|  |  |  Americas & Beyond Americas & Beyond

The Army: Be All That You Can’t Know

Christine Armario & Dorie Turner - Associated Press Christine Armario & Dorie Turner - Associated Press

go to original

December 22, 2010

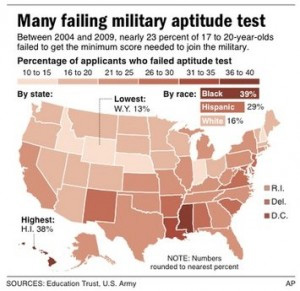

| | U.S. map shows percentage of failed aptitude tests in each state by applicants between the ages of 17 and 20 between 2004 and 2009, and percent of failed tests nationally by race during same period. |  |

Nearly one-fourth of the students who try to join the U.S. Army fail its entrance exam, painting a grim picture of an education system that produces graduates who can’t answer basic math, science and reading questions, according to a new study released this week.

The report by The Education Trust bolsters a growing worry among military and education leaders that the pool of young people qualified for military service will grow too small.

“Too many of our high school students are not graduating ready to begin college or a career — and many are not eligible to serve in our armed forces,” U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan told the AP. “I am deeply troubled by the national security burden created by America‘s underperforming education system.”

The effect of the low eligibility rate might not be noticeable now — the Department of Defense says it is meeting its recruitment goals — but that could change as the economy improves, said retired Navy Rear Admiral Jamie Barnett.

“If you can’t get the people that you need, there’s a potential for a decline in your readiness,” said Barnett, who is part of the group Mission: Readiness, a coalition of retired military leaders working to bring awareness to the high ineligibility rates.

The report by The Education Trust found that 23 percent of recent high school graduates don’t get the minimum score needed on the enlistment test to join any branch of the military. Questions are often basic, such as: “If 2 plus x equals 4, what is the value of x?”

The military exam results are also worrisome because the test is given to a limited pool of people: Pentagon data shows that 75 percent of those aged 17 to 24 don’t even qualify to take the test because they are physically unfit, have a criminal record or didn’t graduate high school.

Educators expressed dismay that so many high school graduates are unable to pass a test of basic skills.

“It’s surprising and shocking that we are still having students who are walking across the stage who really don’t deserve to be and haven’t earned that right,” said Tim Callahan with the Professional Association of Georgia Educators, a group that represents more than 80,000 educators.

Kenneth Jackson, 19, of Miami, enlisted in the Army after graduating from high school. He said passing the entrance exam is easy for those who paid attention in school, but blamed the education system for why more recruits aren’t able to pass the test.

“The classes need to be tougher because people aren’t learning enough,” Jackson said.

This is the first time that the U.S. Army has released this test data publicly, said Amy Wilkins of The Education Trust, a Washington, D.C.-based children’s advocacy group. The study examined the scores of nearly 350,000 high school graduates, ages 17 to 20, who took the ASVAB exam between 2004 and 2009. About half of the applicants went on to join the Army.

Recruits must score at least a 31 out of 99 on the first stage of the three-hour test to get into the Army. The Marines, Air Force, Navy and Coast Guard recruits need higher scores.

Further tests determine what kind of job the recruit can do with questions on mechanical maintenance, accounting, word comprehension, mathematics and science.

The study shows wide disparities in scores among white and minority students, similar to racial gaps on other standardized tests. Nearly 40 percent of black students and 30 percent of Hispanics don’t pass, compared with 16 percent of whites. The average score for blacks is 38 and for Hispanics is 44, compared to whites’ average score of 55.

Even those passing muster on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, or ASVAB, usually aren’t getting scores high enough to snag the best jobs.

“A lot of times, schools have failed to step up and challenge these young people, thinking it didn’t really matter — they’ll straighten up when they get into the military,” said Kati Haycock, president of the Education Trust. “The military doesn’t think that way.”

Entrance exams for the U.S. military date to World War I. The test has changed over time as computers and technology became more prevalent, and skills like ability to translate Morse code have fallen by the wayside.

The test was overhauled in 2004, and the study only covers scores from 2004 through 2009. The Education Trust didn’t request examine earlier data to avoid a comparison between two versions of the test, said Christina Theokas, the author of the study. The Army did not immediately respond to requests for further information.

Tom Loveless, an education expert at the Brookings Institution think tank, said the results echo those on other tests. In 2009, 26 percent of seniors performed below the ‘basic’ reading level on the National Assessment of Education Progress.

Other tests, like the SAT, look at students who are going to college.

“A lot of people make the charge that in this era of accountability and standardized testing, that we’ve put too much emphasis on basic skills,” Loveless said. “This study really refutes that. We have a lot of kids that graduate from high school who have not mastered basic skills.”

The study also found disparities across states, with Wyoming having the lowest ineligibility rate, at 13 percent, and Hawaii having the highest, at 38.3 percent.

Retired military leaders say the report’s findings are cause for concern.

“The military is a lot more high-tech than in the past,” said retired Air Force Lt. Gen. Norman R. Seip. “I don’t care if you’re a soldier Marine carrying a backpack or someone sitting in a research laboratory, the things we expect out of our military members requires a very, very well educated force.”

A Department of Defense report notes the military must recruit about 15 percent of youth, but only one-third are eligible. More high school graduates are going to college than in earlier decades, and about one-fourth are obese, making them medically ineligible.

In 1980, by comparison, just 5 percent of youth were obese.

|

|

|  |