|  |  |  News Around the Republic of Mexico | November 2008 News Around the Republic of Mexico | November 2008

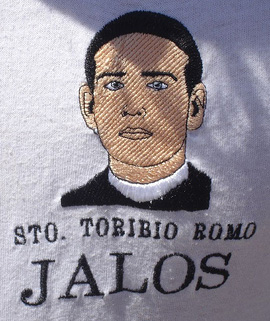

Martyred Priest Becomes Unofficial Patron Saint of Migrants

Oscar Avila - Miami Herald Oscar Avila - Miami Herald

go to original

| | Mexicans put his face on T-shirts and write ballads about how he guides migrants through the desert. | | |

Three years ago, José Guadalupe Ortega crossed illegally into Texas through a hand-dug tunnel with men he didn't know or trust.

If things went bad, he knew he couldn't count on getting last rites.

So before setting off, Ortega said his goodbyes and came to this central Mexican village to confess his sins and seek protection from the immigrant's unofficial patron saint.

Each week, worshipers also come to ask St. Toribio Romo to cure terminal illnesses and save them from financial ruin. But as the U.S. government builds walls and boosts patrols on the border, immigrants see a successful journey as no less a miracle.

Now planning a return trip to Atlanta, where he painted houses with his son, Ortega has joined the throng to ask Toribio once again for safe passage.

"You go with faith, in God and in Father Toribio," said Ortega, 53. "All we can do is pray. We don't know when we will come back or if we will come back."

Romo's importance to immigrants has turned him from an obscure martyred priest into a political symbol and cultural icon. Mexicans put his face on T-shirts and write ballads about how he guides migrants through the desert.

Each Sunday, Santa Ana's population of 250 grows tenfold as Mexicans make the first stop on a journey to points north. The buses filling the parking lots display the hometowns of many immigrants to Illinois.

The most devout Roman Catholics already knew Toribio Romo as one of countless priests killed in the 1920s during the Cristero War waged by the government against the church.

Scholars trace his new prominence to a widely told tale from the 1990s when three men from Michoacan state were dying in the Arizona desert until a man came to lead them to a fountain. "My name is Romo and I live in Santa Ana de Guadalupe," the man reportedly told them.

When Pope John Paul II canonized Romo with other martyrs of the Cristero War in 2000, his stature was secured.

Now dozens of buses navigate stalls that sell Toribio T-shirts, caps and figurines in addition to the usual Mexican small-town display of quesadillas and pirated DVDs.

Visitors can even buy a CD that recounts the glories of Romo through songs such as "Miracle in the Rio Bravo," as Mexicans call the Rio Grande.

By late morning, a crush of pilgrims is scaling the steps toward a chapel that houses the saint's remains, vials of blood and scraps of clothing from the day he died.

Other visitors line up to confess their sins while families peek inside a replica of Romo's home inside an earthen building that evokes a Disney display.

The Rev. Gabriel González watches this hoopla with mixed emotions. He knows Romo has become a cottage industry but insists much of the commerce - taco stands, straw hats - is geared to accommodating the crush of pilgrims.

González says he makes no apologies for the sanctuary's skillful marketing of the saint.

"There might be some things that we need to correct so that people don't try to take advantage and make money," he said. "But we also need to correct people who want to criticize us. If people come here with faith in their hearts, we are satisfied."

Outside the sanctuary, a seminarian stands by a tabletop model of an expanded church going up in the distance. He is soliciting donations for the new facility, which will accommodate about 1,000 seated worshipers, about five times the current capacity.

The best sales pitches, however, are the testimonials of visitors such as Mario Alvarez, a sales representative from Guadalajara. Alvarez's brother, like many, made a nightmarish crossing into the U.S. through the Arizona desert.

When his brother returned to the family home, he spotted a picture of Romo on the wall. Alvarez said his brother remarked: "Hey, I know that guy. He crossed with us."

"I believe him," Alvarez said after recounting the tale. "Imagine that he would lie to my mother about something like that."

The prospective immigrants know these days, they need Romo more than ever.

Drug traffickers are preying on the routes used to smuggle migrants through Mexico. At the border, the U.S. government aims to complete about 670 miles of fencing this year. And many of the Mexicans who do make it to the U.S. are returning home because of a lack of jobs.

Jacqueline Hagan, whose upcoming book "Migration Miracle" features St. Toribio, said those considering migration are more likely to pray or consult with their ministers than seek advice from their families before making the journey.

"It's such a risky decision with the uncertainty of making the trip, the fear of dying on the trip and never seeing your family again," said Hagan, a sociology professor at the University of North Carolina. "The only way they can make meaning of this trip, the only way it makes any sense, is through God."

Everardo Delgado said he has heard of a man from his small town who was bitten by a scorpion while migrating through the desert. In that desperate hour, Delgado said, the man prayed to Romo and came out unharmed.

Delgado, a retired factory worker, had recently come to Santa Ana for a simpler request. He prayed that his daughter's yearlong wait for a U.S. visa would finally end.

Soon after, the family got word that her visa came through.

"I really believe it was a miracle," said Delgado, 66.

That sort of faith is on display in a room down a walkway from the chapel.

Some believers have hung sonograms of the healthy babies that Romo delivered. Others show photos of the scars caused by the car accident that Romo helped them survive.

And then there are the smiling family photos of relatives reunited in the U.S. One reads: "Thank you, St. Toribio, for letting me cross the border to be at my son's side."

One way or another, they all credit Toribio for giving them a new life. |

|

|  |