|

|

|

Editorials | March 2005 Editorials | March 2005

Pipeline From Mexico

Kelly Lecker - The Columbus Dispatch Kelly Lecker - The Columbus Dispatch

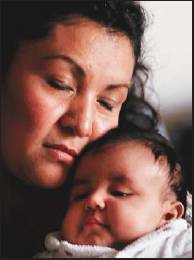

Angelica and Andrea share a quiet moment after dinner.

Baking tortillas in El Paxtle, Mexico, are Angelica’s sister Alicia, left, and her aunt Santos.

Santos rehydrates corn to get it ready for baking the next morning.

Victoria, cousin of Angelica, cradles a Christ child doll during a family celebration of Three Kings Day in Mexico.

An obelisk and a porous fence mark the U.S.-Mexico border, photographed from the American side in southeastern Arizona.

A U.S. Border Patrol officer checks a car headed toward Tucson, Ariz., from Nogales, Ariz., for illegal immigrants.

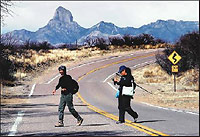

Norma Price, left, and another member of the Samaritans look for Mexican immigrants who have crossed into Arizona. They offer food, clothing and medical care but not housing or transportation.

At home with a Mexican immigrant family: As their sister Citlalli checks herself out in a mirror, Maxly, standing, and Andrea watch television with their mother, Angelica, in their North Side apartment. (Photos: Chris Russell)

|

It’s tough to tell what troubled Angelica more: the news from Mexico that her mom was dying or the agonizing choice it forced her to make. She was pregnant with her second child.

If she traveled back to her tiny hometown, Angelica risked having her baby in central Mexico, denying the child U.S. citizenship and all the security that comes with it. She and her husband Cruz live in the United States, 1,700 miles from their family, largely for those advantages.

If she waited here until she gave birth, Angelica might never see her mother again.

"Cruz asked me what I was going to do," she says. "But it was hard. I hadn’t seen my mom in four years."

Angelica studies her hands as she speaks. She tells this story in the same shy, soft way she tells all her tales of family and the separation that nags at her. The conversation always ends on a high note: Her family has a good life here, she says, almost to herself.

Like countless other Mexican women who have moved to Columbus in recent years to be with their working husbands and other relatives, Angelica, 33, lives in the shadows.

She spends most of her time in her North Side apartment complex, near other Spanish-speaking relatives and friends. She and Cruz have four children now.

Jobs draw thousands of Mexicans to Columbus and other cities where restaurants, landscaping companies, construction crews and others have trouble finding workers for relatively low wages.

Friends and family follow.

Angelica’s oldest brother, Juan, came first. He was working in Chicago when friends told him about better-paying jobs in Columbus. That was a decade ago.

Since then, Angelica, Cruz and three more of her brothers have made their way here. Cousins, nephews and friends followed.

Those connections have opened a pipeline between Columbus and El Paxtle, a farming community of 1,500 in a remote part of central Mexico.

People come north. Money flows back home. Culture streams both ways, changing two places forever.

It happens one person at a time.

New immigrants struggle with separation as they leave behind tightknit Mexican communities.

Angelica knew what she had to do when she heard about her sick mom in 2000.

She took 3-year-old Alex, her first child, and flew with two brothers and a sister-in-law back to El Paxtle.

Two months later, she delivered a daughter, Citlalli, in Mexico.

Angelica’s family wanted her to stay.

"I told them I couldn’t stay. I had a husband back here. I had a life here now," she said.

Without her family, Angelica walked back across the border into the Arizona desert. A car brought her to Columbus. Relatives soon brought her baby — with no legal right to live in the United States. An aunt went back months later to retrieve Alex, now 7, who has papers and can cross legally.

Angelica’s mom died the next year. Only one brother made it from Columbus to Mexico for her funeral.

Angelica can’t imagine when her family will visit El Paxtle again.

"We don’t have papers. That makes it hard. Our kids could go there," she said. Like Alex, 2-year-old Maxly and 4-month-old Andrea were born in the United States.

