Mexico City, Mexico — On the way home from a pre-Christmas fiesta, Mauricio Rodriguez, after "two tequilas," felt clear-headed and focused, "not dizzy or anything."

So when the IT help desk employee failed one of Mexico City’s feared alcoholímetros — those pervasive breath tests at holiday checkpoints — he knew he would be saying goodbye for a while. No ticket. No warning. "Come get my wife," he told his father by phone before being whisked off in a squad car. "They’re taking me away."

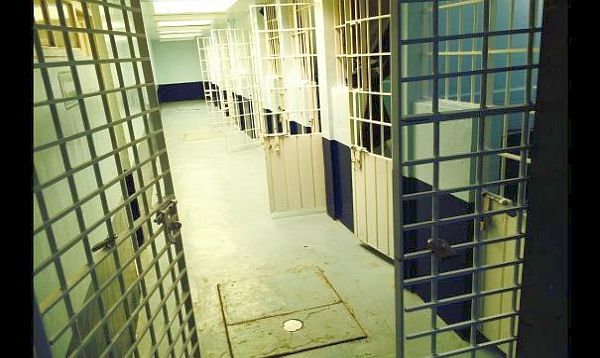

Rich or poor. Legislator or bricklayer. Foreign or domestic. Anyone in Mexico’s capital city who exceeds the legal 0.08 alcohol limit must take a strange little journey to a squat brick building next to a playground on the west side of town where they can sit, and sit, and sit and think about what they’ve done. Part prison, part timeout for adults, the official name is the Center for Administrative Sanctions and Social Integration. But everybody knows it as "El Torito."

"It’s like jail-lite. Mild jail," Jorge Emilio González Martínez, a senator with Mexico’s Green Party, told reporters after he spent his drunken-driving penance there earlier this year. "They make you conscious of your error. I have learned."

|

| At El Torito inmates must attend classes to learn about the dangers of drug and alcohol abuse |

Winter holidays are Torito’s boom time. In Mexico, the whole month of December seems devoted to one bacchanal or another. Celebrations for the Virgin of Guadalupe blend into nightly pre-Christmas posadas and boozy company lunches that bubble over into New Year’s celebrations. Christmas bonuses, required by the government, flesh out the national wallet.

"The end of the year we see an exceeding amount of people arriving," said Torito’s director, Rosa Maria Laguardia. "Very powerful people. Humble people. Engineers, lawyers, artists, journalists. Everyone. Everyone ends up here."

The place is not without its charm. One recent day during the holiday rush, several inmates, including one wearing a Corona T-shirt, played a spirited game of volleyball in the courtyard. A refreshment stand nearby served sodas and chips. There’s a library, movies, and a small glass shrine to the Virgin Mary decorated with flowers. Christmas Eve warranted a special menu: turkey in plum sauce and spaghetti soup.

"Prison I’m sure is worse," Rodriguez said.

A former slaughterhouse, Torito has been drying out drinkers since the late 1950s, but only in the past decade, since the introduction of the city’s breath-testing program, has it taken on such cultural import. More than 100,000 people have slept it off within its white-washed brick cells in those 10 years, spending up to a day and a half before walking free. Other civil infractions can land you in Torito — drinking on the street, disturbing the peace, scalping tickets, cleaning windshields at stoplights, getting rowdy at soccer games — but the majority are drivers stopped by the breath-test cops.

"The objective of the institution is to make people aware of the damage they can cause themselves and others" by drinking and driving, Laguardia said. "They can suffer tremendous crashes, and often people die."

About 1,500 people pass through Torito during an average month. December surpassed that figure in its first three weeks, around the time city authorities announced their holiday special: Breath analyzers would be going 24 hours a day until early January in twenty fixed and roving locations.

|

| Inmates play volleyball in the courtyard at El Torito |

The Internet fought back, with Facebook and Twitter users calling out checkpoint locations. Easy Taxi, an Uber-esque mobile app, sent out an e-mail to its users on December 17th warning about the round-the-clock alcoholímetros.

"If you want to avoid falling into Torito, it’s better to download Easy Taxi for free," the company wrote.

Rodriguez was worried when he saw Torito’s sign in the wee hours Saturday — "Don’t be surprised, the alcoholimetro program violates no fundamental rights." He entered through the white metal doors and stepped onto the cold stone floor.

"I asked one of the guards here, ‘Hey, what do I do? What’s the dynamic? I don’t want to get stabbed.’ He’s like, ‘No, everybody just wants to leave.’"

Unfortunately, you can’t. Depending on the severity of the infraction, inmates must spend 20 to 36 hours at Torito. While fixers hover outside to arrange a type of bail for some, even the wealthy and well-connected have to return to complete their hours. The prisoners sleep on concrete bunks and the cells have metal bars, but they’re not locked and the guards don’t carry guns.

By 6:30 am, the prisoners are roused for breakfast, no matter the hangover. There are medical checks, discussions with psychologists, and classes to learn about the dangers of drugs and alcohol.

Outside, family members wait nervously for their kin to be released. A paparazzo in a leather jacket pulled up on a motorcycle, his lens trained on the door, hoping to get lucky with a celebrity sighting. Antonio Guerrero, a thin 22-year-old who works at a parking garage, stepped onto the sidewalk rubbing his eyes after logging his 36 hours. "Not very pleasant in there," he said.

He got nabbed while walking on the street after "three drinks." He said he paid the cop $100 pesos — about $8 — and even so he was spirited away to Torito. "It’s because it’s Christmas. The police want to pick up as many people as possible to get their little gifts."

Rodriguez came out in a better mood. "Freedom!" he yelled and raised both fists in the air. He hugged his wife and daughter. "Right now I’m going to go for some cold beers," he said. "I’m not going to drive, though."

Original Story