Finance Minister Luis Videgaray went on a Tuesday morning radio show hosted by one of the leading government critics and stressed that the Mexican government won't be privatizing state-run oil monopoly Petroleos Mexicanos or the oil reserves themselves.

"We are not selling off the oil rent," he told radio host Carmen Aristegui, echoing a similar phrase used on national television late Monday by President Enrique Peña Nieto.

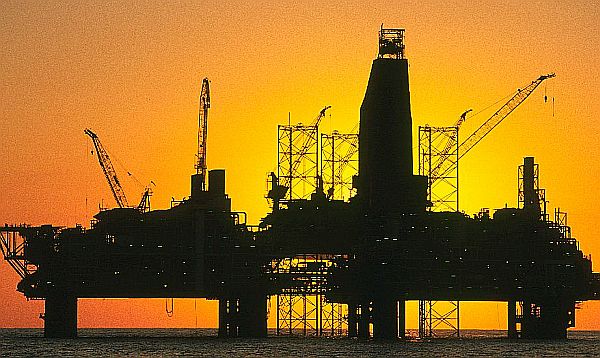

Mexico was the first big oil producer to nationalize its industry in 1938. The proposal unveiled on Monday seeks to amend the Constitution to allow for profit-sharing contracts between the government and private companies. At the moment, state giant Pemex is the only player allowed to exploit oil and gas and can enter into service contracts only with private firms, where companies are paid a fee for certain tasks. The trouble is, Mexico's oil output has fallen sharply in the past decade as Pemex struggles to take on more complicated and costly fields in places such as the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The proposal, which is expected to win congressional approval, has already been called "treason" by nationalistic politicians including former presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who narrowly lost the 2006 election and led months of street protests. Mr. López Obrador is planning on street protests against the bill in early September, when it is due to be taken up by congress.

|

| For decades, Mexicans have been taught that the oil nationalization was the country's biggest achievement, redeeming a history of defeats |

Another leading figure on the left, former presidential candidate Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, said only hours after the proposal that he would do everything he could to block the bill. Mr. Cárdenas is the son of Lázaro Cardenas, the Mexican president who expropriated the industry.

For decades, Mexicans have been taught that the oil nationalization was the country's biggest achievement, redeeming a history of defeats that include the 1848 US-Mexico war, in which the country lost more than half its territory. Polls show a majority of Mexicans are wary of private investment in the oil industry.

"This process is the end of the last bastion of Mexican nationalism, if we think of Pemex as nationalism made into a company," said Lorenzo Meyer, a historian at the UNAM, Mexico's largest public university. "Pemex is the flagship of Mexican nationalism, and when it's gone, what's left? What can a Mexican feel a little bit proud of? Mexico has nothing else to feel proud about. The economy is a pile of junk, the justice system is a pile of junk, and the educational system is awful. What's left?"

On Tuesday, top officials tried to reassure ordinary Mexicans that the country's oil wealth wasn't being handed over to rapacious foreign interests. Finance Minister Mr. Videgaray took to the airwaves, as did Energy Minister Pedro Joaquín Coldwell, and Foreign Minister José Antonio Meade, who held the energy position in the past administration.

Mr. Videgaray said the government rejected the model of granting concessions to private firms as giving up too much of Mexico's control over oil, and opted for profit-sharing as a way for Mexico to reverse a steep decline in oil production without taking on vast amounts of debt. He noted that Pemex's annual investments have soared to $20 billion a year from around $3 billion a decade ago, while crude oil and natural gas production have fallen.

Mr. Videgaray said contracts would be "progressive," meaning that if an oil company were to hit a huge strike, the Mexican government would get a greater percentage of the overall profits generated by the field.

Videgaray said the share of profits going to oil companies would be less than 50 percent, but depended on the type of field. He said private firms would be taking on the downside risks such as hitting a dry hole or a fall in oil prices. At the moment, Pemex bears all the risk with service contracts.