When they grow up, as U.S. citizens, they will be able to get driver’s licenses and jobs without fear of being picked up and sent to Mexico. And they can travel freely to and from Mexico to see relatives — something that remains a dream for their parents.

It likely will become a dream for their sister, Citlalli.

Because of Angelica’s anguished decision to visit her sick mother, Citlalli, too, will live in the shadows.

A new life

Angelica hadn’t planned to leave Mexico.

She had a full life in El Paxtle, a farming village nestled in mountains about 250 miles northwest of Mexico City in the state of Guanajuato.

Family means everything to Angelica, who has 10 brothers and sisters. Baptisms, weddings and birthdays were good excuses for days filled with cooking and celebration. She cries a little when she remembers how it felt to be part of all that.

A wooden sign on the door of her Mexico home still offers Angelica’s help as a nurse’s aide. She sang in church, helped with local elections.

Then Cruz came home.

He had been in Chicago for five years. As a 17-year-old, he had decided to follow his uncles and his dream of a better life.

Cruz, always quick with a funny story and boisterous laugh, readily embraced American life. He learned English by listening and talking to other workers at the restaurant where he bused tables.

"Most people who come here don’t speak English," he said. "Out of 1,000, maybe 10 are well-educated."

Chicago offered Cruz a steady job and a chance for new experiences. For a young man, living in an apartment with friends and eating frozen dinners was an adventure.

Still, he was homesick. Something was missing.

Back in Mexico, Cruz reunited with Angelica, his childhood friend.

"We grew up together, knew each other as kids. She was the one," Cruz said.

Angelica chimed in quietly: "We would go out. He would have a boyfriend, and I’d have a girlfriend. We were friends."

Cruz flashed a sly smile that filled the space beneath his black-rimmed glasses. "I always knew I was going to marry her."

They married two years later. He was working in construction, but he liked Chicago, where the jobs paid far more than any he could find in Mexico.

In 1997, the couple moved to Chicago. A short time later, their first child, Cruz Alejandro (Alex), was born — the first U.S. citizen in the family.

The culture shock of five years in Chicago took a toll on Angelica. There, she was surrounded by people she couldn’t understand. She didn’t have a job, and she was too uncertain of her English to volunteer anywhere. She missed her family.

"She was unhappy," Cruz said. "In Mexico, she worked. If there was an election like there is here, she’d be working on it. In Chicago, she was lonely."

Two of Angelica’s brothers lived in Columbus. Cruz preferred the big-city life but knew that the only way to make Angelica happy was to give her at least one thing she craved: family.

They moved to Columbus three years ago. "When you’re married," Cruz joked, "you just do what she wants."

Their daily routines in Columbus differ greatly from those of their family in Mexico.

Cruz, 32, is up before 6 a.m. six days a week to get ready for his manufacturing job, his sandwich lunch packed. He deals with traffic like other commuters.

Angelica helps Alex get ready for the school bus. Then she drives Citlalli, the gregarious clown of the family, to preschool, a luxury not offered in El Paxtle. She shops at the nearby Mexican grocery but also enjoys all the choices at a well-stocked Giant Eagle down the road.

The family’s Columbus home is a simple two-bedroom apartment with a large living room and a small, narrow kitchen downstairs.

For the most part, she spends time with other Mexicans. She doesn’t mind the isolation.

"My brother lives right across the yard," she said. "It’s nice having my family close by."

The old life

In El Paxtle, life moves at a slower pace.

At 6 a.m. one January morning, women are bundled up in thick wool coats in a room adjoining the house of Angelica’s older sister, Alicia. They’re pressing corn dough and slapping it onto the flat top of a wood-burning stove, which keeps them warm despite the cold wind blowing through the open door.

Alicia’s aunt takes a break from rolling the dough she made the night before. She pulls 3-foot branches off a pile and shoves them into the stove. Three times a week, the women make tortillas, which they serve with every meal.

