|

|

|

Health & Beauty | On Addiction | January 2005 Health & Beauty | On Addiction | January 2005

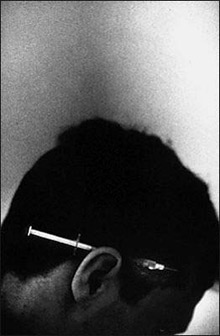

The Pen Is Mightier Than The Needle

Seth Mnookin - Slade Seth Mnookin - Slade

Before Seth Mnookin was a feature writer for 'The New Yorker' and 'Newsweek', he was an intravenous heroin addict. Here, he recounts how journalism gave him a 'bridge to normal living.' Before Seth Mnookin was a feature writer for 'The New Yorker' and 'Newsweek', he was an intravenous heroin addict. Here, he recounts how journalism gave him a 'bridge to normal living.'

I was flying south on an assignment, I told the kindly looking middle-aged woman sitting next to me. I worked for magazines, I said. "You know, the life of a writer. It's a bitch. I spend more hours than I can count in airport lounges and Holiday Inns. It's kind of lonely, but that's reality."

That was in October 1997. I was 25 and had spent the years since graduating focusing all of my desperate energy on my career as an intravenous drug addict. I was 6ft tall and weighed less than 150lb. That entire year, I earned $3,192 in legal income as a waiter and shop assistant. I hadn't done any real writing in years. The previous summer, Details had shipped me off to Mexico for an experimental, two-day detox that was supposed to miraculously cure my heroin addiction, but that failed spectacularly. Now I was on my way to Delray Beach, Florida, with a bag of clothes, books and an admission ticket to a long-term treatment centre.

It had been three years since I first tried snorting heroin. I was living in New York City, and within weeks I was using every day. It had been two years since I had moved back to Boston, ran out of money, and began shooting up. Now, after a dozen hospitalisations and overdoses, more than $10,000 in credit-card cash advances, and thousands of dollars stolen from friends, lovers and family, I was cashing in my last chip. My parents agreed to front the money for the Renaissance Institute, a hard-core treatment centre in Boca Raton that specialised in intractable addicts. I knew that it was the last chance.

A little less than four months later, I was thrown out of Renaissance for having sex with an 18-year-old from Alabama. I was given two bin bags filled with my clothes and told I had 10 minutes to get off the property. I had no money, no credit cards, no place to live. But I'd also been clean for more than three months, and, for the first time since I started using, I felt like I could stay sober. The physical detox- the diarrhoea, the sleeplessness, the anxiety and paranoia - was over, and I was slowly reining in my racing thoughts.

When I had come down to Florida the previous autumn, I'd kept insisting that I'd never live in such a wasteland for more than a month or two. Now that I was out of rehab, I didn't even think of trying to leave. I had learnt some basic survival skills in treatment - how to cook, stick to a budget, pay my bills - but mainly I'd learnt that all I could do to keep from falling over was to keep on walking forward.

The first job I got was as a labourer. I lasted less than a week. I didn't know how to dig a ditch. Next, I landed a gofer gig in a big corporate HQ, but lost this after problems with bus timetables delivered me there an hour late. By this time, I had moved into my own one-room place a block away from the ocean. It could barely fit a queen-sized bed and a TV, and I kept the shade shut and my clothes in a pile in the closet. There was a tiny fridge that could hold either a carton of milk or a bottle of juice, but not both. The previous occupant left her bicycle behind, so now I had a means of transport as well. A friend from rehab got me a job as a busboy in an upmarket restaurant. I had to wear tux shirts and bow ties, and I lived on leftovers.

