Holiday shopping still beckons, even with the ancient Maya supposedly forecasting the end of the world for 2012.

Reluctant shoppers may hate the news, but the long-awaited, much-hyped, and entirely farcical Maya apocalypse is just that — and archaeologists can't wait until it passes so they don't have to explain anymore why it was never going to happen.

"I would suggest to people that they not sell their house, quit their job, nor say something nasty to someone they think they will never see again," University of Illinois archaeologist Lisa Lucero says. Her students still need to do their homework, she adds.

On December 21, 2012 - or thereabouts - the ancient Maya calendar rolls over to start a new 394-year century, or baktun. And that's pretty much it, despite all efforts by writers and filmmakers to market the notion that the Maya predicted the crack-up of Earth.

Born from a misinterpretation of an inscription found at a now-pulverized Maya site in Mexico's Tabasco region, the end-of-the-world talk reached its highest point with the 2009 disaster thriller "2012," starring John Cusack.

Theories about how the world would meet its end have ranged from the appearance of a rogue planet called Nibiru that would sideswipe Earth, to a European physics experiment spawning a world-gobbling black hole.

|

"People tend to worry about the wrong things," says MIT physicist Max Tegmark, who studies the possible real end of the universe tens of billions of years from now. "I don't spend a lot of time worrying about anything particular to this year," he adds. Rather than ancient prophecies, Tegmark says what worries him is computer intelligence getting out of control in the coming decades.

The idea of the 2012 apocalypse springs from stone inscriptions now housed at the Carlos Pellicer Cámara Regional Anthropology Museum in the Mexican city of Villahermosa.

Discovered in the now-destroyed ruin called Tortuguero, the inscriptions were part of the dedication of a tomb or shrine at the site carved around the 7th century A.D., according to Maya scholar David Stuart of the University of Texas, author of "The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth About 2012."

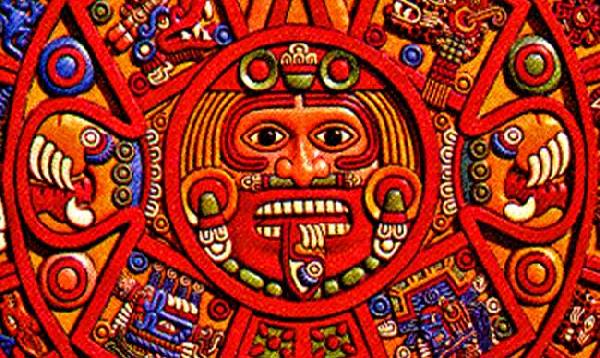

The inscription mentions the appearance of a Maya deity, Bolon Yokte' K'uh, on the date 13.0.0.0.0 in the Maya "long count" calendar. That corresponds to December 21, 2012 - or the 23rd in an analysis presented at the University of Pennsylvania's Penn Museum this year - a turning over of the ancient calendar that occurs roughly every 5,125 years.

The success of the 2006 book, 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl by Daniel Pinchebeck, re-popularized the idea of December 21st representing a big deal to the Maya, tying it to the Tortuguero inscription and spawning a series of increasingly apocalyptic imitators. But archaeologists say that the ancient Maya weren't interested in predicting apocalypse — they couldn't even foresee their own society's collapse.

The ancient Maya built monumental centers at least as early as 900 B.C., sprinkling pyramid-centered cities throughout Central America. It was a way of life that largely collapsed around 850 A.D., except in Mexico's Yucatan. The cities were ruled by kings, who often took on the persona of gods or paraded their effigies in rituals marking their rule, typically imploring the gods for rainfall and a successful harvest. Those rulers left behind inscriptions linking their dynasties to ancient ancestors and deities, Stuart says.

"The ancient Maya did not see the world in terms of endings, but rather in terms of constant renewal," Stuart says. Classic Maya mythology revolved around history repeating in endless cycles corresponding to trillions of years of time, according to Maya experts, including Simon Martin of the University of Pennsylvania.

A doomsday prophecy was the last thing likely to be uttered by these ancient dynasty-builders. What's more, Stuart was part of a team led by archaeologist William Saturno of Boston University that reported in May from the Guatemalan ruins of Xultun the discovery of a scribe's hut painted with calendar markings.

The markings tracked Venus, Mars, and dates corresponding to a time after the year 3500, the team reported in the journal Science. That shows the Maya obviously expected the world to continue for many centuries. "So much for the supposed end of the world," Saturno said.

Today, more than 6 million Maya live in Central America. The ancient kings vanished but the people remained.

And if 2012 doesn't bring the end of the world, "I do know it is helping tourism" in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, Lucero says.