|

|

|

Editorials | June 2005 Editorials | June 2005

The Nation’s All Too Opaque Justice System

Kenneth Emmond - The Herald Mexico Kenneth Emmond - The Herald Mexico

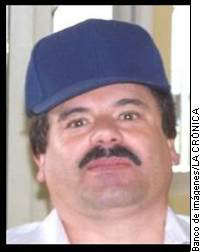

| | The nation's most wanted drug-runner, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. |

Is justice for sale in Mexico? This eternal question resurfaced last Wednesday with a decision to dismiss charges against Ivan Archibaldo Guzmàn, son of the nation's most wanted drug-runner, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Although “El Chapito,” as the younger Guzmán is known, was released on bail, then immediately re-arrested on new charges, the president's office was moved to comment that some judges may be “influenced” by drug criminals. It complained that Mexico can't win the drug war if judges keep letting important suspects go.

The episode prompted the Attorney General's Office to investigate the judge involved, José Luis Gómez of the State of Mexico, for possible links with the Sinaloa drug cartel.

A defiant judge Gómez replied that the charges were dropped because the prosecutors did a sloppy job of preparing evidence.

Well, maybe he's right. How can we know? We weren't invited to hear arguments on the case or see the evidence. There are no details in the written decision to shed light on the judge's thoughts.

It's one of many cases that leave ordinary citizens wondering how Mexico's justice system works, or whether it works at all.

Another involves former Mexico City Mayor Oscar Espinosa Villarreal, recently convicted of embezzling 460 million pesos in the mid-1990s during his stewardship as mayor.

He was sentenced to seven years, six months in prison. He once fled the country and was extradited from Nicaragua to face trial. Yet he's still free, pending who knows how many appeals. If he loses, he'll only have to repay 285 million inflation-diminished pesos. Was that a just decision? We need some guidance to connect those dots.

Contrast Espinosa's situation with the plight of the estimated 80,000 Mexicans in jail awaiting their day in court, in some cases years after they were arrested.

It's natural to ask about courtroom corruption but it's the wrong question. The broad issue concerns the opaqueness of the justice system. Is due process taking place? What is the system hiding? Maybe nothing; we simply don't know.

Yet, in a society with a history of corruption at all levels and legal processes that appear tilted in favor of wealthy defendants, we'd be remiss not to wonder what goes on behind the closed courtroom doors.

What measures would safeguard against judicial corruption or the failure of due process, and gain citizens' confidence that the courts are doing their constitutional duty? There are several.

The process could require defense and prosecuting attorneys to present their cases by verbal debate in court before a presiding judge, instead of through written submissions. The public would be free to witness the trials and all subsequent appeals.

This would be a major step toward fulfilling a basic tenet of a democracy: that justice is done and seen to be done, in contrast to the existing Star Chamber process. Open courts are a powerful disincentive to judges tempted, for any reason, to make unfair or opportunistic decisions.

Judges could be required to issue detailed written decisions. Apart from clarifying the reasoning behind a specific decision, this would provide useful reference points for legal arguments and decisions in subsequent cases, and in appeals.

A third safeguard would be to require judges to submit periodic declarations of their assets and those of their immediate families. Some might argue that this would be an unseemly incursion on privacy, but surely good justice trumps judicial privacy.

Fourth, amparos, or injunctions against imprisonment, should be universal and free. As it is now, the amparo is a privilege restricted to those who have the wherewithal to pay high fees to lawyers, and for all we know in the absence of open amparo hearings, a consideration for the judge.

This would also shift the onus of proof of guilt onto the state, where it belongs in a democracy, and away from the accused, eliminating a major bias against the poor.

Better training for court officers and investigators would reduce the number of “lack of evidence” decisions. Those that are handed down would be more credible because they would be backed by transcripts of courtroom arguments and reasons provided in the written decisions.

Once the justice process is brought into the open and people can see that it's working, the system would be self-reinforcing: judges would gain respect and even prestige when seen as the guardians of due process, instead of being suspected of subverting it.

What chance is there that these reforms could be legislated? Small, perhaps, but the odds are hardly more far-fetched than those for fiscal, energy, or labor reform that are languishing on the president's desk.

Every society must rely on its judges to interpret the laws, and every society has an ongoing concern about whether its judges are competent and honest in the discharge of their duties.

How can we know that those judges are being responsible in their interpretations of the law? Only when citizens are allowed to observe the court system in action can there be any hope of public confidence in the justice system.

It's said that justice is blind. Maybe it is, but that's not a reason why members of society should have to base whatever confidence they can muster for their justice system on blind faith.

Kenneth Emmond is a freelance journalist and economist who has lived in Mexico since 1995. Kemmond00@yahoo.com |

| |

|