Seattle to Remove Automated Toilets

Stuart Isett - The New York Times Stuart Isett - The New York Times

go to original

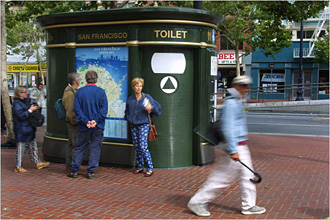

| | One of San Francisco’s toilets, which, officials say, always need maintenance adjustments. (Peter DaSilva/The New York Times) | | |

Seattle — After spending $5 million on its five automated public toilets, Seattle is calling it quits.

In the end, the restrooms, installed in early 2004, had become so filthy, so overrun with drug abusers and prostitutes, that although use was free of charge, even some of the city’s most destitute people refused to step inside them.

The units were put up for sale Wednesday afternoon on eBay, with a starting bid set by the city at $89,000 apiece.

The dismal outcome coincides with plans by New York, Los Angeles and Boston, among other cities, to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars for expansion this fall in their installation of automated toilets — stand-alone structures with metal doors that open at the press of a button and stay closed for up to 20 minutes. The units clean themselves after each use, disinfecting the seats and power-washing the floors.

Seattle officials say the project here failed because the toilets, which are to close on Aug. 1, were placed in neighborhoods that already had many drug users and transients. Then there was the matter of cost: $1 million apiece over five years, which because of a local ordinance had to be borne entirely by taxpayers instead of advertisers.

In the typical arrangement involving cities that want to try automated toilets, an outdoor advertising company like JCDecaux provides, operates and maintains them for the municipality in exchange for a right to place ads on public property like bus stops and kiosks. Revenue from the advertisers flows to both the company and the city.

But a strict advertising law here barred officials from such an arrangement, meaning Seattle had to pick up the entire $5 million cost. “That’s a lot of money, a whole lot,” said Ray Hoffman, director of corporate policy for Seattle Public Utilities, the municipal water and sewage agency that ran the project.

Richard McIver, a Seattle city councilman, agrees. “Other cities around the world seem to be able to handle toilets civilly,” Mr. McIver said. “But we were unable to control the street population, and without the benefit of advertising, our costs were awfully high.”

Automated toilets have been common fixtures on European sidewalks for decades. But they have been less popular in American cities, where concerns including their appearance, cleanliness and tendency to attract illegal activity have slowed their installation.

In Seattle, problems arose almost immediately. Users left so much trash behind that the automated floor scrubbers had to be disabled, and prostitutes and drug users found privacy behind the toilets’ locked doors.

“I’m not going to lie: I used to smoke crack in there,” said one homeless woman, Veronyka Cordner, nodding toward the toilet behind Pike Place Market. “But I won’t even go inside that thing now. It’s disgusting.”

In May, the City Council decided to close the toilets. It agreed to pay an additional $540,000 fee to end, five years early, its maintenance contract with the operator, Northwest Cascade, a local company with no prior experience in the field that was chosen when established operators like JCDecaux and Cemusa declined to bid because the project lacked advertising revenue.

Seattle’s automated toilets, 12 feet in circumference and 9 feet high, are round and shiny like steel cans. New York’s design is a modernist box of steel and frosted glass, while the toilets in Los Angeles and San Francisco resemble ornate trolley cars without wheels. All have mechanisms that control the doors and clean the floors.

Nowhere was the controversy over public toilets more bitter or longer than in New York, where it lasted 18 years and vexed three mayoral administrations.

“At this point, I’m glad it’s happening at all,” said Fran Reiter, a deputy mayor in the Giuliani administration who led a failed effort to build toilets in the city in the mid-1990s.

In 2005, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg signed an agreement giving Cemusa, a Spanish company, a 20-year franchise to sell advertisements on bus stops, newsstands and kiosks. In return, the city will receive $1.4 billion in cash and 20 automated toilets. The first, in Madison Square Park, opened in January. Four more are to be installed in Brooklyn and Queens this fall.

In Boston, a similar advertising contract has paid for six automated toilets, said Dot Joyce, a spokeswoman for Mayor Thomas M. Menino, and the city plans two more this fall.

“It works very well for us,” Ms. Joyce said.

But opposition to advertising is hampering the effort in Los Angeles. In 2002, the city gave CBS Outdoor and JCDecaux a contract to sell advertisements on bus shelters, kiosks and newsstands in exchange for 150 automated toilets. Thirteen are operational so far, with two more coming this fall, said Lance Oishi, who leads the project for the city. Six of the units are downtown near Skid Row, but others sit near transit stations or shopping areas, Mr. Oishi said, and, contrary to Seattle’s experience, all 13 have remained clean and largely crime free.

Neighborhood groups are blocking construction of new structures on which to place advertising, however, and that means there is not enough revenue to support additional toilets, Mr. Oishi said.

“I do feel some frustration that things are not moving as fast as I’d like,” he said.

Some cities have had problems with maintenance. The 25 automated toilets in San Francisco require constant fiddling, officials there say. “You need a dedicated crew taking care of them every day,” said J. François Nion, executive vice president of JCDecaux North America, whose French parent company maintains 3,229 automated toilets worldwide.

Rather than automated toilets, some cities are looking for cheaper alternatives that would be cleaned by human attendants. One prototype, to be installed next month in Portland, Ore., would cost $50,000 each, compared with some $300,000 for an automated unit.

Randy Leonard, a Portland city commissioner, helped design that toilet, which in addition has open gaps at the top and bottom of the door, a feature discouraging drug abuse, prostitution and the like.

But given that lesser privacy, it is unclear how popular such a toilet might be, as Mr. Leonard acknowledges.

“We in the U.S. have yet to shed our puritanical roots,” he said. “We are uptight about toilets.” |