I still said that I was a writer, even though I didn't have the attention span or discipline even to keep a journal. I told people that before I came to Florida, I'd spent my nights interviewing rock stars. Now, I said, I was about to head off to Cuba on an undercover assignment for Rolling Stone. One day, I was leaning against my bike on Atlantic Avenue, Delray's main strip. A finely muscled pretty boy, who said that he worked in fashion, was introducing himself to a group of us in front of Delray's token café. He was about 10 hours off the plane, and he wouldn't shut up. Fucking punk, I thought. He's finished, he just doesn't know it. He'll never go back to New York, just like that 40-year-old actor will never even audition for the local community theatre. Because they're all too fucking afraid of what it would mean to try and fail. I had written the script to his entire life, when I realised that it was my own.

The next day, I called up the one person I knew who had a computer and printed out a couple of features I'd written years earlier for Addicted to Noise, an early rock'n'roll webzine. I compiled a CV that glossed over the fact that I hadn't held a job in years. And I sent off my sad little packet to the city editors of the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale's daily paper. I figured that I wouldn't get any responses, but at least I had tried. Fred Zipp, the Post's city editor, called me the following week and asked me to come in for an interview.

I dressed in a starched white shirt and black tie and got a haircut. And I got a friend to drive me to the Post's newsroom, an airy, antiseptic place whose over-air-conditioned smell seemed like the most romantic scent in the world. I told Zipp and Tom O'Hara, the Post's managing editor, that I had come down to Florida to visit friends and had fallen in love with the ocean and the weather and the lifestyle. They seemed willing to believe me. Still, this masking-taped explanation didn't cover up the reality that I had no experience working on a daily paper. But for whatever reason, Zipp said that they liked me enough to give me what amounted to a working audition. So, for $1,000 I could work two trial weeks on the metro desk. After that, they'd decide whether to hire me full time. I was surprised to get the offer and tried not to be too hopeful. I told the head waiter at my restaurant that I needed a couple of weeks off but didn't want to give up my shifts.

My first day of work was my 26th birthday, 27 April 1998. I was sent to a local middle school, where Kate Shindle, the reigning Miss America, was speaking. I filed nine stories over the next two weeks - about the World Series of scouting, about a new children's hospital, about the onset of the love-bug season - and then I returned the car that the Post had rented for me, went back to the Hoot, Toot & Whistle, and waited for a call.

One afternoon, it came. Susan Bowles, a gentle woman who was taking over as metro editor, called me. I was at a friend's apartment when I picked up the message, and I curled up on the couch before I called her back.

I have some bad news, Bowles told me. The job we talked to you about has been filled. OK, I thought, still curled up. I still have my job at the restaurant. I can freelance, and eventually I will get a job. But Bowles wasn't done. We really liked you, she said, and we'd like you to work in our South County bureau, covering Boca Raton City Hall. I biked over to the restaurant that afternoon and quit.

I began my job at the Post on 18 May. After briefly trying to convince myself that I could afford a $17,000 Jeep Cherokee, I ended up buying a 1985 Cadillac Eldorado with no silencer, no radio, and questionable brakes. A guy was selling it from his front lawn for $1,000. It was perfect.

Even with a car, I still had trouble passing as a fully engaged member of the real world. Within about a week, the Eldorado's back seat was heaped with papers and magazines and empty fast-food cartons. Since I didn't have a proper fridge, I bought OJ, milk, cereal, plastic bowls and spoons and kept them at the office. I'd get there early every morning and make myself breakfast. I stayed at the office late most nights; I didn't have a computer and had missed years of the internet, so I spent hours surfing.

I did eventually move in to a real apartment and clean up my car. I kept filing stories. I also screwed up the courage to visit New York. And, by 1999, I began looking for other work.

It's easy to obsess about what might have happened when there are only two possible outcomes. But when you're not sure which futures you're choosing between, whichever path you end up on feels inevitable.

About two years ago, I was in Lake Charles, Louisiana on assignment for Newsweek, interviewing the warden at a local jail. "These guys," he said, "were lowlifes. Crackheads who sold their daddy's furniture. Most of them have no future."

He was about to launch into a story about one of them when he stopped himself. "You wouldn't know about any of that," he said. |

| |

|