The simple, two-story concrete building is home to eight: Alicia, her aunt, father and a brother, plus his wife and three kids. The women wash dishes and clothes in plastic bins outside the bathroom, which is in a small separate building.

Curtains decorated with Christmas poinsettias cover the doorways and sway in the chilly breeze. The thin, iron-trimmed glass doors at some entranceways are open. They don’t do much to keep the cold air out anyway.

Women sweep the dirt paths outside their homes. Behind them, the sun rising over the mountains casts a glow over the town and the farm fields that surround it.

Soon, Angelica’s older brother, Antonio, will leave to walk a mile to his construction job.

Children walk across a 2-foot-deep river on a narrow wooden footbridge to get to the aging, U-shaped school. In summer and fall, the river will be at least 5 feet deep and almost impossible to cross. Until a new bridge is built, that will mean an hour’s walk to town, around the hills.

As long as the river is down, women can walk 10 minutes down a dirt road, across a river and up a dirt path to the center of town to buy groceries or get meat from the small butcher shop operated by the mayor.

They conserve their money for essentials: beans, flour and chorizo, a sausage.

If they need more, they must drive 20 minutes to Silao. Alicia does not have a car, but Antonio can drive her there in the shiny, red Dodge pickup that a brother drove down from Columbus to give him.

The family has a new 17-inch color television, but none of the stations come in well and there is no cable. Instead, Alicia watches videos sent from Columbus. On one warm January afternoon, two years of life in Columbus unfold in her living room.

Angelica’s daughter Maxly is learning to walk. Friends laugh and sing as they mark Christmas, Easter and birthdays. Cruz coos to his new daughter, a niece whom Alicia is seeing for the first time.

It could be years before she sees her beloved relatives in person.

"It can be difficult, very difficult," she said. "I wish they were here, but they need to be there. They’re all there."

Across El Paxtle, men replaster houses, using money they earned at construction or restaurant jobs in Columbus to buy their supplies.

Women all over town have fathers, husbands, sons and brothers living in Columbus.

"In every house, there is somebody who is over there," said Victoria, a cousin of Angelica’s who lived in Columbus and worked at a Mexican restaurant years ago.

Homesick, she moved back to Mexico to be with her mother and other relatives. "There’s a house over there that’s empty because everybody is gone."

A tighter border

If there’s a clog in the pipeline, it’s at the border.

It’s 7 a.m., and the sun is just rising over St. Mark’s Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Ariz. Norma Price is loading food and water into a white Jeep Cherokee.

Price, a retired doctor, and two other women are setting out for the desert, looking for border-crossers who need help. Their group, the Samaritans, hands out food and clothes and treats the injuries, dehydration and illnesses the people suffer while crossing through Arizona. Volunteers do not house or transport illegal crossers.

The desert is littered with water bottles, diapers and clothes left behind by migrants, who walk there every day. Plastic milk jugs — painted brown so they don’t reflect the sun — are halffull of dirty water, likely taken from cattle tanks. The women dump the water so it can’t sicken anyone.

"Hola!" Price shouts into the desert. "Somos amigos! Tenemos agua y comida. Podemos ayudar." Hello! We are friends! We have water and food. We can help.

On this day, nobody answers.

Even in winter, the sun beats down on the desert. Uneven terrain and brush with jagged branches make walking difficult. Migrants sometimes cover 60 miles, walking four days or more, before they reach the place where a car is waiting to take them to their destination.

Sometimes, older migrants are left behind because they can’t keep up, the Samaritans said. Usually, one person stays to help, risking capture by the U.S. Border Patrol and loss of money paid to a smuggler to help them cross.

"They basically risk the $1,500 they paid, just piss it away, to help someone they don’t know," said volunteer Linda Bayless, a nurse. "We call ourselves Samaritans. That is the ultimate good Samaritan."

Stricter enforcement at other parts of the border, especially since the Sept. 11 terrorist attack, has pushed border-crossers into the desert.

Three hundred yards from the border in southwestern Arizona, 70 miles from the Samaritans, Glenn Spencer is looking for migrants, too.

