. Taco stands share space with a Red Cross trailer that treats migrants for blisters, parasites and swollen fingers.

Francisco Garcia, a former Altar mayor who now runs a migrant shelter, has tallied 14 hotels, 80 boarding houses and 120 taxis — for a community of about 16,000 permanent residents.

"You would think this was a tourist spot but we have nothing — no architecture, no beaches to show off," said Garcia, who describes the town as "the waiting room for migrants."

An estimated 3,500 people pass through every day from January to April, the peak crossing season — before summer, after a home visit for Christmas. Vans line the square, cramming up to 30 people inside and charging the equivalent of $30 a person for a ride to the border.

Tijuana's red-light district offers another glimpse of the increasingly sophisticated smuggling trade.

Before a crackdown in the mid-'90s, illegal immigrants famously massed along an open border and sprinted into the night.

As security increased, smugglers worked solo, collecting $300 tips to guide immigrants on a short walk into San Diego, where the customers would hop a trolley or be collected by a friend or relative. Then came two steel mesh fences, along with more Border Patrol agents, stadium lighting and motion sensors.

Now, the men who worked as solo smugglers a decade ago are minions in a larger scheme. They get paid about $100 to recruit migrants on Tijuana's streets for organizations that charge $1,600 to sneak people through the mountains near Tecate, 35 miles east of San Diego. Some migrants pay $2,500 to hide inside a car trunk.

"Times have changed — it's a lot more difficult to get across, there are a lot more problems, and there's a lot more walking," said Juan Torres, 45, a smuggler who leads immigrants through the mountains. His cut is about $300 from the usual $1,600 fee. Drivers and people who run safehouses in the United States also get a cut.

Migrants linger inside dingy Tijuana hotels, waiting for a cab or bus ride before sunset to begin a trek that can last up to four days. A driver meets them on the U.S. side and speeds them to a drop house, sometimes with deadly consequences as they try to evade Border Patrol highway checkpoints.

One man who survived a July 2005 crash that killed five people — including the man's pregnant wife, 13-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter — said he had agreed to pay $1,500 a person to get his family from Tijuana to Los Angeles.

Business is so good that some Border Patrol agents are taking a cut. In one of several recent convictions, two supervisory agents in southeastern California admitted taking nearly $180,000 in bribes to release immigrant smugglers and illegal immigrants from federal custody.

Smugglers — often called "coyotes" — have flourished for decades and witnessed boom times before. Demand grew after a temporary worker program with Mexico ended in 1965 and again after the 1990s crackdown in San Diego and El Paso, Texas.

Smuggling entered a new growth phase after 2000 as the Border Patrol shifted agents to Arizona. The Border Patrol's Arizona stations accounted for half of the agency's 1.2 million arrests along the Mexican border in 2005, up from only 8 percent of 1.2 million arrests in 1992.

U.S. officials say they make no systematic effort to track how many of the people they arrest hired smugglers. Customs and Border Protection has not responded to a Freedom of Information Act that the AP submitted in April to disclose what information it collects in the Border Patrol's database of apprehensions.

Bulmaro Arizmendez del Carpio, 22, was one of those caught by the Border Patrol. He decided to save the $1,600 fee and forsake a guide, then walked three days in triple-digit temperatures in early June before being arrested with 17 others outside Phoenix. After the first day he ran out of water and twice had to fill jugs with dirty water from cow tanks. His feet were covered with blisters.

Back at a bus station in Mexico, where he was deported, Arizmendez said, "If we had hired a smuggler it would have been different."

Associated Press researcher John Parsons contributed to this report. |

| |

|