|  |  |  News Around the Republic of Mexico | November 2009 News Around the Republic of Mexico | November 2009

Political Games

Bill Littlefield - Boston Globe Bill Littlefield - Boston Globe

go to original

November 02, 2009

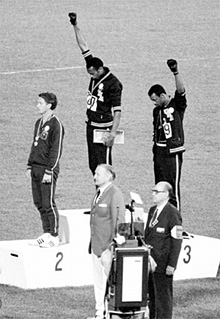

| | From bloody riots that proceeded it to raised fists and other protests, the 1968 event forever changed the Olympics. |  |

If the world’s press had been more attentive to events in Mexico City in the early fall of 1968, and if the Mexican government had not been so successful in covering up its army’s murderous response to one particular student demonstration, the 1968 Olympics might never have occurred.

On Oct. 2 of that year, as workers struggled to complete preparations for the Games, about 5,000 students staged a peaceful, antigovernment demonstration at the Plaza de Las Tres Culturas, about 15 miles from the Olympic Village. Apparently on the orders of President Diaz Ordaz, helicopters swooped down on the plaza; soldiers sealed off exit routes with tanks; and snipers opened fire from the surrounding buildings on the unarmed demonstrators.

As Richard Hoffer writes, "The haze of history would be slow to lift on this one." Initial reports in the Mexican press claimed the students had fired first, "killing a general and wounding eleven soldiers," and that the army "had killed twenty civilians," essentially in self-defense.

"In fact," as Hoffer writes, "according to accounts that would unfold over the years, as documents would continue to be declassified . . . it was an outright massacre." The death toll among the demonstrators "may have been as high as 325, thousands more disappearing into prisons, some of them for years."

Avery Brundage, head of the International Olympic Committee, did his part to maintain the illusion that there was no reason to see Mexico City as anything but a happy host for the games. In response to the first stories of the slaughter, Brundage reported that he’d been at the ballet with friends in Mexico City that night, "and we heard nothing of the riots."

If the truth about the non-riot had come out in the days following the murders in the Plaza de Las Tres Culturas, would US athletes have proceeded to Mexico City? Richard Hoffer thinks not. "We wouldn’t have sent our kids down there," he said recently in an interview.

But the Games began on schedule. And shortly thereafter, the event attracted the attention of the world when Tommie Smith and John Carlos, having finished first and third in the 200-meter run, stood on the podium and lifted black-gloved fists over their bowed heads. Their images went out on live television. Nobody could say the protest hadn’t happened.

That protest came as a result of a failed movement among US athletes to boycott the Games, not because of repression in Mexico, but because of the long history of oppression of blacks in America. Many of the runners’ teammates, black and white, backed them, and that support grew when the Olympic lords to whom Hoffer refers as "the old white men" removed Smith and Carlos from the team and hustled them out of Mexico.

One of the important achievements of "Something in the Air" is Hoffer’s recounting of the other rebellious - albeit sometimes quietly rebellious - acts that characterized the ’68 Games and began to change the way at least some of the athletes thought about themselves and the authority figures to whom they felt allegiance.

The protests weren’t limited to US athletes. When Czech gymnast Vera Caslavska stood on the podium listening to the anthem of the Soviet Union, she lowered her head. ABC’s Jim McKay told his television audience that "this does not appear to be an accident." No, probably not, since two months earlier, Russian tanks had rumbled through Prague, and Caslavska had been one of the signers of " ‘the Manifesto of 2000 Words’ protesting Soviet occupation." Having fled Prague, Caslavska prepared for the ’68 Games by running in a field and swinging on tree limbs. As Hoffer writes, her gesture was "as remarkable as a fist in the sky," and at least as courageous.

Given the political ramifications and consequences of the Mexico Olympics, it’s significant that in "Something in the Air," Hoffer has also written powerfully about athletic achievements there. These were the games during which Dick Fosbury, having trained on beer in a Volkswagen bus, turned the art of high-jumping upside down by showing the world how well he could go over the bar head first. This also was the arena in which Bob Beamon so thoroughly obliterated the long-jump record that one of his competitors said after Beamon’s record-setting leap: "We can’t go on. . . . We’ll look silly." Another moaned, "Compared to this jump, we are as children."

But of course the lasting image of the Games remains Smith and Carlos, and the most important achievement of this reconsideration of Mexico ’68 is to remind readers that they did not act in a vacuum or without cause. To that end, Hoffer includes the story of Mel Pender, a champion sprinter and US Army captain who served in Vietnam. Pender, a victim of discrimination all his life, was told by a colonel representing the US military in Mexico City that if he demonstrated at the Games, "you could really ruin your career. You could be court-martialed, you could even go to Fort Leavenworth." He was also advised that if he behaved himself, his application for flight school in the States would be approved. As a result, when Pender made the podium, he stood quietly and accepted his medal, though he wished he could have supported his banished teammates. As Hoffer reports, Pender stood silently "on pain of a Vietnam assignment . . . hating himself for it."

When the Games ended, Pender was sent back to Vietnam.

Bill Littlefield hosts National Public Radio’s "Only a Game." His most recent book is also titled "Only a Game."

|

|

|  |