Spencer heads the American Border Patrol, a nonprofit group trying to reduce illegal immigration. The group uses infrared cameras and unmanned airplanes to scan for people crossing over the 4-foot barbed-wire fence that marks the border.

Group members call federal agents and post photos of illegal crossings on their Web site.

"This border can be protected, absolutely," Spencer said. "They just don’t want to do it. They want to keep bad people out and let economic migrants in."

Here, in the middle of a vast expanse of desert, it’s hard to tell that the flimsy fence marks the U.S.-Mexico border. White-and-green U.S. Border Patrol vehicles cruise past, making their rounds and responding to electronic sensors that alert them to crossings.

The night before, migrants drove through the fence in pickup trucks. A neighbor had just finished repairing it.

At official border crossings such as the one in Nogales, Ariz., customs agents search cars for illegal activity. Workers scan passports and compare photos with computer images. They use inspectors, mirrors and dogs.

About 30,000 people a day enter in cars and on foot at this official crossing.

"Our first priority is to prevent terrorism," said Joe Agosttini, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection supervisor. "But we also look for illegal immigrants and drugs. We enforce over 600 laws right here."

More illegal immigrants are caught by the Border Patrol in Arizona than in any other state.

Nationally, 157,000 illegal immigrants were deported in 2003. Many others who were arrested left the country voluntarily.

Immigration officers in Ohio and Michigan removed 1,714 immigrants, including 941 from Mexico, said Rob Baker, head of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention and removal field office in Detroit. His office covers Ohio.

Illegal immigrants arrested for crimes such as drug-trafficking are detained in the roughly 500 jail beds available in Ohio until they are sent home. Because there is so little jail space, many others receive notices to appear in court for a removal hearing.

"About 90 percent fail to show up," Baker said.

He acknowledged that many illegal immigrants in central Ohio face only a slight chance of being deported because there is little money to arrest and remove them. Ohio has some of the most understaffed detention offices in the country, he said.

"It definitely affects the efficiency with which these people are removed," he said. "We have to be honest with ourselves."

In the case of Cruz and Angelica, they entered the United States by squeezing between wires in the fence and walking through a cemetery in Arizona.

"There were a whole group of people," Cruz said. "I told her, ‘Try to keep up. I won’t leave you, but we have to run.’ "

The group listened for border agents and made a run for it. Angelica fell.

"We started at the beginning of the group, then we were in the back," she said.

After two hours of walking, they met a car that took them the rest of their way.

Family members said they paid $800 apiece to smugglers known as coyotes, who helped them cross and arranged for people to pick them up. With border security tighter now, the price has risen to at least $1,500.

Groups on both sides of the immigration issue condemn the smugglers. They say they’ve seen migrants beaten, robbed and nearly killed.

Before the Sept. 11 attack, Angelica’s relatives repeatedly crossed the border, coming to Columbus to work and returning home to Mexico. One brother crossed five times in a decade. That doesn’t happen as much anymore.

Another brother, Antonio, surveys El Paxtle from a tall hill where he has been walking.

"We’ve been lucky. Nobody from here has died. In the next town, there have been people who died."

A big decision

Like most of her relatives and friends in Columbus, Angelica thinks about moving back to Mexico.

But with every passing year, Columbus feels more like home. The powerful combination of jobs, good public schools and available health care — opportunities they lacked in Mexico — tightens its grip on the family.

In the United States, hospitals will treat sick children and allow families to pay the bills when they are able. Mexican hospitals require payment upfront and will refuse even the sickest child, Cruz said.

Alex became ill when Angelica was in Mexico with her mother.

"Then she told them her husband was in the States, and they helped," Cruz said. "That’s the only reason."

Cruz and Angelica realize that they are sacrificing the peaceful farm life and close connections to family in Mexico.

Cruz grabs his 2-year-old daughter in a big bear hug. Half asleep, Maxly snuggles her head under his chin.

"No, we can’t go back," Cruz said. "We have a family to raise here now." |

| |

|